Short Teaching Module: European Maps of the Early Modern World

Overview

I use images of three historical maps for topics on colonial exploration and for interpreting historical evidence in undergraduate courses on history and historical methodology. I have several aims in using the maps. One is to study moments as well as change over time in Europeans’ conceptions of the world. Another aim is to show how maps, in the words of Joni Seeger in “Analyzing Maps” on this website, “reflect the priorities…of the mapmaker and his or her cultural context.” A third aim is to increase students’ awareness of how and why geographical knowledge is constructed. Analysis of historical maps invites students to ask why names and locations on world maps seem unfamiliar, and, likewise, whether modern maps would appear unfamiliar to people in the past. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

This short teaching module includes historical context and guidance on introducing and discussing the three primary sources.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

Why I Taught the Sources

I use images of three historical maps for topics on colonial exploration and for interpreting historical evidence in undergraduate courses on history and historical methodology. I have several aims in using the maps. One is to study moments as well as change over time in Europeans’ conceptions of the world. Another aim is to show how maps, in the words of Joni Seeger in “Analyzing Maps” on this website, “reflect the priorities…of the mapmaker and his or her cultural context.” A third aim is to increase students’ awareness of how and why geographical knowledge is constructed. Analysis of historical maps invites students to ask why names and locations on world maps seem unfamiliar, and, likewise, whether modern maps would appear unfamiliar to people in the past.

Easily accessible online in multiple collections, these maps serve as an excellent realm in which to discuss the issue of historical and cultural perspective and how perspective can shape or even distort representation of geographical knowledge. Additionally, I use these images as a means to explore the ways in which maps, in the words of Gerald Danzer in “Analyzing Maps” on this website, “are a product of a particular place, of a particular culture, a particular purpose.” In this manner, maps become more like other historical sources we study, particularly texts, with whose issues of authorship, audience, and perspective students should already be familiar. Study of maps in this way helps students gain a greater expertise in working with visual sources as historians.

How I Introduce the Sources

My teaching about European maps of the world begins with a background survey of Europe in the fifteenth century, touching on different religious, political, and economic factors that sparked European interest in the world beyond Europe. I emphasize that Europeans sought expansion of knowledge not from a sense of imperial superiority, which would shape colonialism over the next three centuries, but inferiority: the failure of the Crusades to retake Jerusalem for Christian control; the unreliability of overland travel to and from Asia through the Ottoman Empire; the rivalry with Islamic and African powers in the Mediterranean. I also focus on the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean as spaces important for experimentation and development of nautical technology, particularly the astrolabe and the lateen sale. If there is time available, it is worthwhile to demonstrate or simulate how these devices worked and why they were crucial for oceanic exploration.

Students are then invited to work with one or two partners to compare the three maps. A handy platform for this activity is Juxtapose (reviewed by Jessica Dauterive on this website), particularly suited for visual representations of change over time. This technique requires that the map images be formatted and annotated in Juxtapose and then embedded into a course website prior to class, and that students be able to access the course website individually during class time on laptop computers. Annotations of maps should include the cartographer, place, date and name of publication, and may include explanation of additional features, depending on how much guidance teachers wish to provide students versus having students interpret those features’ meanings and significance (see below for a bibliography).

Reading the Sources

The central activity to “read” the sources is an extensive comparative analysis. A suggested technique for students is to create handwritten lists compiling similarities or continuities and differences, which sharpens students’ observational and note-taking skills. For each column of similarities and differences, students should be encouraged to speculate not only what differences signify, but also continuities: Why does Europe’s position in the three maps diminish? But why is “North” consistently at the maps’ tops?

These points of comparison may be delineated further by the kinds of map features or concepts they illustrate. For example, the maps show landscapes, cities, and places that may not exist anymore, or that exist in transformed form. The maps also serve as records of historical processes and actual or potential relationships between Europeans, and between Europeans and others. And the maps reveal continuities or changes in how mapmaking cultures of which cartographers were a part saw their place in the world at the time the map was made.

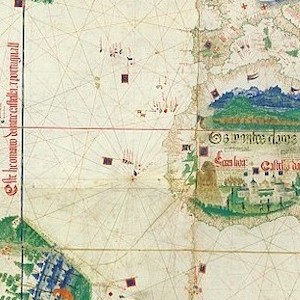

An obvious point about the three maps indicated is that the first two are nearly contemporaneous, appearing shortly before and after Columbus’s first transatlantic voyage. The first two maps’ origins on either side of Columbus’s famous 1492 voyage, helps illustrate that voyage’s impact on European cartography and imagination of the world. Students may be asked about the relationship between the Cantino map and the definitive event in modern history, the rise and extent of European colonialism.

In the first map, Martellus displays a keen interest to make use of new information from Portuguese explorations around southern Africa: In his voyage of 1487-88, Bartholomeu Dias had rounded the Cape of Good Hope. The Martellus map, in fact, suggests a hasty modification of its lower left, announcing the new fact, as stated in one of the map’s legends, that the Indian Ocean was not land-locked. Martellus’s map, with its center in Eurasia and numerous places newly identified along West Africa, reflects a Europe grasping to understand implications of revolutionary information that the Earth might not consist of a single land mass, which had been the assumption of medieval cartography.

The second map is the earliest map showing the recent discoveries by another Portuguese explorer, Vasco da Gama, who, using a new portable version of the classical astrolabe, charted Brazil, Newfoundland, Greenland, Africa, and India. Besides the new geographic knowledge Gama brought, he also initiated nautical trade in spices, jewels, precious metals, and hardwoods, whose sources the map portrays in uniformly vibrant green. But the Cantino map is of Italian origin, a provenance that suggests the fierce rivalry among Europeans for new geographic knowledge arriving regularly when ships of the Age of Discovery docked in what was at the time the world’s most important city.

Reflecting Italian traders’ recognition of the threat to their monopoly on luxury goods brought overland from Arabia, India, and East Asia, Cantino, an Italian agent, commissioned anonymous Portuguese sailors and cartographers to make a map showing all the latest geographic discoveries. Suggestive of the coming coincidence of political and religious interests in Europe to know of the world’s resources and peoples in order to master them, the map expresses imperial rivalry: the blue vertical line on the left marks the imperial division of newly discovered lands outside Europe between Portugal and Spain, according to the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. The Cantino map’s features and emphases on trade destinations across hemispheres would shape European cartography and expansion for the next century.

The third map of J. G. Bartholomew, appearing in the early twentieth century, dramatized the narrowness of European cartography three centuries earlier. It does so by superimposing the Americas on a reconstruction of a 1474 map of Italian cartographer Paolo Toscanelli. Relying on information of Marco Polo, Toscanelli estimated that Cathay, an historical European name for China, lay about half as far from Lisbon, Portugal – the prominence of each place on the map should be pointed out – as modern cartographers have measured. And Toscanelli placed Cippangu, or Japan, some 1,500 miles east of mainland Asia. Toscanelli’s map had been lost by the sixteenth century, but Columbus likely carried it with him in 1492; his reliance on it caused him, initially, fail to realize he had found a new continent.

Bartholomew’s map, appearing near the other end of the long era of European colonialism, signified, both literally and figuratively, the transition of global prominence from Europe to America. Its display of both pre-Columbian, or “false,” and post-Columbian, or “true” representations of the Atlantic Ocean, renders nearly comical early modern Europeans’ mapping of the world from the perspective of a commerce-oriented ambition to sail westwards to reach the Spice Islands and Asia. Bartholomew’s map also suggests the emergence of America in the world, in the middle yet not quite visible. Questions may be raised with students about what to make of the fact that while all three maps were made by Europeans, in only the first two is Europe in the middle.

Bibliography

Burnham, Michelle. “Oceanic Turns and American Literary History in Global Context.” In Turns of Event: Nineteenth-Century American Literary Studies in Motion, ed. Hester Blum. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 2016. 151-71.

Rickey, V. Frederick. “How Columbus Encountered America.” Mathematics Magazine 65 (1992). 219-225. Accessed April 10, 2021. doi:10.2307/2691445.

Siebold, Jim. Chart for the navigation of the islands lately discovered in the parts of India, known as the “Cantino World Map”. MyOldMaps.com. May 22, 2020, https://www.myoldmaps.com/renaissance-maps-1490-1800/306-cantino-world-map/306-cantino.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2021.

Siebold, Jim. Martellus’ World Maps. MyOldMaps.com. October 18, 2020, https://www.myoldmaps.com/late-medieval-maps-1300/256-henricus-martellus/256-martellus.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2021.

Credits

Tim Roberts is an historian of the United States and the Atlantic world through World War I. He teaches courses in American history, historical methodology, public history, and digital history at Western Illinois University. He has written books on the history of American exceptionalism and on the American Civil War, focused on the war's transnational and military aspects.