Long Teaching Module: Children in the Slave Trade

Overview

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, an estimated 12 million Africans crossed the Atlantic to the Americas in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Used on plantations throughout the United States, Latin America and the Caribbean, enslaved Africans were shipped largely from West Africa. With an average life span of five to seven years, demand for slaves from Africa increasingly grew in the 18th century leading traders to take their supply from deep within the interior of the continent. Until recently, slave studies rarely discussed children's experiences in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. It has been estimated that one quarter of the slaves who crossed the Atlantic were children. Yet, a lack of sources and a perceived lack of importance kept their experiences in the shadows and left their voices unheard. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, potential adaptations, and essay prompts relating to the thirteen primary sources.

Essay

Introduction

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, an estimated 12 million Africans crossed the Atlantic to the Americas in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Used on plantations throughout the United States, Latin America and the Caribbean, enslaved Africans were shipped largely from West Africa. With an average life span of five to seven years, demand for slaves from Africa increasingly grew in the 18th century leading traders to take their supply from deep within the interior of the continent. Until recently, slave studies rarely discussed children's experiences in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. It has been estimated that one quarter of the slaves who crossed the Atlantic were children. Yet, a lack of sources and a perceived lack of importance kept their experiences in the shadows and left their voices unheard.

Enslavement

Like adults, children were unwilling participants within the slave trade that had a variety of sources. Children commonly found themselves enslaved as prisoners of warfare. When men were killed in battle, women, children, and the elderly became especially vulnerable. Those who were not killed or ransomed were sold into slavery. Commercial caravans frequently followed military expeditions, and waited patiently to exchange textiles and goods for captives. In some areas of West Africa, kidnapping was a popular method of acquiring children. Children were snatched while working in the fields, walking on the outskirts of town, or innocently playing outside away from their parents' view. So that communities could make ends meet during times of famine, families sometimes sold their children into slavery. Many children also found themselves as pawns or bargaining chips, sold into slavery to repay debts or crimes committed by their parents or relatives. Some parents sold children who were in poor health, required special needs, or perceived as evil spirits.

Journey to and Sale on the Coast

What happened in the days, weeks, or even months that followed their capture or sale was a whirlwind of events that had devastating effects on the psyches of the enslaved. Some children were sold immediately, and added to coffers of slaves bound for the coast. Others were sold several times over. Many children never left the interior and remained slaves in Africa. Others died somewhere on the route to the sea, along with thousands of other slaves, young and old.

For those children who made it to the coast, they were taken to a factory, castle, or trading post where they were sold to merchants who placed them in holding cells with other slaves. The merchants then stripped the children of any remaining clothing, and oiled their bodies with palm oil. Often coastal merchants shaved the heads. Once purchased, coastal merchants commonly branded the slaves with a symbol of the trading company or voyage owner on either their chest or back as a means of marking their commercial property and distinguishing their cargoes from the rest.

The Middle Passage

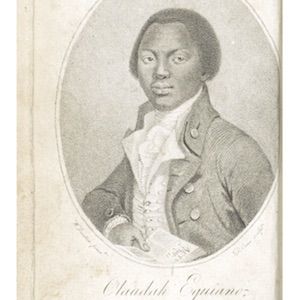

Traders generally defined children as anyone below 4'4" in height, and those deemed as "children" were allowed to run unfettered on deck with the women. Those traveling on deck occasionally received special treatment and attention from the captain and crew, who gave them their old clothes, taught them games, or even how to sail. Other children, like Ottobah Cugoano, refused to play or even eat. Some children, held tightly in the comforting arms of the women, cried throughout the night. Taller children, like Olaudah Equiano, were placed in the hold with adults where they experienced horrible, unsanitary conditions. Whatever their size, crying or failing to eat or sleep resulted in harsh punishment.

Although children received some preferential treatment, most children suffered experiences similar if not equal to the adults traveling alongside them. This preferential treatment and travel outside of the hold gave children a better chance of survival, but it did not shield them from corporal punishment, malnourishment, and illness. During the Middle Passage across the Atlantic that lasted anywhere from one month to three, children experienced high mortality rates. Many succumbed to the illnesses that accompanied every slaving voyage across the Atlantic, especially yaws and intestinal worms. Sometimes ill children were thrown overboard in the hope that their disease would not spread to the rest of the slave cargo.

A Demand for Children

Until the 18th century most trading companies had little or no desire to purchase children from the coast of Africa, and encouraged their captains not to buy them. Children were a bad risk, and many planters and traders who purchased them lost money on their investment. Because children (especially the young and infants) were vulnerable to disease, the cost of transporting them lowered overall profits margins. Furthermore, African children would not be able to perform hard labor or produce any offspring until they came of age. As a result, unless a planter or merchant requested a special order, children were extremely hard to sell in West Indian markets.

By the middle of the 18th century, however, planters economically dependent on the slave trade came to depend on children and youth. As the abolitionist movement increasingly threatened their slave supply, planters adopted the strategy of importing younger slaves who would live longer. As a result, youth became an attractive asset on the auction blocks of the slave markets. Ironically, abolitionist sentiment changed 18th-century definitions of risk, investment, and profit. As the plantocracy purchased more breeding women and children in order to save their economic interests, traders modified their ideas of profit and risk and ideas of child worth changed throughout the Atlantic World.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

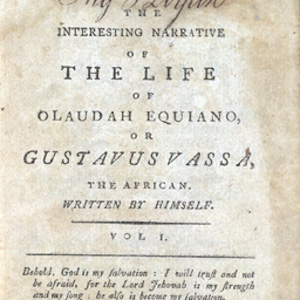

The primary sources are designed to provide a well-rounded examination of children's experiences in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The sources written by Olaudah Equiano, Venture Smith, and Ottobah Cugoano are excerpts of their published accounts of their personal experiences in the slave trade as children. Each of these sources offers a different perspective that will be of great value to students. While Venture Smith and Olaudah Equiano were rescued some time after their kidnappings, Ottobah Cugoano worked in the fields of a West Indian Plantation before obtaining his freedom in England. Equiano's narrative is particularly important, because (despite his young age) Equiano made the Middle Passage in the hold of the ship rather than in private quarters with the rest of the children.

By juxtaposing these narratives against images of the slave trade, students can begin to understand the brutalities of enslavement. In the first image, students see children chained in the same manner as adults in a slave coffle, which they can relate to Equiano's narrative. A second image depicts an advertisement for a slave ship that had recently docked in Charleston harbor listing an equal number of children and adults for sale, while a third shows a great number of children in the cargo of the liberated slave ship, Dhow. These two images, combined with quantitative evidence on the estimated number of children who traveled from Africa to the Americas from the 16th to the 19th centuries enable students to see shifts in supply and demand as more children entered the trade beginning in the 18th century. Students can then read the Dolben's Act of 1788, an English law that helped contribute to an increased number of girls and children in the trade.

Lastly, students can see the growing demand for children in an excerpted request made by Playden Onely to the members of the Royal African Company in 1721 for 130 children to be taken from West Africa to the West Indies for sale as slaves further supports the quantitative evidence supplied. After the success of this voyage, Onely contracted the RAC to deliver 500 children annually to specifically designated ports. While we have no evidence to support whether these voyages actually took place or for how long, Onely's contract request shows a growing demand for children before abolitionist sentiment came to a head in the late 18th, early 19th centuries, contrary to the accepted belief that children were a risk on Atlantic plantations.

Discussion Questions

- After reading excerpts from Equiano, Smith, and Cugoano, do you think that children received special treatment during the Middle Passage based on their age or size? Why or why not? Does the image of the slave coffle change or support your opinion?

- Prior to the threat that abolitionists posed to the future of the slave trade in the middle of the 18th century, children were seen as risky investments by slave traders and plantation owners. Why do you think that this was the case? What risks would children have posed?

- After abolitionism began to threaten the slave trade, and plantation owners began to fear its demise, children were no longer seen as risky investments. Why the change in planter and trader opinion? What benefit could a child bring to a trader or plantation owner? Why would children suddenly make a good investment?

Lesson Plan

by Susan Douglass

Time Estimated: two to three 45-50-minute classes

Objectives

- Examine children's experiences in the trans-Atlantic slave trade in terms of their capture, transport, and usage as laborers.

- Weigh evidence of the growing number of children taken in the slave trade and the causes and effects of their involvement.

- Assess factors in the continuation of the slave trade in the Americas, and in its fluctuation over time.

- Assess efforts by abolitionists to draw attention to the evils of slavery through publication of narratives and images involving children and the brutalities to which they were exposed.

Materials

- Printouts of primary sources sufficient for each student to have a full set of the texts and images in the Children in the Slave Trade Teaching Module. 1

- Six shallow boxes, bins, or baskets in which to collect citations written on half-sheets of paper.

- Enough half-sheets of paper to allow each student to write 10 responses.

- Three markers

Preparation

If possible, assign students to read as homework the primary sources in the Children in the Slave Trade Teaching Module. This activity will prepare students for writing an essay on the Document Based Question in this teaching module.

Day One

Hook

Display the image Advertisement for Sale of Newly Arrived Africans, Charleston, July 24, 1769 [Advertisement]. Ask students to view, read, and reflect on this advertising poster by thinking for 2—3 minutes and jotting down some historical questions it raises, and what element in the source raises those questions. What does it tell us, and what does it make us curious to know, focusing especially on the element of child slavery?

Responses might include: it tells us that children were being imported to the Americas for sale in significant quantities, that they were intended for use as laborers, and this trade began before a significant abolition movement was established. It raises historical questions such as: How many children were involved in the trade, and how did this change over time? How old were the children involved? How did slave owners and traders justify the increased risks and longer-term return on their "investment"?There are many other possibilities.

Activity

Divide students into three groups. Each group is assigned two containers, and goes to a corner of the room where chairs are set up. Divide the groups in half to represent opposing sides of each issue listed in the bullets below in #4.

Using the three bullet items of the DBQ, assign each group one issue to discuss using the documents. They will label the boxes per instructions that follow:

- The first group will read the slave narratives (The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano: Kidnapping, Slave Ship, Middle Passage, Slave Auction; A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture A Native of Africa, but Resident Above Sixty Years in the United States of America Related by Himself ; Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery: Slave Coffle, Middle Passage ) in order to identify and cite quotations of (a) evidence of the psychological and social damage done by the experiences related, and (b) evidence of the capacity for survival and resilience related by the narrators. Label the boxes "Damage" and "Resilience." Each half of the group will write citations from the documents on half-sheets of paper and place them in the corresponding box. These citations may include word lists, or they may be citations of whole phrases or sentences such as would be used to bolster an argument in an essay.

- The second group will read the other documents (any of the sources except the slave narratives) seeking evidence of the advantages and disadvantages for slave traders and slave owners. Label the 2 boxes "Advantages" and "Disadvantages." Each half of the group will write citations in support of either side and place the half-sheets in the corresponding box.

- The third group will look at any of the documents they believe are relevant to the issue of abolition. They will label their 2 boxes "Effective" and "Ineffective." Each half of the group will find citations of evidence that the publication of these documents would be effective in supporting abolition efforts, or might be either ineffective or serve as arguments for the continuation of slavery.

Working within the sub-groups, members will go over their findings on each side of the issue for 5–10 minutes. Then the three groups convene and discuss their findings as a whole on each issue. They will use the chart to prepare a summary of the group's findings, perhaps making a 2-column chart. This should take an additional 5—10 minutes.

Then the class comes together to present and discuss each group's findings on their issue. Part of the discussion could be to see if any of the documents a group DID NOT read are relevant to one of the three issues.

Day Two

The class will address the overarching document based question regarding the role of children in slavery during this period, putting all of the evidence together. The discussion is focused on analyzing the evidence as it illuminates the larger question. This discussion should include what the documents DO NOT reveal, and what type of information or documents might shed additional light on the question.

The students then receive the assignment to draft a DBQ essay using the documents, which would address all of the issues as they relate to the larger question. This will be assigned for homework.

Day Three (Optional)

The third class period could be devoted to reading student essays and critiquing their strategies, use of evidence, etc., first in small groups, and then as a class. Students use these critiques to revise their essays for completion of the assignment.

Differentiation

Advanced Students

- Assign the third discussion group in #4, above, since their task involves all of the primary sources, and requires a more subtle analysis of them.

- Have students students search for additional documents and images from The Atlantic Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Americas: A Visual Record, compiled by Jerome S. Handler and Michael L. Tuite Jr. Have them locate other images in the collection that may be relevant to the issue of children in the slave trade, and evaluate these sources in terms of their creators' point of view and their use as evidence.

Less Advanced Students

These students can be given more time and team support, or they can be asked to master just one of the three major issues raised in the document based question and use it to write an essay.

Texts include:

1

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano: Kidnapping; Slave Ship; Middle Passage; and Slave Auction;

The Dolben's Act of 1788;

Request: Playden Onely to the Royal African Company, 1721;

Advertisement for Sale of Newly Arrived Africans, Charleston, July 24, 1769;

Captured Africans Liberated from a Slaving Vessel, East Africa, 1884;

Slave Coffle, Central Africa, 1861;

A Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Venture A Native of Africa, but Resident Above Sixty Years in the United States of America Related by Himself; and

Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery: Slave Coffle, Middle Passage; and Children in the Slave Trade.

Document Based Question

by Susan Douglass

(Suggested writing time: 50 minutes)

Using the images and texts in the documents provided, write a well-organized essay of at least five paragraphs in response to the following question.

Evaluate the role of children in the Atlantic slave trade during the 18th and 19th centuries, based on analysis of evidence in the documents.

- How did the capture, transport, and sale of children affect these enslaved individuals

- What were the advantages and disadvantages of enslaving children to slave merchants and slave owners

- What do these documents indicate in terms of the possible effects of images and narratives of enslaved children on public opinion about slavery and on the abolitionist movement

Your essay should:

- have a clear thesis,

- use at least six of the documents to support your thesis,

- show analysis by grouping the documents into at least two groups,

- analyze the point of view of the documents, and

- recognize the limitation of the documents before you by suggesting an additional type of document or source to make your discussion more complete or valid.

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Colleen Vasconcellos is an Associate Professor of History at the University of West Georgia in Carrollton, Georgia. Her research focuses on childhood in the Atlantic World, in particular colonial Jamaica. In addition to being an editor and advisory board member of several H-Net listservs, Dr. Vasconcellos is author of Slavery, Childhood, and Abolition in Jamaica, 1788-1838 (2015) and co-editor of Girls in the World: A Global Anthology with Jennifer Hillman Helgren (2012).

About the Lesson Plan Author

Susan Douglass is a doctoral student in history at George Mason University, and also serves as education outreach consultant for the Al-Waleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University. Publications include World Eras: Rise and Spread of Islam, 622-1500 (Thompson/Gale, 2002), the study Teaching About Religion in National and State Social Studies Standards (Freedom Forum First Amendment Center and Council on Islamic Education, 2000), and teaching resources, both online and in print, including and the curriculum project World History for Us All, The Indian Ocean in World History, and websites for documentary films such as Cities of Light: the Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain and Muhammad:Legacy of a Prophet.

This teaching module was originally developed for the Children and Youth in History project.