"We can stop this Makapuu madness!"

Annotation

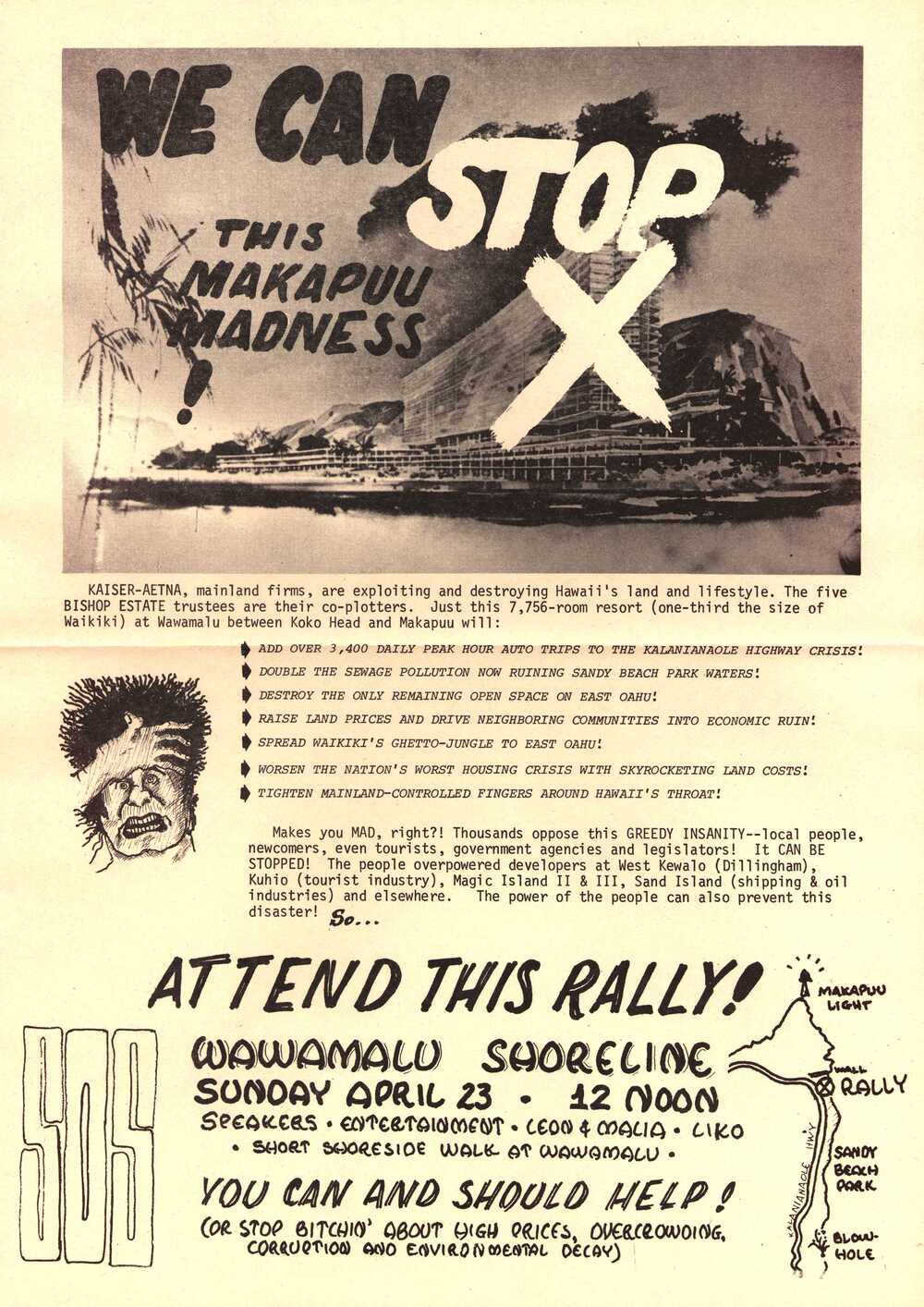

After World War II, the rise of jet travel and mass tourism brought new visitors—and new pressures—to many places within the Pacific Ocean. Hawaiʻi is a prime example of how tourism-driven development and activist responses have shaped local environments. This flyer, created by the grassroots environmental organization Save Our Surf, mobilized community opposition to resort construction at Awāwamalu, also known as Wāwāmalu Beach or Sandy Beach, at Oahu’s southeastern corner.

Native Hawaiians recount how Pele, deity of fire and volcanoes, created Oahu and the other Hawaiian islands by digging into the earth as she moved from east to west. On Oahu, Pele dug first at Leʻahi, or Diamond Head, midway between Awāwamalu and Honolulu, Oahu’s largest city. For nineteenth-century sailing ships, the Pacific Ocean’s prevailing winds and currents encouraged voyages via Hawaiʻi, and Honolulu emerged as a central, convenient supply point—a primary reason the United States annexed the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in the late nineteenth century. After World War II and the establishment of Hawaiian statehood in 1959, the Hawaiian islands increasingly became a leisure destination, drawing tourists and outside investment from Japan and the mainland United States.

But resort construction frequently involved privatizing and industrializing the coastline, and upset residents pushed back. In 1964, John Kelly, a white mainlander who grew up in Honolulu, founded Save Our Surf. "Hawaiʻi’s shoreline—the habitat of many people—was under assault," he later wrote. Surfing, invented by Native Hawaiians and later enthusiastically adopted by outsiders, became a way to unite island residents and cultivate widespread support for coastal protection.

In the early 1970s, mainland developers proposed building a 7,700-room resort at Awāwamalu. Save Our Surf argued that this development would dramatically increase traffic and pollution, raise housing prices, and "destroy the only remaining open space on east Oahu." The rally was just the start. After more than four decades of sustained community organizing, court battles over rezoning and ballot initiatives, and multiple additional development attempts, the State of Hawaii reclassified this shoreline as conservation land. Since 2017, Awāwamalu has been part of the Ka Iwi Coast, a seven-mile stretch of coastline preserved in perpetuity for public benefit. But dependence on tourism continues to roil Hawaiʻi—most recently during the COVID-19 pandemic, when locals worried that irresponsible visitors would spread disease and strain hospitals—and environmental activism remains an important part of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. Across the Pacific Ocean, tensions over access, use, and benefit continue to structure human engagement with coastal environments.

This source is part of the History of the Pacific Ocean teaching module.

Credits

Kelly, John, “We can stop this Makapuu madness!,” UHM Library Digital Image Collections, accessed March 29, 2022, https://digital.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/show/31351.