Long Teaching Module: Children during the Black Death

Overview

The Black Death was the first and most lethal outbreak of a disease that entered Italy during the end of 1347 and the beginning of 1348 and then spread across Europe in the following few years. It is generally accepted (despite recent arguments to the contrary) that this most famous medieval epidemic was caused by bubonic plague. This disease, which was identified in the late 19th century, is endemic among some rodent populations around the globe today, but does not pose a major health risk due to the efficacy of modern antibiotics. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source. This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, potential adaptations, and essay prompts relating to the ten primary sources.

Essay

Introduction

The Black Death was the first and most lethal outbreak of a disease that entered Italy during the end of 1347 and the beginning of 1348 and then spread across Europe in the following few years. It is generally accepted (despite recent arguments to the contrary) that this most famous medieval epidemic was caused by bubonic plague. This disease, which was identified in the late 19th century, is endemic among some rodent populations around the globe today, but does not pose a major health risk due to the efficacy of modern antibiotics. The situation, of course, was very different in the Middle Ages. The Black Death was brought on, it is believed, by an epizootic, or animal epidemic, among marmots in central Asia that caused the flea (Xenopsylla cheopsis) which passes the bacillus (Yersinia pestis) to leave its preferred host and search for new sources of food, that is, human blood. Rats brought infected fleas, the plague vector, into Europe on ships leaving the Black Sea and shores of the eastern Mediterranean. The plague entered European sea ports and traveled inland along trade routes. The effect was devastating. Historians estimate death tolls of between a third and a half of the European population. For medieval Italy it appears that some urban areas, such as Venice, Florence, and Siena, suffered staggeringly high mortality rates of over 50 percent. How did people react to this awful catastrophe? The governmental records of Italian cities present a mixed picture of the actions of civic leaders in the face of plague. In some areas, cities rapidly passed laws that attempted to prevent the entrance and spread of disease. They renewed sanitation laws designed to reduce the presence of miasma, or bad air, which medieval people believed caused disease. Thus, laws curtailed the activities of butchers, tanners, or others who worked with animal carcasses that could rot and produce miasma. The mobility of people and goods, such as woolen cloths that may trap the miasma, was restricted. Other laws regulated the location of burials and disposal of corpses. In other cities, however, it appears that government was reduced to an ineffective shadow as officials died in huge numbers and efforts to replace them could not keep up. Church records have revealed the actions of ecclesiastical organizations. Bishops all over Europe consecrated new ground for burials and arranged intercessory processions. Priests were called to celebrate masses, give sermons, and lead their parishioners in processions of prayer to beg for merciful relief from the wrath of God, which was generally believed to have brought on the epidemic. Clerics urged all individuals to confess, be penitent, and carry out acts of pious charity in order to pacify God. Thus, evidence can be found that the various communities in medieval Europe made strong attempts to counteract and deal with the crisis. The popular view today of the Black Death, however, is one of social breakdown. This is because many chroniclers and literary authors of the time described the actions of townspeople in terms of panic, fear, and flight. Faced with a hideous—bubonic plague produces large, dark, and smelly swellings on its victims—and frightening new disease people fled to protect themselves. Chroniclers reported that doctors, clergy, and civil servants such as notaries refused to come to the aid of the ill. The chroniclers' accounts provide the most vivid picture of the social experience of this massive mortality and have become the standard description presented in World and Western Civilization textbooks. These accounts are at their most evocative and poignant when they discuss a principal theme of the topos of social chaos, namely, the abandonment of family members, especially children. The family was the heart of medieval European society. For medieval authors, the abandonment of children by their parents meant the specter of a society that had come unraveled at its core. It is important, therefore, to try to determine what really happened to children during the Black Death. We must remember that many medieval chroniclers were religious men who wrote with a moralizing message. It is possible that many wrote their accounts of events that happened in the world around them not with the modern notion of objectively reporting the facts, but instead to advise their readers to change their ways and lead more pious lives. This module presents a few typical examples of what medieval Italian chroniclers had to say about the experience of children and their families during the Black Death. We do not know what parents or children themselves said about their own experience because there remain few letters and no diaries from this time. Despite the paucity of descriptive sources, parents who were dying of plague often wrote wills in which they provided for the future of their families as well as their own souls. Students can compare the information —individually and in the aggregate—included in the chroniclers' literature with that contained in parents' wills. The archives of the town of Bologna contain the largest known number of testaments written during the Black Death. The mortality rate in Bologna may not have been as high as in Florence and Venice, but it suffered at least a 40% drop in population. The presence and contents of testaments during the epidemic can give us some indication as to whether parents were considering the fate of their children when they lay dying during the Black Death. These are formulaic documents that reveal little about the psychology of the testators themselves; they never even mention the fact that a massive epidemic was raging! Artistic sources are generally better at portraying powerful emotions, but there are no such sources that remain from the years of the Black Death. Instead, portrayals of themes related to death and morbidity became prevalent within a century of the Black Death as Europeans had become accustomed to the repeated outbreaks of plague. In fact, the Black Death was the first of a long series of plague epidemics that the people of early modern Europe suffered until the mid 1700s. It was by far the worst episode and therefore worth investigating how the most vulnerable part of the population--children--were treated during a time of social upheaval.

Primary Sources

Lesson Plan

Time Estimated: two to three 45-minute classes

Objectives

- Evaluate the reliability of various types of primary sources in regard to the effects of the Black Death on children and their families.

- Analyze and compare different types of available evidence on the physical and social affects of the Black Death.

- Develop possible explanations for the differences between contemporary (or near contemporary) narrative accounts of the Black Death and other types of evidence.

- Develop research questions that could lead beyond the current sources to suggest strategies for resolving the historical disputes raised by conflicting evidence.Gather the evidence presented in the documents and create a summary of the experience of the Black Death in visual or narrative form.

Materials

- Paper, regular notebook or white paper for individual or paired work, butcher paper or poster board for group work.

- Computer with Internet connection for viewing primary sources and accessing "Wordle."

- Web links and settings to enable Wordle and/or TagCrowd; and a word processor for pasting the primary sources.

- Documents from Teaching Module prepared as handouts.

Day One

Hook After introducing the topic of the Back Death, ask students to describe in a few keywords what they know about this occurrence in world history. Note the responses on the board. Then ask students how historians learned about the plague from available evidence. Make a list of possible sources of evidence the students identify. One type of evidence that might be surprising to students is a map that documents how widespread bubonic plague is today. (See 1998 plague reporting map from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.) Explain that the class will examine several different types of historical evidence about the plague. Activity Divide the students into three groups, according to the three types of primary source textual accounts (the Decameron and the Personal Accounts from Italy; the Health Ordinance; and the Testaments). Close Reading Activity First, have each group (or individual students) read the sources. Then, use the free applets (Wordle or TagCrowd) to make Word Clouds from the following texts, simply by choosing "Create," pasting the formatted or unformatted text into a window and pushing "Go:"

- Decameron excerpt and the Italian Accounts of the Black Death; pasting separately from the English, but combining the original Latin and Italian texts

- The Health Ordinance of Pistoia

- Combined text of the four testaments, and the graph of wills from Bologna.

The purpose of this exercise is to help students to see the pattern of language use in the sources. The word cloud will help students identify keywords in the original languages when they appear with equal emphasis in English (e.g., padre, abbandonava). The aim is to see what ideas and tone writers conveyed to their audience, as well as to gain a sense of the memory of the event in the writers’ minds. Students should not substitute the word cloud for a close reading of the text, but use it as an aid. Working on the three groups of sources, use the following questions as a guide for close reading:

- What do the word clouds for the English and original Latin and Italian communicate about the effect of the plague on the society of the time? Identify keywords in both languages. Identify descriptive nouns and adjectives. Identify terms for people? Are they general or personal terms? What does this say about the plague as an event across society? [Ans. people are described entirely in terms of their relation to one another, not in terms of class, vocation, or name.] Then read the annotation to the source. How do Boccaccio and the chroniclers portray the effect of the plague on social relations? Imagine the scene they describe, multiplied across whole cities. Does Boccaccio indicate different reactions among different social classes? How does the Decameron excerpt contrast with the frame of the stories, that is, a group taking refuge outside the city? Noting that these are not eyewitness accounts, what role might memory play in the substance and tone of the accounts, and what role does literary or moral purpose play?

- What does the word cloud indicate about official views of the plague's causes at the time? What words and their frequency in the ordinance indicate beliefs about the spread of the disease? What words are missing which might reflect medical knowledge today? [Ans: germs, fleas, blood] Then read the annotation to the source. Despite their lack of knowledge of germ theory and insect vectors, how did the measures targeted in the ordinance reflect practical observations about the spread of the disease? Is the frequency of attention to clothing, fabrics, and the absence of cleanliness entirely misplaced? Do you think that such an ordinance helped in any way? Was it enforceable?

- What does the word cloud indicate about the tone of the texts and the events they record? Make a list of the most frequent nouns, verbs, and other words describing people (names, vocations, relationships). Does the text include descriptive adjectives? To what do they refer? Read the annotations to the sources. Imagine the scene and the setting in which these wills were drawn up [students may wish to create a tableau of the scene using drawn figures or themselves acting out the parts.] Was it a scene of panic? What persons were present, and what were their relationships to the patient? Who was absent from the scene, and why? What concerns did each person present have and how did they bring their concerns to bear in making the testament? [Ans: patients taking care of family wealth, care of children who survived, priests getting donations for the church, debtors being paid, family members receiving shares] How would the ravaging plague have altered the normal process of drawing up a will? Using the graph of wills made during the plague months, and taking into account the officials who had to be present at will-making, discuss the difficulties the Church and the city faced during the epidemic. How likely is it that many people died without wills, or without registered wills? What is unusual about leaving the family wealth to a small child, whether son or daughter?

- NOTE: If at all possible, students should be encouraged to create word clouds individually or as a group, since the applet allows use of creative effects such as fonts, colors, and different word orientations that will inspire them to "see" the text in tone and substance.

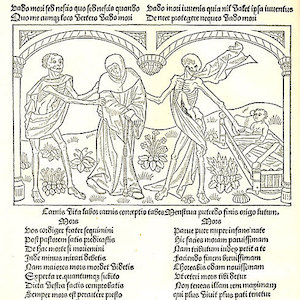

Following the individual or group work with the three different types of primary sources, ask students to give their impression of the effect of the Black Death on the social order, based on their set of documentary sources. Student responses should fairly clearly differentiate among the sources as to the effects, but also indicate common elements. The starkest contrast will be the scenes of impersonal, general breakdown of the social order in Boccaccio and the chronicles, compared with the orderly scenes of making wills in the homes of the sick, with an array of people present, personalized references, their attempt to keep families and relationships intact. How can historians today account for the difference? What role might memory, and what role might literary style play? The ordinance portrays an official response based on incomplete knowledge, but shows that practical observation had some value in defining preventative measures. What questions does the contrast in the sources raise? [EXAMPLES: Were priests willing to enter homes of the sick? How did they avoid the disease, or did they? How could there have been enough officials to witness and record wills during and after the epidemic? Could that account for the decline in numbers of wills after July?] Project the "Dance of the Dead" images or print them onto a 1-page handout. Read the annotations. Noting that these images are not directly related to the actual event of the Black Death, but existed as an art form before and after it, reflect on the following themes related to these popular images from the period. What messages do the images portray? What words can you recognize in the text accompanying the mural? Assuming generally high infant mortality even without epidemics, do you think people were emotionally attached to their children, knowing they might be carried away suddenly? How might mortality have differed among social classes? What indications of social class do the images portray? As public expressions of memory, what do they reflect in terms of attitudes toward death, and what moral lessons do they seem to project? Assign the Document Based Question below as an in-class essay or homework assignment. Follow your usual procedure for drafts, critique, revision, and finalizing. Extension Activity Use the World History For Us All teaching unit "Coping with Catastrophe: The Black Death of the Fourteenth Century, 1330 - 1355 CE" to assess the causes and effects of the plague in other parts of Europe and elsewhere in the world, and to see what historical source issues are raised by the materials in the lessons.

Differentiation

Advanced Students Advanced students may be asked to search for additional documents and images on the Black Death, including fuller versions of the ones excerpted in the lesson. A few students might research the course of the disease to contribute knowledge about how long it took from exposure to the disease to death, and how frequent known outbreaks of plague were in the following centuries. Less Advanced Students Remedial students could be asked to focus merely on the documents in English, or on a limited selection of documents from each group. The document-based question can be modified to allow more time, to use fewer documents for their essay. They may also be asked to provide a culminating assessment in a form other than an essay, such as a visual, literary or narrative account that can be graded on how well it reflects use of evidence and comparison among the documents.

Document Based Question

by Susan Douglass (Suggested writing time: 50 minutes) Using the images and texts in the documents provided, write a well-organized essay of at least five paragraphs in response to the following question. Describe and analyze the effect of the Black Death in 14th century Italy for its effect on families and children who became ill or who were survivors of parents and siblings who died, based on analysis of evidence in the documents.

- Did the social order break down completely during the panic produced by the epidemic?

- Were there social institutions that stabilized Italian society, and were efforts effective in preserving the social order and protecting its members?

- What additional evidence would help in deciding these questions (additional documents, types of records, etc.)?

- Your essay should:

- have a clear thesis,

- use at least six of the documents to support your thesis,

- show analysis by grouping the documents into at least two groups,

- analyze the point of view of the documents, and

- recognize the limitation of the documents before you by suggesting an additional type of document or source to make your discussion more complete or valid.

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Shona Kelly Wray is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Her book, Communities and Crisis: Bologna during the Black Death, is forthcoming. Wray is also a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Susan Douglass is a doctoral student in history at George Mason University, and also serves as education outreach consultant for the Al-Waleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University. Publications include World Eras: Rise and Spread of Islam, 622-1500 (Thompson/Gale, 2002), the study Teaching About Religion in National and State Social Studies Standards (Freedom Forum First Amendment Center and Council on Islamic Education, 2000), and teaching resources, both online and in print, including and the curriculum project World History for Us All, The Indian Ocean in World History, and websites for documentary films such as Cities of Light: the Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain and Muhammad:Legacy of a Prophet. This teaching module was originally developed for the Children and Youth in History project.