Long Teaching Module: Sexuality, Marriage, and Age of Consent Laws, 1700-2000

Overview

In western law, the age of consent is the age at which an individual is treated as capable of consenting to sexual activity. Consequently, any one who has sex with an underage individual, regardless of the circumstances, is guilty of a crime. Narrowly concerned with sexual violence, and with girls, originally, since the 19th century the age of consent has occupied a central place in debates over the nature of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, and been drawn into campaigns against prostitution and child marriage, struggles to achieve gender and sexual equality, and the response to teenage pregnancy. This module traces the shifting ways that the law has been defined, debated and deployed worldwide and from the Middle Ages to the present. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, potential adaptations, and essay prompts relating to the twelve primary sources.

Essay

Introduction

In western law, the age of consent is the age at which an individual is treated as capable of consenting to sexual activity. Consequently, any one who has sex with an underage individual, regardless of the circumstances, is guilty of a crime. Narrowly concerned with sexual violence, and with girls, originally, since the 19th century the age of consent has occupied a central place in debates over the nature of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood, and been drawn into campaigns against prostitution and child marriage, struggles to achieve gender and sexual equality, and the response to teenage pregnancy. This module traces the shifting ways that the law has been defined, debated and deployed worldwide and from the Middle Ages to the present.

An age of consent statute first appeared in secular law in 1275 in England as part of the rape law. The statute, Westminster 1, made it a misdemeanor to "ravish" a "maiden within age," whether with or without her consent. The phrase "within age" was interpreted by jurist Sir Edward Coke as meaning the age of marriage, which at the time was 12 years of age.

A 1576 law making it a felony to "unlawfully and carnally know and abuse any woman child under the age of 10 years" was generally interpreted as creating more severe punishments when girls were under 10 years old while retaining the lesser punishment for acts with 10- and 11-year-old girls. Jurist Sir Matthew Hale argued that the age of consent applied to 10- and 11-year-old girls, but most of England's North American colonies adopted the younger age. A small group of Italian and German states that introduced an age of consent in the 16th century also employed 12 years.

An underage girl did not have to physically struggle and resist to the limit of her capacity in order to convince a court of her lack of consent to a sexual act, as older females did; in other words, the age of consent made it easier to prosecute a man who sexually assaulted an underage girl. However, since the age of consent applied in all circumstances, not just in physical assaults, the law also made it impossible for an underage female to consent to sexual activity. There was one exception: a man's acts with his wife, to which rape law, and hence the age of consent, did not apply.

In trials, juries were often unwilling to simply enforce the law. Rather than focusing strictly on age, they made judgments about whether the appearance and behavior of a girl fit their notions of a child and a victim. It was not only that relying solely on age seemed arbitrary to them; at least until the end of the 19th century, age had limited salience in other aspects of daily life. Laws and regulations based on age were uncommon until the 19th century, and consequently so was possession of proof of age or even knowledge of a precise date of birth.

Near the end of the 18th century, other European nations began to enact age of consent laws. The broad context for that change was the emergence of an Enlightenment concept of childhood focused on development and growth. This notion cast children as more distinct in nature from adults than previously imagined, and as particularly vulnerable to harm in the years around puberty. The French Napoleonic code provided the legal context in 1791 when it established an age of consent of 11 years. The age of consent, which applied to boys as well as girls, was increased to 13 years in 1863.

Like France, many other countries, increased the age of consent to 13 in the 19th century. Nations, such as Portugal, Spain, Denmark and the Swiss cantons, that adopted or mirrored the Napoleonic code likewise initially set the age of consent at 10-12 years and then raised it to between 13 and 16 years in the second half of the 19th century. In 1875, England raised the age to 13 years; an act of sexual intercourse with a girl younger than 13 was a felony. In the U.S., each state determined its own criminal law and age of consent ranged from 10 to 12 years of age. U.S. laws did not change in the wake of England's shift. Nor did Anglo-American law apply to boys.

Behind the inconsistency of these different laws was the lack of an obvious age to incorporate into law. Although scientists and physicians had established that menstruation and puberty occurred on average around age 14 in Europe at this time, different individuals experienced it at different ages -- a fluid situation at odds with the arbitrary line drawn by whatever age was incorporated into law.

At the end of 19th century, moral reformers drew the age of consent into campaigns against prostitution. Revelations of child prostitution were central to those campaigns, a situation that resulted, reformers argued, from men taking advantage of the innocence of girls just over the age of consent. W. T. Stead's series of articles entitled, "The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon," published in the Pall Mall Gazette in 1885, was the most sensational and influential of these exposés.

The outcry it provoked pushed British legislators to raise the age of consent to 16 years, and stirred reformers in the U.S, such as the Women's Christian Temperance Union, the British Empire, and Europe to push for similar legislation. By 1920, Anglo-American legislators had responded by increasing the age of consent to 16 years, and even as high as 18 years.

While those ages were well beyond the normal age of menstruation, proponents justified them on scientific grounds that psychological maturity came later than physiological maturity. They also argued that the age of consent should be aligned with other benchmarks of development, such as the age at which girls could enter into contracts and hold property rights, typically 21 years. Opponents remained focused on physiological maturity, however, and argued that girls in their teens were sufficiently developed not to need legal protection. Moreover, they argued, by late adolescence girls possessed sufficient understanding about how to use the law to blackmail unwary men.

Historians have argued that increasing the age of consent also gave the law a more pronounced regulatory dimension. In practice, these laws were often used to control the behavior of the working-class girls. Yet reformers at the time saw no distinction between protection and regulation: in making it a crime for girls to decide to have sexual intercourse outside marriage, the law protected them from themselves and from the immature understanding that led them to behaviors reformers considered immoral.

In addition to class, the intersection of race and age also gave the law a regulatory character. In India, for example, the prevalence of the custom of child marriage among Hindus led the British colonial authorities to apply the age of consent to married as well as unmarried girls, thereby creating a crime of marital rape that did not exist in British law. The 1860 Indian Penal Code set the age at 10 years; in 1891 the age of consent but not the age of marriage was raised to 12 years. As a result, the age of consent regulated the consummation of marriage, ensuring that it was delayed until an age when Indian girls were considered likely to have begun menstruating.

A furious debate preceded the enactment of the 1891 law, focused in large part on whether the law violated the commitment the British government had made in 1857 not to interfere in native cultures. That Indian law set the age lower than British law reflected ideas that non-white races "matured earlier," in part because of the environments in which they originated. In the U.S., those who opposed resetting the age of consent to 16 made similar arguments about African-Americans, Mexicans, and Italian immigrants. Australian legislators even claimed that white girls living in sub-tropical climates "ripened" into women earlier than those in Europe.

The behavior of underage girls gave support to both proponents and opponents of the increased age of consent. Increasingly living in cities and working in factories, offices and stores, working-class girls with a new freedom from the supervision of family members and neighbors cultivated a flamboyant, sexually expressive style that extended to consensual sexual activity, usually with men only a few years their elders. Their new freedom brought girls danger as well as pleasure: subordination at work and dependence on men for access to leisure, limited their agency and ability to consent, and sometimes exposed them to sexual violence. Girls involved in age of consent prosecutions came in roughly equal numbers from each of those groups.

In the 1930s, support for setting the age of consent at 16 years or older began to weaken. Characterized by growing economic, social, and cultural independence, girls in their teens assumed a place in western societies quite distinct from that of younger children. New concepts of adolescence and specifically of girlhood normalized sexual activity during the teenage years, at least within peer groups, as "sex play" necessary to achieve adult heterosexuality. Emboldened and influenced by such ideas, girls more often talked of being "in love" with the men charged with having sex with them, and expressed sexual desire. Prosecutors and juries increasingly refused to treat such cases as rape.

Legislators, however, did not reduce the legal age of consent. The resulting tension was reflected in slang, most notably the American term "jailbait," dating from the 1930s, that registered cultural recognition of teenage girls as sexually attractive, even sexually active, but legally unavailable. American legislators did amend laws to take account of the offender's age during the 1940s and 1950s as teen culture expanded and female adolescents exercised their sexual autonomy. During and after World War II, if both the male and female were underage (or between two and six years above the age of consent), the punishment was reduced.

By the 1970s, feminist rape law reform campaigns had helped to expand age of consent laws. Aiming to challenge stereotypes of female passivity and growing concern about male victimization, they made it clearer that the laws concerned all youth—male and female—and that the laws protected them from exploitation rather than ensuring their virginity. European nations in general did not follow suit. Only Britain, in 2003, revised its legislation, making an act committed by an individual under 18 with one under 16 a separate, lesser offense.

A more broadly adopted element of feminist rape law reform was the application of gender-neutral language: instead of referring to "females" the law referred to any "person." Unchanged, however, was the nature of the act addressed. Age of consent laws applied only to heterosexual intercourse. The new language criminalized acts between underage boys and women, but not those between boys and men. Promoted as a means of formalizing equality between men and women, gender-neutral language won support as a means of protecting boys. The treatment of such cases, however, was not gender neutral and drew upon gender stereotypes. In practice, boys were imagined as sexual agents, not victims, and as sexual agents, the prevailing assumption was that they would not be harmed by sexual acts with adult women.

In the U.S., the Supreme Court ruled that it was constitutional to apply the age of consent only to girls. The ruling found a new, "modern" basis for the law: the consequences of pregnancy for females. Although out of line with a broad shift toward formal legal equality between males and females, the decision fit the circumstances of the small number of cases still being prosecuted. And despite this ruling, gender-neutral laws were still enacted around the country.

This debate foreshadowed a new link between the law and teenage pregnancy in the 1990s. Conservatives seeking to control adolescent sexuality joined with welfare reform activists. They promoted claims that the enforcement of the age of consent could prevent teenage motherhood (and rising welfare costs) that resulted from girls' exploitation by adult men. Few cases actually fit that pattern, but campaigns to publicize and enforce the law on that basis were implemented in at least 10 states.

At the end of the 20th century, outside the U.S., age of consent laws were expanded to include same-sex acts, due in part to growing tolerance of homosexuality and desire to reach those at risk of AIDS. In the first half of the 20th century, all the European nations, other than Italy and Turkey, that had followed the Napoleonic code in treating heterosexual and homosexual acts alike had recriminalized homosexual acts, either establishing a total ban or an age of consent higher than that for heterosexual acts. In the last quarter of the century, arguments that boys developed later and needed to be older to appreciate the social consequences of homosexual acts began to fade.

European nations began establishing a uniform age of consent for heterosexual and homosexual acts in the 1970s. Under pressure from the European Commission on Human Rights, the former Soviet states and the United Kingdom were the last to revise their legislation at the beginning of the 21st century. In 2003, New South Wales became the final Australian state to adopt a uniform law. In that same year, a U.S. Supreme Court decision decriminalized consensual sodomy, opening the way for the invalidation of unequal laws, a process started in 2005. As of 2007, Canada, Cyprus, and the British territories of Gibraltar and Guernsey were the only western nations without a uniform age of consent for heterosexual and homosexual acts.

More than 800 years after the first recorded age of consent laws, the one constant is the lack of consistency. Laws around the world define the socially appropriate age of consent anywhere from 13 to 18. Some differentiate between heterosexual and homosexual acts while others do not. Some apply to young men as well as young women and others remained focused on the lives and actions of girls. And beyond the legislation lies the world of practice, an even more complex story.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

The primary sources in this module have been chosen to highlight the shifting ways that age of consent laws have been defined, debated and deployed in Western nations over time. To make sense of these documents, it is important to recognize the historically contingent nature of childhood and girlhood: the answer to who is a child or girl differs depending upon the historical period. Bodies are perceived differently and are different to the extent that the average age of puberty has fallen; psychological development and understanding are not always important in definitions of childhood.

It is also important to recognize two tensions within age of consent laws. First, the arbitrary nature of the legal category of age was at odds with fluidity of growth: while the law treated all underage girls as equally mature (or immature), in practice judges and juries confronted the fact that they were not. Second, the age of consent had a dual nature, both protective, in the sense that it removed the need for a girl to show resistance to charge rape, and regulatory, in that it precluded an underage girl from consenting. Broader questions about the law also underpin the issue of the age of consent. Can the law change people's ideas? Can the law stop individuals from having sex? What role do unenforced laws play in shaping cultural attitudes and social behavior?

These sources track the shifting meanings of the age of consent. The Arrowsmith trial demonstrates its role in rape law and the gap between the statute and legal practice. The "Maiden Tribute" articles connect rape and prostitution, making clear how the age of consent became part of anti-prostitution campaigns. The WCTU petition also refers to sexual assault, but incorporates circumstances in which girls consent to their own ruin, highlighting the new regulatory arguments for the law that came to dominate campaigns to increase the age.

Yajnik's speech links the age of consent and marriage and shows the different forms regulatory arguments could take in colonial contexts. Texas legislators' grounds for opposing an increased age highlight the divergent understandings of childhood that existed even when the age of consent was being raised. Morris Ploscowe's later commentary on the law in many ways echoes those arguments, but does so within a new framework, the modern concept of adolescence, that provides them with expert backing. The notion of jailbait invoked by Andre Williams' song speaks to a recognition in popular culture of the same tensions between the sexualization of adolescents and existence of the law that Ploscowe identifies.

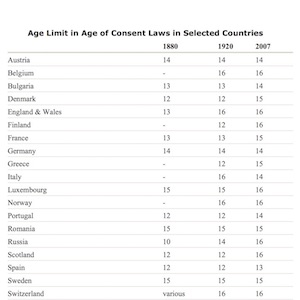

Against the backdrop of these tensions, the U.S. Supreme Court decision again shifts the grounds for the age of consent, this time to the consequences of sex for girls;specifically pregnancy. The Virginia billboard builds on that argument, linking the age of consent to public health and positioning the law as a means of changing behavior. The table of ages used in western laws highlights the historical and contemporary variations in age of consent laws, and the comparatively higher ages employed in the Anglo-American laws relative to Europe. Finally, the decision in the Sutherland case highlights a further shift in the meaning of the age of consent, to encompass in not only boys, but also same-sex acts.

Discussion Questions

- What justifications for the age of consent do different sources offer? What arguments against the age of consent, or for a lower age of consent, do different sources offer? What do those arguments suggest about why the age of consent has increased since the 19th century? What do those arguments suggest about why there is so much variation in the age used in the laws of different nations? What is the relationship between age of consent laws and changing notions of girlhood and adolescence?

- What issues have been connected to age of consent laws in these documents? What was the basis of those connections?

- Does the age of consent primarily protect or regulate children, especially girls', sexuality? Is the answer different at different historical moments or in different cultures?

- Why did the age of consent not apply to boys in Anglo-American cultures until the 1970s? Why did it not apply to same-sex acts in those cultures until the 1960s, and not at an equal age until 2000? Is the age of consent still gendered? Does it still apply primarily to girls?

Lesson Plan

Time Estimated: two 45-minute classes

Objectives

- Describe and analyze changes and continuities in Western childhood during the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Define "age of consent" and analyze age of consent laws to see continuity and change over time in dealing with age, gender, and context.

- Analyze point and view and purpose of historical documents, including audience, author, place, and time period.

- Compare laws to other sources (including articles, commentaries, and speeches) to analyze changing definitions of childhood over time and place.

- Analyze the influence of Enlightenment and other ideologies on age of consent laws.

- Discuss how historians study and find evidence of the developing concept of childhood.

Materials

- Sufficient copies of sources:

The Trial of Stephen Arrowsmith

"The Violation of Virgins"

Petition to Raise the Age of Consent

"Review of the Age-of-Consent Legislation in Texas"

Adolescent Sexual Experimentation Should Not Be a Crime

Jailbait

U.S. Supreme Court Decision Justifying Gender-Based Age of Consent Laws - Copies of the "Childhood in Medieval England" article

- Copies of the "Age of Menarche in Norway" chart

- Copies of the APPARTS worksheet

- Poster paper, magic markers

Day One

Hook (10 minutes)

To get the students thinking about what childhood means, have them write a short description of their daily lives when they were eight. Then, have them share their descriptions with each other in groups of two or three.

In-class Reading (25 minutes)

Explain to the students that they will be comparing their childhood to children's lives in medieval England. Have the students read the "Childhood in Medieval England" article, either individually or in pairs. Then, ask the students the following questions:

- How was children's work life similar and different from today's?

- How was children's leisure time similar to and different from today's?

- In general, how were people's understanding of the boundary between childhood and adulthood similar to and different from our understanding of that boundary today?

Lecture (10 minutes)

Give students a brief lecture to provide them with a basic understanding of age of consent laws: what they are, why they were made, and how they can indirectly define childhood by setting a boundary between childhood and adulthood. The purpose of the lecture is to prepare the students to read the introductory article at home before the next class; the first paragraph of the article is a good source for this lecture.

Homework

Assign students background reading from the introductory article. You may also wish to have them respond in two to three paragraphs to the following prompt: "What should the age of consent be in America, today? Defend your answer, citing at least three issues discussed in the reading."

Day Two

Share (5 minutes)

Have students share the specific age they selected, as well as their findings on historical age of consent laws from the reading.

Small-Group Work (30 minutes)

This activity helps students further understand the various issues around age of consent laws, as well as give them a chance to practice their document analysis skills. Break up the class into groups of two to three students. Assign half of the student groups all three documents from group A (below) and the remaining student groups all three documents from group B.

- Group A

Source 2: "The Violation of Virgins" Newspaper Article

Source 7: U.S. Supreme Court Decision Justifying Gender-Based Age of Consent Laws Legal Document

Source 9: "Isn't she a little young?" Billboard - Group B

Source 3: Petition to Raise the Age of Consent

Source 5: Increased Age of Consent Speech

Source 6: Adolescent Sexual Experimentation Should Not Be a Crime Commentary

Have the students analyze their sources to find the point of view and purpose in each source. The students then should identify how the sources show a continuity or change in the age of consent law for that country, region, or colony. Each group should fill out an APPARTS worksheet for each document as part of this analysis. Then, have each group jigsaw share their findings with a group that analyzed the other set of documents to share their findings with each other.

Lecture/discussion (10 minutes)

To help students understand how the Enlightenment influenced these changes, have the students read this short excerpt from Rousseau's Emile, or read it to them aloud (along with the background information). In a short discussion, have them explain how these Enlightenment ideas might relate to changes in age of consent laws.

Day Three (Optional Activities)

Data Analysis (25 minutes):

This activity will help students see the major changes and continuities in age of consent laws. Divide the students into groups of two. Pass out copies of two secondary sources to each group: Source 10, the Age of Consent Laws Table, and the Age of Menarche in Norway chart. Explain to the class that menarche is a female's first menstrual cycle, and is often considered the beginning of puberty. Before beginning the analysis, ask the students the following two questions, either in a short discussion or in pairs:

- Are these primary or secondary sources? How do you know?

- Who was the author of each? What do you think his or her purpose was in creating this source?

- Describe the trends you see in the legal age of consent. What are their changes over time? Are there continuities?

- Describe the trends. Do you see in the age at which puberty begins? Are their changes over time? Continuities?

- What political, economic, and social forces might have led to the changes and/or continuities in the age of consent?

- Why might the changes and continuities in the age of consent vary from one region to another?

- What might have caused the age of puberty to change over time? (Note to teacher: many scholars believe that this is only due to improvements in nutrition during childhood, possibly during the prenatal period, too.)

- What might be the political, economic, and social effects of changes you see in both sets of data?

- Analyze the changes and continuities in age of consent laws in Western Europe between 1850 and the present. Be sure to include causes of changes and/or continuities in your thesis.

Next, ask the students to analyze the two sources by answer the following questions. Tell them to link their answers to specific evidence from the documents and readings they have encountered over the past two days.

Writing Assignment

Finally, have the students write a thesis statement (1-2 sentences) to address the prompt:

Socratic Circle (20 minutes)

This activity helps students understand the political and social implications of age of consent laws. Using a Socratic Circle, have students discuss how a state-defined concept of childhood could affect minority groups and/or colonized peoples. Ask the students to re-read Source 5 (Increased Age of Consent Speech), then discuss the following questions:

- Why were British officials anxious about changing the age of consent laws? What could the potential consequences of these changes have been?

- How might an 11-year old Hindu girl have reacted to the change in the law? How might her mother have reacted? Why?

- How might Muslims and/or Christians living in India have responded to the changes in laws? What implications might their reactions (vs. Hindu reactions) have for the British colonial government?

- How might changes in these laws affect the relationship between a state and minority groups living in that state (not a colony)? Use specific examples, such as Indian immigrants in England, Jews in Germany, or Africans in the United States.

Differentiation

Advanced Students

Have students evaluate the use of age of consent laws by historians (i.e. historiography) as a tool to trace the development of the concept of childhood and other stages of the lifespan (e.g., teenage years). Students should write a paper or create a presentation that responds to the following questions:

- Should historians use age of consent laws to trace the changes and continuities in the concept of childhood and/or teenage years? Why or why not?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of this approach?

- What other types of information should they also examine?

- What viewpoints are omitted by focusing on the legal age of consent? How could historians better understand those viewpoints? What types of documents would help in this effort?

Less Advanced Students

Help students understand what they are reading by creating a vocabulary list, and/or using shorter excerpts of the articles and documents rather than entire excerpts. Create scaffolding worksheets to help students record the changes and continuities they find in the documents; e.g., providing a grid for students to record the political, economic, social, cultural changes in each document.

Document Based Question

(Suggested writing time: 50 minutes)

The following question is based on the documents included in this module. This question is designed to test your ability to work with and understand historical documents.

Drawing on specific examples from the sources in the module, write a well- organized essay of at least five paragraphs in which you respond to the following prompt:

- Analyze the causes of the changes and continuities in age of consent laws in Western Europe between 1850 and the present.

- has a relevant, clear thesis that answers the question,

- uses at least six of the documents,

- analyzes the documents by grouping them in as many appropriate ways as possible. Does not simply summarize the documents individually, and

- takes into account both the sources of the documents and the creators' points of view. You may refer to relevant historical information not mentioned in the documents.

What additional sources, types of documents, or information would you need to have a more complete view of this topic?

Write an essay that:

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Stephen Robertson is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Sydney in Australia. He did his undergraduate studies in History and English at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, and his Ph.D. at Rutgers University, New Brunswick. Prior to coming to Sydney in 2000, he was a post-doctoral fellow at the American Bar Foundation in Chicago (1997-98), and the JNG Finley Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department of History at George Mason University (1998-99). He also taught for a semester at Massey University in New Zealand. His first book, Crimes against Children: Sexual Violence and Legal Culture in New York City, 1880-1960, explored the prosecution of sex crimes during the period in which new ideas about childhood transformed American laws regarding sexual violence. His current research explores everyday life in Harlem in the 1920s. He teaches courses on childhood and youth in modern America, the history of New York City, and digital history. In 2006, he was awarded a Carrick Australian Award for University Teaching Citation for Outstanding Contributions to Student Learning.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Sharon Cohen teaches AP World History and IB Theory of Knowledge at Springbrook High School in Maryland. She regularly presents papers on world history pedagogy at the annual conferences of the World History Association, the American Historical Association, the National Council for Teaching History, and the National Council for the Social Studies, served on the College Board's AP World History Development Committee, contributed articles to the online journal World History Connected, and published curriculum units in world history for the College Board and the online model world history project World History For Us All.

This teaching module was originally developed for the Children and Youth in History project.