Short Teaching Module: History of the Pacific Ocean

Overview

Scholars of Pacific history explore how people build lives dependent on the ocean, how maritime connections create communities, and how humans and the environment shape each other. As a subfield of oceanic history, the Pacific offers a particularly rich setting for studying intersections between the local and global, and for charting postcolonial futures. In this essay, Sean Fraga lays out the Pacific Ocean’s major geographies and shows how Pacific approaches can send us on new voyages.

Essay

The Pacific Ocean is enormous. It touches five continents, contains 25,000 islands, and covers a larger area than all the land on Earth combined. How can historians best understand this vast region, its peoples, and its stories? While contemporary Pacific historiographies emerged from several different academic traditions, scholars studying the Pacific often adopt similar methodological approaches, drawing on diverse sources to investigate the expansive circulations and deep histories—what the Chamoru poet Craig Santos Perez calls "our migrant routes/& submarine roots"— that intertwine through the ocean’s history.

For decades, scholars have used oceans and seas to transcend national or regional containers. Fernand Braudel’s 1949 The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Phillip II showed how, over centuries, the Mediterranean Sea connected rather than divided European, North African, and Middle Eastern lands surrounding it. Scholars have usefully adapted Braudel’s connective framework to understand East Asian seas and the Indian and Atlantic oceans, seeing each as a basin facilitating the circulation and exchange of people, ideas, money, commodities, and germs. The Atlantic Ocean, for example, was shaped by centuries of intercontinental exchanges, colonization projects, and migrations, particularly the forced movements of enslaved people. These links—around, across, and within the ocean—served to create a connected Atlantic World, albeit one often bound together by force and violence.

But the Pacific is different. Its sheer size and diverse histories make a unitary "Pacific World" approach untenable. David Igler notes that this phrase ignores the ocean’s "multiplicity of seas and cultural systems," and instead "reflects the extent to which European and American outsiders rationalized the ocean—as one Pacific Ocean."1 Instead, Pacific scholars embrace multiple overlapping Pacific Worlds, each with diverse histories and linkages. Scholars have tended to focus on two major geographies, connected yet distinct.

First is the island Pacific, the ocean’s heart. This encompasses three broad cultural areas: Micronesia (roughly from Palau east to Kiribati), Melanesia (from New Guinea east to Fiji), and Polynesia (formed by the triangle between Aotearoa/New Zealand, Hawaiʻi, and Rapa Nui/Easter Island). Together with Australasia, these form Oceania. Human maritime migrations out of Asia to settle these islands started at least 35,000 years ago, with voyagers reaching the eastern-most islands about 800 years ago. "In what is the major theme of Pacific history," writes Damon Salesa, "Pacific peoples were voyaging earlier, and much further than anyone else."2 Amid decolonization in the 1960s, scholars writing from Oceania articulated a postcolonial scholarly agenda centered on the islands and their peoples.3 Today, political, economic, cultural, and kinship ties continue to link islanders to each other and to the wider world.

Second is the Pacific Rim. Although the phrase itself is recent, originating in the late twentieth century, it evokes a longer history of European imperialism in the Pacific, which initially concentrated on the ocean’s shores.4 Transpacific connections define this geography. Starting in the late fifteenth century, European nations sought new maritime trade routes with Asia, especially China.5 In the nineteenth century, steam power accelerated flows of people, capital, and goods across the Pacific Ocean, deepening links between long-established Asian polities and settler societies in the Americas and Australasia, while often bypassing Pacific islands.6 Scholars writing from the rim tend to position national histories in a Pacific context—in the ocean but not quite of it—and the field continues to grapple with how a transpacific framework, in Lisa Yoneyama’s words, "inherits problematic cartographic legacies of militarized global capitalism and its political rationality that have long vacated the people and histories of the Pacific Islands."7

Across these geographies, three primary approaches characterize Pacific histories. First is a focus on connections, circulation, and exchange. Epeli Hauʻofa, the influential Tongan and Fijian scholar, sees the Pacific not as "islands in a sea," separated by waters between them, but as a "sea of islands," full of places connected by the ocean.8 Scholars have adopted this archipelagic approach with productive results.. Second is a desire to trace these connections between geographic scales of analysis. Matt Matsuda describes this "trans-localism" as investigating "specific linked places" across the Pacific "where direct engagements took place […] tied to histories dependent on the ocean." Trans-local stories, Matsuda argues, "take on full meanings only when linked to other stories and places."9 Third is a curiosity about how the Pacific’s environments (terrestrial, coastal, oceanic); natural forces (winds, waves, weather, earthquakes); and more-than-human inhabitants (including fish, marine mammals, seabirds, and plants) have shaped (and been shaped by) human goals and decisions.

Individually and in combination, these approaches offer different entry points to Pacific Worlds. The beach and the ship both loom large in Pacific scholarship as sites where the local and global converge, and attention to linkages between geographic scales often leads scholars to what Alison Bashford describes as terraqueous places, where land and water meet—shorelines, reefs, coasts; vessels, harbors, wharves.10 As Igler summarizes, Pacific methods broadly emphasize "an oceanic rather than terrestrial approach, a peopled rather than a vacant waterscape, a place of movement and transits, and a methodology that searches for the vital interplay between global, oceanic, and local scales of history."11 In short: Start with people and follow them through the waters.

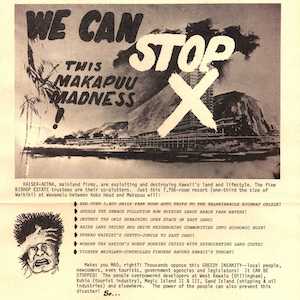

To tell these stories, Pacific scholars engage with diverse sources. Native Pacific Islanders have long carried and communicated their histories, Matsuda writes, "through ritual, image, dance, and oral tradition." Initially seen as timeless by Western anthropologists, scholars have come to recognize these as "categorical forms of historical knowledge production," socially constructed and culturally dynamic.12 Broadly, scholarly interest in non-archival and non-textual sources extends to archeological investigations, ethnographic evidence, material cultures, and visual representations, to name a few. Pacific historians often leverage these kinds of sources to reassess and complicate European and American imperial and colonial records. Perspective and positionality also informs authorship. Many Pacific scholars link oceanic histories with postcolonial futures by integrating academic work into political and creative practices, and non-Native scholars often find collaborations with Native communities fruitful (if sometimes fraught).

Ultimately, while the Pacific Ocean’s scale can seem intimidating, its vastness also offers myriad opportunities to plot one’s own scholarly voyage—to plunge deep into the waters and carry fresh insights toward shore.

1David Igler, The Great Ocean: Pacific Worlds from Captain Cook to the Gold Rush (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 10–11

2Damon Salesa, "The Pacific in Indigenous Time," in Pacific Histories: Ocean, Land, People, ed. David Armitage and Alison Bashford (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 32–35. The '-nesia' divisions, originally racialized names created by Europeans, have since been adopted by islanders themselves. Salesa, "The Pacific in Indigenous Time," 32.

3David Armitage and Alison Bashford, "Introduction: The Pacific and its Histories," in Pacific Histories: Ocean, Land, People, ed. David Armitage and Alison Bashford (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 12–13.

4 Bruce Cumings, "Rimspeak; or, the Discourse of the 'Pacific Rim,'" in What is in a Rim?: Critical Perspectives on the Pacific Region Idea, ed. Arif Dirlik (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1993).

5Joyce Chaplin, "The Pacific before Empire, c.1500–1800" in Pacific Histories: Ocean, Land, People, ed. David Armitage and Alison Bashford (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014): 53–74.

6Sean Fraga, "'An Outlet to the Western Sea': Puget Sound, Terraqueous Mobility, and Northern Pacific Railroad’s Pursuit of Trade with Asia, 1864–1892," Western Historical Quarterly 51, no. 4 (Winter 2020): 439–458, DOI:10.1093/whq/whaa114. Frances Steel, Oceania under Steam: Sea Transport and the Cultures of Colonialism, c.1870–1914 (Manchester, U.K.: Manchester University Press, 2017.

7Armitage and Bashford, "Introduction," 11–13. Lisa Yoneyama, "Toward a Decolonial Genealogy of the Transpacific," American Quarterly 69, no. 3 (Sept. 2017): 471-482. DOI:10.1353/aq.2017.0041

8Epeli Hauʻofa, "Our Sea of Islands," The Contemporary Pacific 6 no. 1 (Spring 1994): 148–161.

9Matt K. Matsuda, Pacific Worlds: A History of Seas, Peoples, and Cultures (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 5.

10Alison Bashford, "Terraqueous Histories," The Historical Journal 60, no. 2 (June 2017): 253–272. doi:10.1017/S0018246X16000431.

11Igler, Great Ocean, 11.

12Matt K. Matsuda, "The Pacific," American Historical Review 111 no. 3 (June 2006), 764.

Primary Sources

Credits

Sean Fraga is a historian of the North American West and eastern Pacific Ocean. He is currently a Mellon postdoctoral fellow with the Humanities in a Digital World program at the University of Southern California. His book project, Ocean Fever: Steam Power, Transpacific Trade, and American Colonization of Puget Sound, is under contract with Yale University Press, and his research has been published in Western Historical Quarterly and Current Research in Digital History. He holds a B.A. in American Studies from Yale and an M.A. and Ph.D., both in history, from Princeton.