Long Teaching Module: “Reading” Primary Sources on the History of Children & Youth

Overview

How do you study the history of young people? What can primary source documents reveal? What limitations do they pose? What light can the history of young people shed on the past? This essay aims to serve as a guide to finding, interpreting or “reading” primary sources on young people from ancient civilizations to the present.

Essay

Introduction

by Miriam Forman-Brunell, University of Missouri-Kansas City

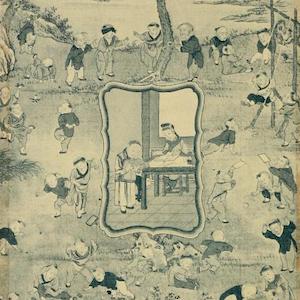

Children spring into view in this 18th-century Japanese ink painting by Hanabusa Itchô. In the painting’s details are seemingly happy children energetically running to see a traveling entertainer’s puppet show. One might assume from this painting, as did Harvard Zoologist Edward Sylvester Morse, that Japan was a children’s "paradise" where babies benefited from riding on the backs of older children instead of crying in their cribs. Yet probing beneath the surface of this source complicates this rosy picture of the past.

A consideration of the age, gender, and class of the children reveal that the half-hidden figures in the window were upper-class girls prevented from playing on the streets. Although the painting portrays the children below as joyful, these komori (babysitters) who provided childcare in exchange for room and board often felt deep despair. While Confucian treatises on education, health, and wet-nursing are sources that reveal nothing about those from the lowest rung of society, other evidence—such as the songs sung by the komori—document more distress than delight.

Knowing how to reexamine established assumptions, consider multiple perspectives, and make connections between inquiry and interpretation is essential to researching the history of children and youth. Critical to that endeavor is the skillful utilization of primary sources (original records created during a period under study or produced by a participant later on) that have survived from the past).

How do you study the history of young people? What can primary source documents reveal? What limitations do they pose? What light can the history of young people shed on the past? This essay aims to serve as a guide to finding, interpreting or “reading” primary sources on young people from ancient civilizations to the present.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

How do I study the history of children and youth?

Start by placing children at the center of inquiry

In standard textbooks on U.S., European, and world history, knowledge about children has been limited to the lives of exceptional youngsters or to anonymous, ordinary children within the family context. Other than a handful of heroes and helpful daughters and sons, children have remained on the margins of historical inquiries that have traditionally focused on adult society. When we place young people at the center of inquiry, we find that they have been an important part of every civilization.

From infancy through childhood and into young adulthood, youth have inhabited huts and houses, orphanages and dormitories. They have worked as domestics, street vendors, slaves, babysitters, and child laborers mining gold in Peru, constructing lanterns in Cairo, and sewing soccer balls in Pakistan. They attended schools and sites of worship where they played, prayed, studied, and socialized.

Children around the world participated in numerous youth organizations such as the Boy Scouts, Girls Scouts, or the Young Pioneers. Some children played visible roles in momentous events and eras in history. At the age of three, Sonam Gyatso became the 3rd Dalai Lama. "Infant rulers" exercised political, military, spiritual, or symbolic power in ancient cultures as well as pre-modern civilizations. Many young people mounted Crusades and sailed on the Mayflower. Still more served on the front lines during the Napoleonic wars and were at the forefront of movements for civil rights and women’s rights.

When we examine the experiences of young people, we often see well-known topics in a new light. And just as often, new topics as well as novel ways of understanding historical shifts and periods come into view. For example, medieval “Dance of Death” woodcuts and murals reveal that panicked parents did not wantonly abandon their children during the Black Death as previously believed. Instead, parents grieved the loss of a child they understood was separated from them by Death.

Use Categories of Analyses

An important initial step toward studying the history of children and youth is to make “age” a category of analysis. Privileging the age of historical subjects is critical because the experiences, opportunities, abilities, expectations, and objects of young people typically differ from those of adults. This Roman marble sarcophagus dating from the first half of the 2nd century, CE, depicts the development of a boy from infancy through childhood.

Yet determining who is a child and who is a young adult is sometimes more challenging than this sarcophagus suggests, as definitions of “childhood” and “youth” have been more fluid than fixed. In addition to actual age, biological maturation has often established the parameters of childhood; yet even the onset of menarche (the age of first menstruation that often signals the beginning of young adulthood), has shifted over time. Since the end of the 19th century, the age at which European girls began to menstruate dropped from around age 16 to about 11 today.

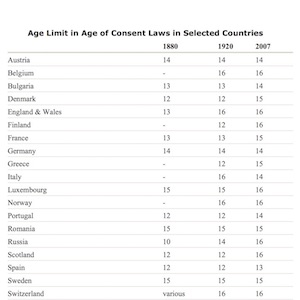

Ideological factors and legal designations that also define childhood have been subject to significant change. While today the average “age of consent” worldwide is 16, a little more than a century ago a child who was 10 or 12 years old was considered legally of age to consent to sexual activity in most American states.

In addition to age, gender is an analytically significant category that is useful for highlighting the different expectations and experiences of girls and boys. Child-rearing customs reliably reveal that the socialization of sons has differed from that of daughters in significant ways. In 16th-century Mexico, for example, a male infant received a shield, arrows, tools, and writing implements whereas a girl acquired domestic objects: a broom, reed basket and spindle.

Also underscoring gender differences are sources that offered child-rearing recommendations to parents as well as those that imparted guidance to children by their parents. According to the observations of a Franciscan friar in his 12-volume manuscript (1569) on Aztec history and culture, indigenous mothers advised their daughters to be neat, speak gently, and walk quietly.

For the most thorough understanding of the identity, circumstances, experiences, and prospects of boys and girls in the past and the present, researchers should consider examining the intersections of age and gender, along with race, ethnicity, sexual identity, and other relevant categories that shape individuals and ideals.

Examine Cultural Constructions

While it is still assumed that “childhood” is universal and unchanging, not all civilizations have shared the same ideas about children. Within every society, ideas about children typically vary over time. In Germany, for example, the effort to redefine childhood as a period of innocence led to the canonization of some folk stories and the elimination of others. A comparison of different editions of Grimm Brothers’ collected works reveals that books published after 1819 omitted troubling stories about children committing senseless acts of violence.

The depictions of children in “classic” works of fiction published between 1865 and 1920 provide another example of older notions of childhood giving way to “modern” ones. Alice in Wonderland (1865), Little Women (1868/9), Tom Sawyer (1876), and many other novels published during the “Golden Age” of Anglo-American children’s literature, reflected the shift in childrearing traditions from didactic literature to entertaining fantasies.

In addition to “childhood,” “girlhood” and “boyhood” are culturally and socially constructed notions inscribed in literary sources, embedded in material culture sources, embodied in art—even engraved on the human body. While activities and exercises coded as male have built up different parts of boys’ bodies than girls’, other cultural traditions have been more invasive. In parts of Asia and Africa where female circumcision has aimed to prepare girls for marriage by eradicating sexual desire and ensuring purity, male ritual circumcision has served to increase their sexual potency and social autonomy.

Despite the prominent differences between girlhood and boyhood, the borders between these constructs have been neither static nor uniform. Folk art paintings, for example, offer visually compelling information that notions of femininity and masculinity have not always been the same. The little boy who donned a fancy dress and delicate pantaloons in this 19th-century painting is at first glance indistinguishable from his older sister. Closer examination of his position, posture, and toys, reveals, however, that while his clothing was feminized, he was practicing the skills and sensibilities—independence, mastery, confidence, control, courage, and dominance—of Victorian masculinity.

Examine the “Lived Experiences” or “Everyday Lives” of Ordinary Children

While idealized depictions of children reveal adults’ expectations of young people, these often did not portray the lives of children as they lived them. The everyday experiences of children were better reflected in other sources, such as documentary photographs. These captured the daily life of Chinese children who sold toys during the 1930s and early 1940s. Artifacts such as birthday hats or “passport masks,” worn by adolescents of the Dan people as they came of age in western Côte d’Ivoire and Liberia, are among the many types of materials that document the numerous rituals and rites of passage ceremonies that have been a part of childhood across all cultures.

While these objects reveal little about how children experienced these events, the diaries and letters children wrote, the games they played, and the school assignments they completed (or did not complete) are some of the many types of documents that can open a window into the subjective experiences of the young.

In countries and cultures where the process of social maturation has been controlled and also contested, documentary evidence can be useful at revealing the methods used by children to “negotiate” between adults’ standards and their own desires. Sources produced by young people along with some created by adults sometimes divulge the ways in which children have sought to comply with adults’ demands and how they challenged them.

Whether in attics or in diaries, children and youth have often defied prevailing dictates by carving out physical or psychological spaces for themselves. In their pursuit of independence children have exhibited historical or social agency in a wide variety of ways.

The everyday activities and as well as “subjectivities” of slave children faced with the competing demands of parents and planters can be gleaned from other kinds of sources: testimonies of fugitives or emancipated slaves, plantation records, folktales, and oral histories. Unlike the interviews conducted by the U.S. Works Projects Administration during the Great Depression, trader inventories or, slave ship logs recorded by captains and their crews, provide numerical information about child enslavement and survival.

Pose Child-Focused Questions

The dynamic process of formulating critical (analytical) questions that will both elicit information as well as inspire more complex questions that ultimately elucidate the relationship between facts and phenomena is central to the enterprise of historical research. Posing specifically child-centered questions makes visible the particular circumstances of children’s experiences that can potentially challenge dominant assumptions. The following are examples of questions that place children at the center of inquiry:

- In what ways do different social arrangements, beliefs, practices, ideologies, and historical forces shape notions of childhood as well as children’s experiences?

- How do race, class, ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexuality, sexual orientation, religion, and region inform childhood, young adulthood, girlhood, and boyhood?

- What evidence is there for multiple notions of childhood, girlhood, and boyhood? Are “dominant” constructs (also referred to as “normative” or “appropriate”) co-existing or contending with subcultural, “non-normative” or “inappropriate” forms?

- What do children and youth think and feel? In what ways do they express themselves?

- How are girls and boys represented, described, and characterized? What kind of rhetorical techniques (e.g., tone, language, metaphors, poses, gazes, imagery) or strategies does the producer employ to convey particular meanings?

How do I use child-related primary sources?

Primary sources provide the raw data out of which the history of girls and boys is reconstructed. Although finding material can sometimes be daunting, a variety of records relating to childhood can be found in archives as well as in attics, on billboards and building walls.

Here are some examples of different kinds of documentary sources used by historians of childhood.

Literary Sources

Literature can provide insight into the history of childhood and youth by revealing how adults’ imagined children and how they addressed them during different historical periods.

From legends to folk tales, picture books to seduction novels, and fiction to biographies, stories aimed at children have often served didactic purposes.

The “Beginner’s Guide,” an educational text from the early Tang Dynasty (618-907), consisted of thrilling stories about famous figures in China’s history and legendary tales. Although Der Struwwelpeter (1845) chronicled the cruel pranks of two boys and the heroics of male leaders, it also served a pedagogical purpose. From the “bad” boys, German children learned about the importance of duty, discipline, and obedience.

Fiction is just one kind of literary source; others include children’s periodicals, school or children’s newspapers, such as New Zealand’s The School Journal. American school children first began reading versions of My Weekly Reader in the early 1900s. Its many poems, jokes, songs, rhymes, articles, and letters to the editors enable researchers to piece together the cultural concerns of adults as well as the cultural worlds of children.

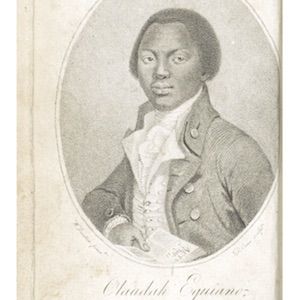

Unique among literary sources are slave narratives that provide insight into children’s impressions, thoughts, experiences, and feelings. In his 1789 narrative, Olaudah Equiano recalled the slave raids he witnessed first hand at age 11. One-quarter of all slaves who crossed the Atlantic were children like him and Ottobah Cugoano whose 1787 memoir also described the differential treatment of children during the Middle Passage.

Harriet A. Jacob’s Incidents in the Life of Slave Girl Captivity (1861) provides insight into the specifically gendered experiences of girls on plantations. Captivity narratives (such as Mary Jemison’s 1824 recollection of her abduction by the Seneca Indians), autobiographies, memoirs, and testimonies (such as those of Holocaust victims) can provide an explicitly child-centered perspective of events as well as self-reflections formed later in life.

Personal Texts

Sharing similarities with narratives and memoirs are letters, diaries, and accounts that reveal thoughts and feelings that were personal but not necessarily “private.” Not only did letters and diaries historically include a broad audience (e.g., family members), but they were also shaped by cultural conventions in both form and content. That is the case among seemingly private missives as well as the many letters sent to Santa that often reveal the desires of young consumers.

Legal Documents

Legislation, ordinances, acts, statutes, handbills, and other official documents produced by governments, courts, and international bodies (e.g., United Nations) are among the many kinds that can be used to research children’s history. For example, historians have concluded that 70 percent of those indicted under the Infanticide Act of 1624 were servant girls under the age of 16.

Girls’ voices can better be heard in the official records of witchcraft trials that spanned 200 years of European and American history. Whether they were accused of witchcraft or blamed others for their bewitching, children’s testimonies shed light on their position within families, their role within communities, and the uncertainties of everyday life that fueled fears about the supernatural.

Institutional Records

Institutional records produced by the multitude of private and public agencies established for the care, education, training, and confinement of boys and girls are a key source of information about young people. One problem, however, is that official reports written by administrators of educational institutions and organizations for children typically represent an institutional view rather than the perspective of youthful insiders.

Nevertheless, institutional records are valuable. Records from 19th-century lunatic asylums, for example, provide an understanding of the historical construction of “feeblemindedness.” Moreover, the uniformity of institutional record keeping is ideal for quantitative methods of research.

Contracts to adopt orphans or other legal agreements that led to the employment of child apprentices are notarial documents that provide information about the adoption practices and the employment of abandoned children. Orphanage records detail the scores of poor children who lived at the margins of society in France, Portugal, the U.S., and elsewhere in the world. Written records can be advantageously supplemented by photographs such as those that document the establishment of Indian mission schools.

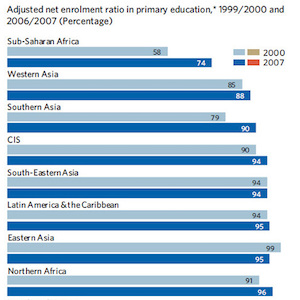

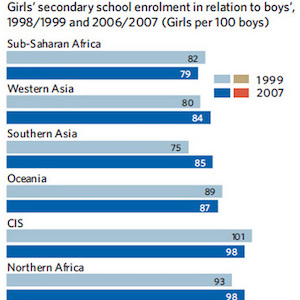

Tables and Charts

Tables and charts that draw upon a variety of historical and/or contemporary primary sources provide researchers with data expressed as a measurable quantity. These “quantitative” formats also provide comparative contexts. A table on “age of consent” laws, for example, reveals that definitions of childhood shifted across time and spaces.

The many charts and tables compiled under the auspices of the UN Millennium Development Summit provide information on worldwide childhood poverty, hunger, education (primary through higher education), gender equality, and health (malnutrition).

Material Culture Sources

Material culture (or objects) from the past can provide other kinds of information unavailable elsewhere. Historians can obtain information about adults’ ideals, children’s practices, social relations, and the meanings of things by “reading” or interpreting the ideas encoded in art and artifacts.

Tombstone inscriptions and symbols as well as burial sites, like the ruins of a cemetery for infants in the North African city of Carthage, can be "read" for the knowledge they provide about childhood as well as parental grief.

In ancient Rome, funeral commemorations included epitaphs and life-stage depictions of children eating food, playing with toys, and learning with scrolls. Archeological findings of mummified children reveal the nature of sacrificial methods as well as the meanings of child sacrifice among the Incans.

Food-related objects, such as an ancient Phoenician baby bottle and bread molds, are material culture sources. These along with food advertisements and other visual and textual sources can provide an understanding of children’s health, experts’ advice, parents’ practices, and children’s preferences.

Evidence of childhood can be found encrusted in archeological finds, documented in patents of inventions, and represented in art and architecture. Toys from dolls to dice furnish facts about the principles, methods, and meanings of play.

In addition, artifacts of clothing, paintings, sculptures, architecture, and photographs can convey supplementary information about the well-being of children. Diapers might cover babies’ bottoms, but interpreting these water resistant receptacles made out of cotton, moss, or other absorbent materials can uncover adults’ expectations of children’s bodily control and mobility.

Visual and Representational Sources

Images of boys and girls can be found in paintings, prints, photographs, advertisements, billboards, murals, posters, as well as movies, cartoons, videos, and other visual sources created by adults, adolescents, and children. Many images are visual prescriptions of what children should do and proscriptions about what they should not.

The Codex Mendoza, a mid 16th-century historical account of the Spanish conquests of Mexica (Aztec) includes representations of indigenous children from infancy to adolescence that reveal examples of gendered- and age-specific norms, transgressions, and punishments.

Although realistic representations of children are harder to come by than idealized ones, some paintings and photographs (especially candid and documentary images) can display more accurate characterizations of childhood than other visual forms. It is important to understand that while a primary source might appear to provide an accurate portrayal, even documentary photographs can be carefully staged.

Jacob Riis’ bleak photographs of Progressive Era immigrant babies, boys, and girls living in wretched urban conditions sought to capture the attention and evoke the sympathy and charity of middle-class Americans.

Many objects of art created by children have not survived, of course, but those that have include embroidered samplers and needlework pieces passed down through generations. Anne Green’s needlepoint of Liberty in the Form of the Goddess of Youth is an exceptional example of schoolgirl art that seamlessly intertwined newly constructed notions of feminine and national identity.

In order to understand the concerns of youth, some historians have examined cultural productions not directed by adults. The “tags” and “throws” of graffiti art or stenciled images on city walls provide a visual record of the concerns and conversations of urban youth.

Audio and Audio/Visual Sources

Also helpful for research are songs that yield understandings of the topics, themes, and concerns of children—and about them. Evocative song lyrics, such as "I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier," are printed on sheet music, in song books, and other published works.

Fortunately for researchers of children’s culture, Isaac Taylor Headland (1859-1942), a resident of Beijing and a scholar at Peking (Beijing) University, collected turn-of-the-century nursery rhymes from the nurse-maids he interviewed as well as from children who sang in the streets and neighborhoods of Beijing and the surrounding region in 1900.

Although less abundant, there are actual recordings of songs—those about children, sung to children (e.g., lullabies), and others sung by children. Aspects of children’s folk culture, particularly playground, counting, camp, and school songs as well as jump rope rhymes and scouting chants have been passed down through the generations. There are a number that can also be found on audio recordings.

Caribbean, Songs and Games for Children and Children’s Songs from Kenya are some of those in the vast collection of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings that document, preserve, and disseminate sound. Included on one recording is an example of the subversive folklore of childhood. Deliberately disgusting versions of “Great Green G(l)obs of Greasy, Grimy Gopher Guts,” have been sung by generations of American school children since the postwar era.

Parodic songs that draw upon the shared meanings of children’s culture often appropriate familiar tunes, as “Batman smells,” an intentionally crude song sung to the tune of the Christmas classic, “Jingle Bells.”

Other audible sources include interviews and oral histories. New Zealanders interviewed by The Colonial Childhoods Oral History Project (CCOHP) narrate recollections of their early years by covering a wide range of topics from chores to church and food to friends.

Video documentaries that combine sound recordings with moving images of interviewees provide researchers with a more complete picture of the past. For example, in one video documentary, former students of Howard High School candidly discussed the challenges they faced and the benefits they received while attending the only free black high school in Delaware until the 1950s.

How do I interpret or "read" primary sources?

Identify

A first reading of a documentary source is not always accurate; a closer re-reading can reveal underlying values such as those in prescriptive sources that aim to establish or reinforce acceptable standards, ideas, attitudes, beliefs, and practices. (Proscriptive sources prohibit departures from established norms.)

Discursive sources establish perceived truths (e.g., about African American slave children as ignorant) and legitimatize unequal power relations (such as those between whites and slaves).

Although descriptive sources by nature “describe” an occurrence, thought, or emotion, they are not necessarily free of bias.

Interrogate

In order to achieve an understanding of the past that is as precise as possible, researchers interrogate or “unpack” original sources by cautiously, critically, and actively posing questions about authorship, audience, content, context, purpose, uses, reliability, and meanings.

Scholars have been able to uncover significant data about the origins, uses, and meanings of specific sources of evidence by subjecting them to a systematic method of inquiry. Different kinds of documents often demand specific analytic techniques, yet all require a scholarly approach that is skeptical and critical. Whether investigating texts or objects written by adults or created by children, consider posing probing questions such as:

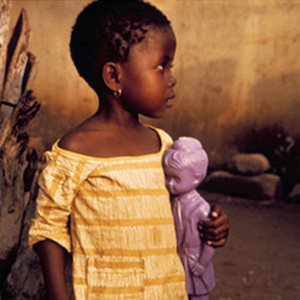

- What kind of primary source is it? A toy for kids? An icon for adults? Or does it serve a variety of purposes as have dolls in the countries of Burkina Faso and Ghana in West Africa?

- Who created the source? In what ways did the age, sex, status, etc. of the creator shape the creation of the source?

- Where was it created? Produced? Found?

- When was the source created? Published? Produced?

- Under what conditions was it created?

- Why was the source created, invented, or produced? Depictions of happy babies, earnest children, and industrious youth in Soviet and Chinese poster art aimed to socialize, educate, amuse, persuade, and control.

- What is the point of view of the producer of the source? What textual or visual vocabularies were utilized that indirectly communicated biases or reinforced beliefs? What were the unspoken assumptions encoded or embodied in it?

- Who was the source created for? Who used it?

- What did the source mean to children and/or adults? How did they interact with it?

- What were the larger historical contexts (e.g., concepts of childhood) at the time of the source’s creation?

Corroborate

Primary sources are fundamental to understanding the past yet they do not provide an unmediated view of history. At best, by themselves they can only provide a partial view. Inherent to most primary sources are inaccuracies, uncertainties, and ambiguities. Secondary sources—books and articles written by scholars—can corroborate research findings, clarify ambiguities, provide constructive context, or perpetuate historical inaccuracies. Expanding frameworks that deepen your understandings of the broader milieu can also produce more connections between the history of children, larger social trends, and your particular subject of study.

By comparing primary sources, one can ascertain the veracity of an account and determine whether it is representative, remarkable, or realistic. Over the course of a little more than a century, the original 16th-century watercolor of a Native-American girl was transformed into that of a boy in subsequent publications about youthful New World inhabitants.

When faced with conflicting evidence, comparing sources might strengthen the evidence, provide additional information, and resolve disparities. A memoir, diary, or a letter, for example, could provide information missing from a photograph. Thinking about the possible explanations for the disparities you encounter while re-reading sources is likely to lead to new questions, revised assumptions, and new avenues of inquiry. This dynamic process of historical inquiry—reformulating questions, assumptions, and methods—typically leads to clearer understandings and innovative interpretations.

Whether analyzing police reports, children’s poems, or parents’ wills, historians pay particular attention to the uses of language in order to decipher meanings of symbolic systems from “bureaucratese” to baby talk. The skill of interpreting the language and tone of documents from earlier periods is key to understanding the assumptions and sensibilities of people in the past.

Compare

Comparative approaches can bring significant aspects of childhood to light. For example, a comparative study of the coerced migrations of children (e.g., orphans, Jews, Africans, and the poor) makes plain the similarity in cultural forms and childhood ideals that overlapped national boundaries.

A comparison of Pieter Bruegel’s Early Modern European painting, “Children’s Games,” with illustrations of girls’ and boys’ games and toys in woodblock prints or ukiyo-e from the Tokugawa period (1600–1868) exhibits the similarities and differences in children’s play activities in two countries over two centuries.

Sometimes single sources, such as the Narrative of Life of Frederick Douglass (1845), are particularly advantageous to comparative analyses. Douglass’ descriptions of slave boys with girls, the free with the unfree, children with adults, and urban with rural slaves lays bare the roles that gender, status, age, and region played in shaping childhood in the 19th-century South.

What are the limitations of source material?

While primary sources can provide a window into the past, the view is typically more partial than complete. Interpretive challenges are frequently posed by the extant evidence whether or not there is a lot or very little of it. Rarely, if ever, is surviving information wholly reliable at revealing an accurate and complete picture of the past.

The perspective of most primary sources is inherently biased. Whether deliberately or not, documents reflect the point of view of the people who created them. For example, while the painfully slow process of having ones picture taken made many Victorian children miserable, the somber expressions captured on daguerreotypes also reflected studio photographic conventions, gender ideals, class distinctions, and age hierarchies. They also captured racial codes, and diminished ethnic cultures, and cloaked sexual orientations.

Recollections of childhood and young adulthood recorded in memoirs, autobiographies, and other "life writings" (including oral history interviews) raise other evidentiary issues. Memories called to mind long after they occurred are filtered by age, anxiety, or subsequent events. For example, a half-century after the Massai murran youth rioted against British colonial rule, their recollections of events blended distant memories of adolescence with the mature perspective of their current position as community elders.

And while a poor memory might lead to inaccurate recollections, a nostalgic longing for halcyon days might generate a romanticized reminiscence. Drawing upon the recollections of family or community members who have embroidered the past might also contribute to apocryphal tales that contain more fiction than fact.

If a source was produced by parents, teachers, experts, or authors, it is likely to shed light on adults’ expectations and perceptions of young people. Documents produced by prisons, for example, typically represent the point of view of disciplinarians rather than those of youthful inmates. Sometimes reading against the grain of adult-generated sources can yield surprising results about young people. In addition, "alternative readings" of cultural products (like books) by young people can shed new light on youthful challenges to adult standards.

A source produced by a young person is very likely to reveal youthful cultural values, beliefs, behaviors, practices, and perspectives. A petition submitted by teenagers to the U.S. Secretary of Labor imploring him to allow the Beatles to enter the country in 1964 shows the emergence of American teenage subcultural principles, politics, and practices.

Why study the history of children and youth?

Although the fields are relatively new, the history of childhood, youth, and girls’ studies have already brought into sharp focus the innumerable ways in which young people since the earliest cave dwellers have left marks on societies and civilizations. While most sources make known adults’ attitudes about children, others give voice to girls’ and boys’ thoughts and feelings.

Whether examining culturally constituted ideas about childhood or the everyday experiences of the young, your research has the potential to produce original insights and even to create new areas of historical inquiry. By interpreting the rich record of young people, your research in the present will contribute to a more accurate understanding of our past.

Credits

MIRIAM FORMAN-BRUNELL (Project Co-Director) is a Professor of History at the University of Missouri-Kansas and a leading scholar on the history of American children. Dr. Forman-Brunell is the author of Made to Play House: Dolls and the Commercialization of American Girlhood, 1830–1930 (1993;1998) and Babysitter: An American History (2009). She is also editor of Girlhood in America, An Encyclopedia (2001); The Story of Rose O’Neill (1997); co-editor (with Leslie Paris) of The Girls’ History & Culture Reader (2010), and series book editor of Children and Youth: History and Culture (2003–08).