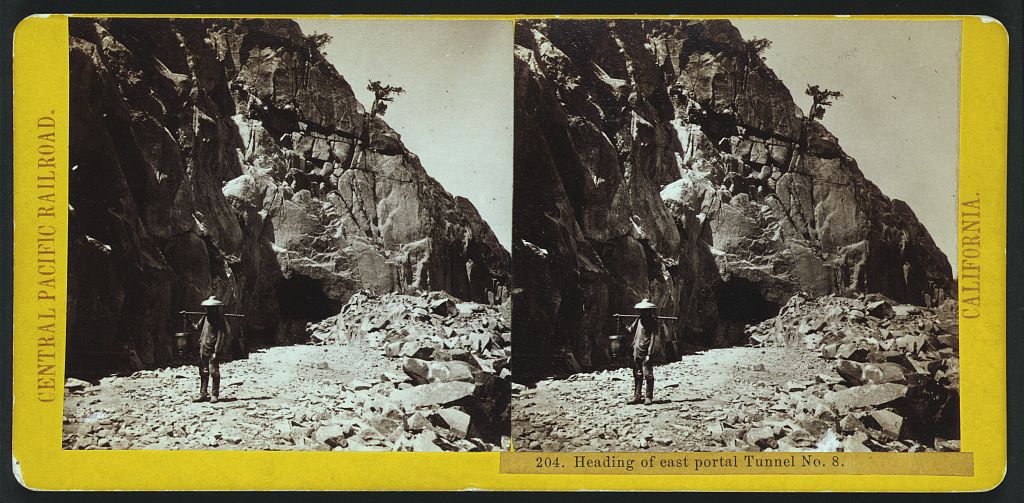

Heading of east portal Tunnel No. 8

Annotation

In the late nineteenth century, multiple transcontinental railroads were built across the United States and Canada. These were Pacific projects twice over: Each railroad aimed to open new routes for global trade with Asia, and each depended heavily on Asian laborers for their construction. This photograph, taken by Central Pacific Railroad’s official photographer, shows a Chinese railroad worker near the mouth of a tunnel, carrying tools or debris on a shoulder pole.

Central Pacific, completed in 1869, built the western half of the first North American transcontinental railroad and relied on a construction workforce that was about 90% Chinese, employing roughly twenty thousand Chinese men. These men came largely from Guangdong province in southern China. Poverty and instability pushed many to seek employment abroad, and nearby Hong Kong provided an easy transpacific portal to North America. The next several North American railroads—including Northern Pacific, Southern Pacific, and Canadian Pacific—similarly relied heavily on workers from China (and later Japan) for their construction.

These men undertook grueling and dangerous work. Chinese workers carved fifteen tunnels for the Central Pacific through the Sierra Nevada Mountains with chisels and blasting powder, carrying debris away in buckets. Many died: At least twelve hundred Chinese workers were killed while building the Central Pacific.

But the railroads’ dependence on Chinese workers coexisted uncomfortably with racist fears in the United States and Canada that Chinese migrants would undercut white workers’ wages. These anxieties grew only more acute as Chinese migrants finished railroad construction and found other work. Less than fifteen years after the first transcontinental railroad was completed, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act severely curtailed Chinese immigration to the United States; three years later, Canada similarly limited Chinese immigration.

Except for the rails and tunnels these workers built, they left few direct records. Payroll books and documentary photographs, like this one, record their presence and testify to their labor. But these sources tend to lack specific details about the men themselves, treating them as abstractions, as little more than productive hands. Understanding these men as people—how they lived while in the United States, the communities they formed, what they made of their experiences—is more difficult. Scholars have recently turned to archaeological evidence and family oral histories to more fully reconstruct Chinese railroad workers’ lives and stories.

This source is part of the History of the Pacific Ocean teaching module.

Credits

Hart, Alfred A. Heading of east portal Tunnel No. 8, Library of Congress

https://www.loc.gov/item/2005682948/