Short Teaching Module: Sick Men in Mid-Nineteenth-Century International Relations

Overview

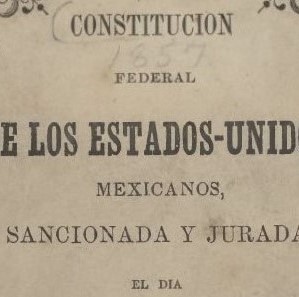

I use political cartoons, newspaper stories, and excerpts from government documents to show different perspectives of a country’s power and foreign relations. I have several aims in using the texts. One is to accustom students to reading and interpreting state documents to understand their legal impact and what they suggest about their political context, in this case, decrees by Ottoman Sultan Abdulmecid I of 1850 and 1856, and the Mexican republic’s Constitution of 1857. Attitudes held by many middle-class people as well as rival statesmen in Europe and the United States towards the Ottoman Empire and Mexico are, meanwhile, reflected in the respective cartoons and the newspaper source. Commentators in Europe and the United States used the metaphor of a “sick man” to characterize both Ottoman and Mexican authorities. The term was first used by Czar Nicholas I of Russia in 1853 to describe the Ottoman Empire. The concept of a “sick man” connoted the economic struggle, sociopolitical turmoil, and cultural backwardness of weak countries vulnerable to foreign exploitation, including annexation.

By comparing the government documents and popular sources, students are challenged to explore why those negative images circulated, how much truth there was to them, and what different kinds of sources reveal and obscure concerning a government’s domestic authority and international standing. Students should be able to articulate the tension gripping governments faced with demonstrating central state authority and stopping secessionist movements, and, meanwhile, granting equal rights and adopting liberal institutions like those of nearby imperial powers – Britain and France in the Ottoman case, the United States in the Mexican case.

For information on comparative history, see this primer by Kenneth Pomeranz.

The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below.

Click on the images or text for more information about the source. This short teaching module includes historical context and guidance on introducing and discussing the primary sources.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

Why I Taught the Sources

I use political cartoons, newspaper stories, and excerpts from government documents to show different perspectives of a country’s power and foreign relations. I have several aims in using the texts. One is to accustom students to reading and interpreting state documents to understand their legal impact and what they suggest about their political context, in this case, decrees by Ottoman Sultan Abdulmecid I of 1850 and 1856, and the Mexican republic’s constitution of 1857. Attitudes held by many middle-class people as well as rival statesmen in Europe and the United States towards the Ottoman Empire and Mexico are, meanwhile, reflected in the respective cartoons and the newspaper source. Commentators in Europe and the United States used the metaphor of a “sick man” to characterize both Ottoman and Mexican authorities. The term was first used by Czar Nicholas I of Russia in 1853 to describe the Ottoman Empire. The concept of a “sick man” connoted the economic struggle, sociopolitical turmoil, and cultural backwardness of weak countries vulnerable to foreign exploitation, including annexation.

Comparing the government documents and popular sources challenges students to explore why those negative images circulated, how much truth there was to them, and what different kinds of sources reveal and obscure concerning a government’s domestic authority and international standing.

How I Introduce the Sources

My teaching about this topic begins with a background survey of diplomatic relations and state-building in the first part of the nineteenth century. The topic highlights the intense competition in Europe and North America for territory and the tension arising over racial and religious conflicts within and across empires (within which I include the United States). Discussion also includes an overview of constitutional government, individual rights and citizenship, and federalism, though students could benefit from prior background in these political concepts. Teaching then shifts to some important historical events, including establishment of the Mexican republic, the Mexican-American War, nationalist uprisings in the Ottoman Empire and its organization according to religious communities, and the Crimean War (see bibliography).

Students should be able to identify some parallel patterns in the situations of Mexico and the Ottoman Empire, particularly pressure exerted by powerful neighbors regarding both their sovereign territory, which was vulnerable to foreign annexation, and an influence to reform their governments to grant civil liberty. Students should be able to articulate the tension these governments faced to balance demonstrating central state authority and stopping secessionist movements with the granting of equal rights, declaration of a single identity among all residents, and adoption of liberal institutions like those of nearby imperial powers – Britain and France in the Ottoman case, the United States in the Mexican case.

Reading the sources

After students digest background information, they may consider the primary sources. Consideration of the sources requires study of them both individually and by comparison to one another. Students may be most comfortable first approaching the cartoons. Given that in the cartoons, figures represent countries, what attributes of those countries are suggested or emphasized, and what political messages does each cartoon convey? What international situation does each cartoon reflect? Whose perspective is reflected in each cartoon, and whose perspective is left out? And how may the cartoons be compared – in what ways are the figures alike “sick men”? Are there “remedies” proposed?

Next, it is suggested that attention turn to the newspaper story, which makes an explicit comparison between the circumstances of the Ottoman Empire and Mexico. Students may read the story individually or in groups, then discuss what features of the two countries, again, are compared, and what the overall argument of the story is. Students should consider the fact that the story appeared in an American newspaper, and was based on a similar story in a British newspaper. What does that authorship suggest about perspective? Hopefully, students will grasp that the story suggests that the United States annex Mexico, as Russia was, at the time, attempting to annex parts of the Ottoman Empire. Discussion of this point might focus on several questions: what were the story’s arguments for why the United States should annex Mexico? Why didn’t the United States annex Mexico at the time? And what might have happened subsequently if the United States had annexed Mexico?

Next, students should consider the other textual sources, including the two Ottoman imperial decrees and the Mexican constitution. Students should be given adequate time to study details of these sources and take notes for asking questions to clarify the documents’ assertions. Students might be given guiding questions, such as direction to find examples of certain concepts or practices, especially civil rights or liberties, laws concerning religion, and examples of outside or international influence. Regarding the Ottoman edict of 1856, attention could focus on paragraphs 6, 9, 15, 17, 18, and 24. Regarding the Mexican constitution of 1857, attention could focus on articles 2, 7-10, 12, 20, 22, 26, 27, 30, 39, 40, 50, 117, and 128. Students should also take note of how the documents are different from one another – where did authority originate in the Ottoman Empire, and where in Mexico? And what was the role of established religion in the two countries’ national documents?

Finally, students should reflect on their study of the documents in this lesson as a whole. How do the cartoons compare to the textual sources? Considering the respective authors of the sources and the sources' different purposes, how do the sources authored, respectively, by Ottoman and Mexican authorities express national power, whereas the point of the newspaper story and the cartoons is to express national weakness? Can these differences be explained or reconciled? And what are the strengths and weaknesses of each kind of historical source in this lesson?

Bibliography

Cirakman, Asli. From the "Terror of the World" to the "sick Man of Europe": European Images of Ottoman Empire and Society from the Sixteenth Century to the Nineteenth. New York: Peter Lang. 2005.

Pletcher, David. Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. 1973.

Yang, Jui-sung. “From Discourse of Weakness to Discourse of Empowerment: The Topos of the ‘Sick Man of East Asia’ in Modern China.” In Discourses of Weakness in Modern China. Ed. Iwo Amelung. Frankfurt, Germany. Campus Verlag. 2020. 25-78, esp. 33-39.

Zumoto, Motosada and Masujiro Honda. “China, Turkey and Mexico.” Oriental Review 2 (1912). 197-199.

Credits

Tim Roberts

is an historian of the United States and the Atlantic world through World War I. He teaches courses in American history, historical methodology, public history, and digital history at Western Illinois University. He has written books on the history of American exceptionalism and on the American Civil War, focused on the war's transnational and military aspects.