Long Teaching Module: Education in the Middle East, 1200-2010

Overview

In recent years, westerners have been fascinated by the education of children in the Middle East, raising concern over whether or not schools teach extreme radicalism or anti-Americanism. The Arabic word madrasa, which literally means "school," has come to imply in the minds of some pundits and politicians a pro-terrorism center with political or religious affiliation. The situation was very different in the pre-modern era, when schools in the Middle East were world renowned: students from as far away as Spain traveled to regions such as Iraq to study with noted teachers. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, potential adaptations, and essay prompts relating to the twelve primary sources.

Essay

Introduction

In recent years, westerners have been fascinated by the education of children in the Middle East, raising concern over whether or not schools teach extreme radicalism or anti-Americanism. The Arabic word madrasa, which literally means "school," has come to imply in the minds of some pundits and politicians a pro-terrorism center with political or religious affiliation. The situation was very different in the pre-modern era, when schools in the Middle East were world renowned: students from as far away as Spain traveled to regions such as Iraq to study with noted teachers.

In the early days of the Islamic community in the Middle East (i.e., from the death of the prophet Muhammad in 632CE through the four Islamic caliphates and the Umayyad Dynasty in 750CE), the leading Muslims of the Arabian peninsula employed tutors or owned slaves to teach their sons the basics of religion, to read and write, to use the bow and arrow, to swim, and to be courageous, just, hospitable, and generous. The elite expected their daughters to attain skills relating to the household as well as the basics of religion, and sometimes to learn music, dance, and poetry.

The majority of children in rural areas learned how to work the land from their families. The only formal education they received would be from the kuttab, or mosque school, listening to Qur'an readers in mosques, or from informal exchange of information in the family.

In urban areas, boys typically began apprenticeships at around eight years of age to master a craft or skill. In terms of higher education, if a child had memorized the Qur'an (by about 12 years of age) he would often then travel around the Islamic world in quest of a teacher who had an understanding of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). Students would gather around these teachers in mosques and master the teacher's approach to law without much questioning.

With the consolidation and cultural development of the Islamic empire during the Abbasid Dynasty (750-1258CE), a systematic method of schooling was established in the Middle East for both elementary and higher education. This remained the main form of education until the 20th century.

A maktab, or "elementary school," was attached to a mosque and the curriculum centered on the Qur'an, which was used to teach reading, writing, and grammar through recitation and memorization. Physical education was emphasized in childhood education because Islam gives importance to the training of the body as well as the mind. (Children of wealthy and prominent families continued to receive individual instruction in their houses.)

After attending a maktab, a student could attend a madrasa, or "higher education institution," attached to a mosque. Individual donors, rulers, or high officials funded these through pious endowments. The endowment funds maintained the building, paid teacher salaries, and sometimes provided stipends for students.

The madrasa founder generally set the curriculum. With a focus on fiqh, schools sometimes also taught secular subjects, such as history, logic, ethics, medicine, and astronomy. Memorization was a critical aspect of a student's training in law. The material memorized formed the base used by jurors to practice ijtihad, or the process of making a legal decision by independent interpretation of legal sources.

The most famous madrasas in the Middle East were Cairo's Al-Azhar, founded in the 10th century, and Baghdad's Al-Nizamiyya, founded in the 11th century. (Medical schools were usually attached to hospitals.)

The period of the Abbasid Dynasty is often referred to as the Golden Age of Islam, due in large part to the thriving centers of learning. Scholars during this time translated, preserved, and elaborated Greek philosophy (later used in European universities). They also made advances in algebra, medicine, trigonometry, mechanics, optics, visual arts, geography, and literature.

During the early-modern era (1500-1800), education continued to flourish under the Ottoman and Safavid Empires. One study suggests that up to half of the male population was literate in Cairo at the end of the 18th century, implying that maktabs were numerous.

The madrasa continued to be constructed as part of the mosque complex, reflecting the importance of education to religion and the sense that education took place within the religious framework. Scholarship under the Ottomans and Safavids centered on the notion that the most advanced science came from Islam and that scholars before them knew best. This was in contrast to Europe during the 19th century, where higher education in new types of institutions of learning began to free itself from church control to embody the Enlightenment value of questioning religion (i.e. putting the laws of science over the laws of God), although reform of the older universities in Europe proceeded slowly.

In the face of Europe's growing power from advanced technology and commercial wealth, Ottoman rulers entered the modern era (1800-present) with a series of educational reforms. The reforms aimed to modernize the empire by adapting aspects of western life. (In contrast, Iran, under the Qajars, did not undergo the same level of educational reforms.)

The Ottomans sent envoys to Europe to translate their scholarship and learn new scientific discoveries. They secularized society such that educational opportunity became equal for all subjects in state schools. In cities such as Istanbul, Cairo, and Tunis, reforming governments established specialized schools to train officials, officers, doctors, and engineers. Some contesting voices in the Ottoman Empire argued, however, that the problems of the Empire were not from a lack of western ways, but from a need to return to the ways of the early age of Islam and the Golden Age.

Nonetheless, by the end of WWI, almost all of the Middle East had fallen under European colonial rule. The maktab and madrasa system of education began to wane in the place of French and British schools. These schools had limited enrollment due in large part to their scarcity in number; access was restricted to a select local elite trained to enhance colonial administration. Study in the maktab and madrasa no longer led to high office in government service or the judicial system.

Although the colonizing authorities introduced compulsory schooling measures of one kind or another, they often failed to include sufficient funding in colonial budgets, so the percentage of the total child population in schools remained dismally low. Children in rural areas who attended school often studied for a half day and worked the other half. In Algeria, for example, by 1939 the number of secondary school graduates was in the hundreds for the entire country.

Various types of private Islamic schools existed as alternatives to government secular schools, but the colonial governments sought to exercise close control through subsidies, curriculum expansion, and inspection systems. Religious schools often served—as they did in European efforts to extend education to the middle and lower classes—as a base from which to build capacity. A small number of European and missionary schools, as well as some indigenously operated Christian schools existed alongside the government and Islamic schools. In cities, these Christian schools of various denominations sometimes gained importance as institutions where children of elites accessed European education. In this way, a two-tiered education system developed under colonialism. In all of these systems, girls were able to acquire a nominal education; if it continued, it was usually in the form of training for teaching, nursing, or midwifery.

Post-colonial governments in the Middle East prioritized mass popular education to build strong nations. Egypt's Gamel Abdel Nasser, for example, promoted free education and promised each graduate a position in the public sector. In countries such as Egypt, Syria, Morocco, and Algeria, schools underwent a process of "arabization." This meant a focus on teaching Arabic language and culture. Traditional schools either closed or became incorporated into the state system. Iran, in contrast, had never been colonized. It became increasingly westernized in the mid-20th century, until the Revolution and subsequent Islamization of the state and schools.

While access to education has improved dramatically in the Middle East in the second half of the 20th century, the public education system tends to suffer from overcrowded classes led by poorly-trained, overworked teachers with inadequate materials. The curriculum is for the most part secular, and when the history of Islam is taught, the goal is not to incite children to violence. Many families must hire private tutors to help children with their end of the year exams, which emphasize the memorization of massive amounts of material. If children fail these exams, they can conceivably remain in the same grade level for as many years as it takes to pass, or they fail to qualify for secondary or post-secondary training of their choice. A very small percentage of families can afford to send their children to private European or American schools in the Middle East, which provide a western-style education.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

Strategies

This teaching module provides a wide variety of sources to explore the history of schooling in the Middle East, a topic that is largely misunderstood in the west. Schools in the Middle East today take various forms, from secular to Islamic. Current research of textbooks in the Middle East finds little in them that could be construed as incitement to violence in the name of religion, or for any other reason. Many western pundits, politicians, and academics portray schools in the Middle East as breeding grounds for terrorists and Islamic extremists. These schools are also portrayed as unchanging institutions, which implies that they have not evolved since medieval times and that even in medieval times the schools were static.

The truth is that medieval Islamic schools produced a wealth of knowledge that European scholars translated from Arabic after the 12th century, and incorporated into institutions of higher learning between the 14th and 16th centuries. Furthermore, in today's world, schools in the Middle East take various forms, from secular to Islamic. Current research of textbooks in the Middle East finds little in them that could be construed as incitement to violence in the name of religion, or for any other reason. Wherever military struggle is mentioned, it is always in the context of defense against an aggressor.

With the first four sources, encourage students to explore the various characteristics of schooling in the Middle East in medieval times. In regards to the emphasis on memorization, students should understand that there were scholars who challenged this accepted method, such as Ibn Khaldun. Likewise, students should themselves grapple with finding the strengths in a method of instruction that emphasizes memorization. Do students agree with the Ottoman reformers who thought that a modern nation must have an educational system similar to Europe's? Do students think that the various early 20th-century Middle Eastern reformers' justification for schooling girls marked a step towards modernization?

They key problem governments in the Middle East face today in regards to the educational system is not extremism, but rather identity crisis, underfunding, and conflict. The article on schools in Algeria since independence shows that colonization created an abused collective psyche that initially sought to heal itself through insulation. Might the educational system in Iraq be on a similar path? What evidence do we have that people in the Middle East value education, despite the challenges they have faced in its pursuit in the 20th century?

Discussion Questions

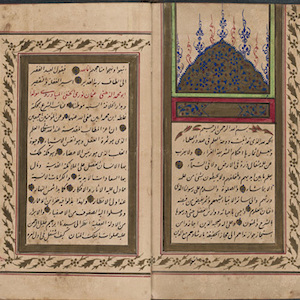

- Look at the two ijazahs (diplomas) from medieval times. Even without reading the Arabic, what stands out to you most about them? For a system of education that emphasized rote memorization, do you discern a sense of creativity?

Possible answer:

Creativity can perhaps be discerned in the designs on the diplomas and the difference in appearance between the two. The annotation also mentioned that the diplomas used individualized flattery.

- Imagine you are in a debate with Ibn Khadlun. Present an opposing argument, including in your stance some of the merits to memorization that el-Baghdadi lists in his autobiography as well as some of the achievements medieval Islamic society made for humankind as a whole.

- Envisage yourself a student in a medieval maktab: Who would be in your class with you? What would you learn? How would your progress be evaluated? To what might you aspire in terms of higher education?

- Arguably, schools can be viewed as a means of controlling a population. Provide examples of how this has been attempted through physical and intellectual means, particularly under colonialism and the independent nation-state.

Possible answer:

Some examples to include in the answer would be: schools were funded by endowments in the medieval period and the benefactors set the curriculum; as the devshirme illustration indicates, when first conscripted, the boys were dressed in red to avoid their escape; and, the reform of education during the tanzimat was for the sake of the nation and military; education under the colonists was intended to benefit the British; education in post-independence countries had economic and social development as a main goal. Students might also point out instances of where the student is a free agent, such as in medieval times when he would travel from scholar to scholar seeking knowledge. Generally speaking, students can discuss the role that the individual student can play in thinking on his/her own and not being fully controlled.

- After you summarize the New York Times article about education in Algeria, analyze its tone. What approach does the author take to the issue? Do you notice any bias? Does the author leave out any important issues? How do you think context influences content? What information might this article reveal about modern-day US concerns regarding education in the Middle East?

- The podcast on young people's accounts about war in Iraq focuses almost entirely on their experiences with school. What do you think are the advantages and disadvantages to studying political issues through educational institutions? In your answer, reflect as well on some of the other sources provided.

- Look at the two ijazahs (diplomas) from medieval times. Even without reading the Arabic, what stands out to you most about them? For a system of education that emphasized rote memorization, do you discern a sense of creativity?

Possible answer:

Creativity can perhaps be discerned in the designs on the diplomas and the difference in appearance between the two. The annotation also mentioned that the diplomas used individualized flattery. - Imagine you are in a debate with Ibn Khadlun. Present an opposing argument, including in your stance some of the merits to memorization that el-Baghdadi lists in his autobiography as well as some of the achievements medieval Islamic society made for humankind as a whole.

- Envisage yourself a student in a medieval maktab: Who would be in your class with you? What would you learn? How would your progress be evaluated? To what might you aspire in terms of higher education?

- Arguably, schools can be viewed as a means of controlling a population. Provide examples of how this has been attempted through physical and intellectual means, particularly under colonialism and the independent nation-state.

Possible answer:

Some examples to include in the answer would be: schools were funded by endowments in the medieval period and the benefactors set the curriculum; as the devshirme illustration indicates, when first conscripted, the boys were dressed in red to avoid their escape; and, the reform of education during the tanzimat was for the sake of the nation and military; education under the colonists was intended to benefit the British; education in post-independence countries had economic and social development as a main goal. Students might also point out instances of where the student is a free agent, such as in medieval times when he would travel from scholar to scholar seeking knowledge. Generally speaking, students can discuss the role that the individual student can play in thinking on his/her own and not being fully controlled. - After you summarize the New York Times article about education in Algeria, analyze its tone. What approach does the author take to the issue? Do you notice any bias? Does the author leave out any important issues? How do you think context influences content? What information might this article reveal about modern-day US concerns regarding education in the Middle East?

- The podcast on young people's accounts about war in Iraq focuses almost entirely on their experiences with school. What do you think are the advantages and disadvantages to studying political issues through educational institutions? In your answer, reflect as well on some of the other sources provided.

Lesson Plan

Lesson Plan: Education in the Middle East

by Heidi Morrison

Time Estimated: two to three 45-minute classes

Objectives

- Be able to accurately and succinctly summarize a document, in the context of the history of schooling in the Middle East.

- Articulate how context influences content, in regard to various documents published over time about schools in the Middle East and also in regards to one's own knowledge.

- Gather information about the history of schooling in the Middle East in order to state characteristics that can be used when grappling with regional stereotypes.

- Use the information about the history of education in the Middle East to formulate opinions on current-day debates about education's role in society.

Materials

Students must come to class already having read the primary documents (in the case of the podcast, listened to it and recorded notes). For this lesson, students will need a hard copy of the documents and/or their notes. A notebook, paper, and pen are also required.

Hook

Share with the students this quote from a widely-cited article in the New York Times Magazine reporting that in Pakistan, "There are one million students studying in the country's 10,000 or so madrasas, and militant Islam is at the core of most of these schools." 1 Tell students that other commentators have suspected that an equally militant spirit pervades schools in predominately Muslim countries.

Ask students what comes to mind when they think about schools in the Middle East, a predominately Muslim area of the world. Have them write down their thoughts anonymously and collect them to read out loud. They may mention variations of such terms as "jihad factories" or "backwards" or "outposts of medievalism." If these subjects come up, ask students to speculate about how and why schools in the Middle East have developed such negative associations with extremism.

Instruct

Explain to students that they will learn about the history of schools in the Middle East. They will study primary sources that will help them understand the characteristics of schools in the pre-modern Middle East as well as the contemporaneous debates around schools. They will also study primary sources that will help them understand the changes that these schools have undergone in entering the modern era. This lesson will help students formulate an informed image of schools in the Middle East, which is the ultimate goal of the Document Based Question.

First Activity

The first activity will focus on piecing together information from the various sources about how schools functioned in the pre-modern Middle East.

Divide the class into four groups. Tell them that each group will be assigned part of the larger project that is to create an imaginary 11-year old male pupil living in the Middle East in the 10th century. After each group completes their part of the project, they will present to the entire class. Every student in the class is responsible for learning all components of the material. Assign each group one of the following topics to describe in detail about the virtual student and tell them to base their answers on the first four sources provided in this module:

- Why he goes to school;

- What he learns in school;

- How he is taught in school;

- His aspirations for the future.

Second Activity

Students will be challenged to advance their understanding of the history of schools in the Middle East, as well as to improve their critical reading skills.

Divide the class into six groups and assign each group one source from sources 6–12 to summarize. Tell students to pay attention to what the sources say about changes schools in the Middle East have undergone in the modern era. When the students are ready, have them present their group summaries to the class.

Now tell the students that there is as much information in what sources from what they don't say as in what they say. Tell the students to return to their groups and decipher new information based on what is not included in their source. When the students are ready, have them present their ideas to the class.

A final step to this activity is to have the students return to their groups and talk together about how context influences content. Students should discuss how the information they garnered from the documents was influenced by what they know about the author of the source and/or what was happening in society at the time of its production. This discussion should force students to reevaluate the information they presented to the class thus far. Each group should do one final presentation to the class about what they know from their assigned document about education in the Middle East in the modern era.

Third Activity

Students will synthesize what they covered in the last two activities.

In a general class discussion, have the students recap what they find to be the main characteristics of education in the Middle East over the pre-modern and modern eras.

After this is completed, tell students there are many ways in which the history of education (as a field) contributes to current-day debates. Now that students possess a wide breadth of knowledge about the history of schools in the Middle East, ask them to articulate their opinions on the following topics:

- Do you think that schools are a means of controlling a given population?

- What do you think are the best pedagogical tools for learning?

- How does access to education, or lack thereof, impact society?

Many students may have a tendency to base their opinions about these questions on their experience/knowledge of schooling in the west. Ask the students to formulate opinions in the framework of their knowledge of the history of schooling in the Middle East. This exercise will force students to integrate what may have previously been foreign to them (schooling in the Middle East) into how they construct their worldview.

If there is time, conclude by telling students to "shift gears" and write down all the associations that come to mind when they hear the words "women in the Middle East" or "religion in the Middle East." Listen to their responses and ask why you might conclude a lesson on schooling in the Middle East with such a question. Encourage students to take away from this module not only information about schooling in the Middle East and an exposure to larger interdisciplinary debates on education, but also an awareness that just as the texts are shaped by their context, so too is our knowledge.

1 Goldberg, "Inside Jihad U.; The Education of a Holy Warrior," New York Times Magazine, June 25, 2000.

Document Based Question

(Suggested writing time: 50 minutes)

Using the images, texts, and audio recording in the documents provided, write a well-organized essay of at least five paragraphs in response to the following prompt:

- Imagine you are at a dinner party and the topic of conversation turns to international politics. One person at the table makes the statement, "Since ancient times, children in the Middle East have been taught violence against infidels." Using at least six primary sources related to the history of schooling in the Middle East, write an essay that responds to this theoretical statement.

- have a clear thesis,

- use at least six of the documents to support your thesis,

- show analysis by grouping the documents into at least two groups,

- analyze the point of view of the documents, and

- recognize the limitation of the documents before you by suggesting an additional type of document or source to make your discussion more complete or valid.

Your essay should:

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Heidi Morrison is an assistant professor of modern Middle East History at the University of Wisconsin- La Crosse. She is currently writing a book entitled State of Children: Egyptian Childhoods in an era of Nationalism, Modernity, and Emotion. Heidi is also the editor of the forthcoming The History of Global Childhood Reader (Routledge Press, 2011). She is working on a project on the history of boys and mental health in Palestine.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following institutions for primary sources:

- ABC National Radio,

- Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris,

- Fethullah Gulen Website,

- Houghton Mifflin Company,

- Library of Congress,

- The New York Times,

- Princeton University Press,

- University of California Press, and

- Yale University Library: Near Eastern Collection.

This teaching module was originally developed for the Children & Youth in History project.