Source Collection: Legacies of the Revolution

Overview

The powerful influence of the French Revolution can be traced in the reactions of those who witnessed the event firsthand and in the strong emotions it has aroused ever since. For some, the French Revolution was a beacon of light that gave a world dominated by aristocratic privilege and monarchical tyranny a hope of freedom. Nineteenth-century revolutionaries and nationalists frequently harkened back to the days of 1789, sometimes even taking up the names, terms, colors, and rituals of the original French Revolution. Twentieth-century revolutionaries looked to 1789 as a kind of template for revolutionary events. If Robespierre could come on the heels of Lafayette and he, in turn, could give way to Napoleon, then might modern revolutions inevitably follow a similar scripted path, toward authoritarianism? Did revolutions always begin with hope and enthusiasm only to turn violently radical and then permit an authoritarian, even dictatorial figure, to seize power? Were revolutions like some sort of political fever, with distinct symptoms? Scholars and political activists continue to argue these questions. Yet no matter what their interpretation, the lessons and impact of the Revolution continue to be at the heart of several different historical and contemporary political debates.

This source collection consists of 41 primary sources.

Essay

Part I: Contemporary Reactions to the French Revolution

The events of the French Revolution alternately energized and repulsed contemporaries. Many experienced what English poet William Wordsworth immortalized in his poem French Revolution As It Appears to Enthusiasts (1804; also in Prelude): "Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive/ But to be young was very heaven!" The French overthrow of the old regime and all it stood for was celebrated and commemorated in songs, engravings, poems, paintings, and music. Some, like Wordsworth, even voyaged to France to see events firsthand. Yet from the first months of the Revolution, others saw a darker side of the unfolding drama. The first major debate about the French Revolution outside of France was sparked by a lively polemical tract written by Edmund Burke just months after the fall of the Bastille. A member of the British Parliament, Burke had gained a reputation defending the Americans in their revolt against the British crown. He was much less favorably impressed by the French Revolution, however. In Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), he expressed reservations about the revolutionaries' reliance on reason as the sole standard of government and predicted, quite presciently it turned out, that the French would eventually turn to violence to enforce their decisions. Burke went beyond criticizing the French revolutionaries; he offered the first systematic defense of "conservative" principles, arguing that gradual change and a kind of organic continuity in society stretching across the generations were preferable to violent, rapid upheavals in the structure of government. From its very beginning then, the French Revolution stimulated profound political controversy and equally profound rethinking of the nature of government itself. Because the revolutionaries aimed to rebuild government from the foundation upward, substituting reason for tradition and equal rights for privilege, they inevitably provoked wide-ranging reactions.

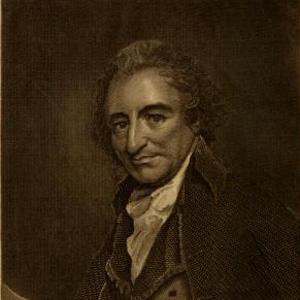

Burke's attack set off a firestorm of protest within Great Britain. His passing reference to the lower classes as "the swinish multitude" got him swift responses, with titles such as "Hog's Wash" and "Pig's Meat" and an "Address to the Hon. Edmund Burke from the Swinish Multitude." The most effective response was that of Thomas Paine, the English author of the famous defense of the American cause, Common Sense (1776). Paine's Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr. Burke's Attack on the French Revolution (1791 and 1792) laid out a cogent defense of the use of reason in remaking the forms of government. Paine insisted that good government depended on establishing a constitution that guaranteed the natural rights of all men. In his view, Great Britain did not have a constitution; it had only a long history of fraudulent monarchical and aristocratic claims guaranteed by force. By 1793 Paine's attack on the English social and political establishment had sold some 200,000 copies, more than any other political polemic in English history. Paine's prestige became so great that he was elected to the National Convention despite the fact that he did not speak French.

Burke's tract also provoked one of the first sustained feminist arguments in world history in Mary Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792). (Document 3) Wollstonecraft's pronouncement that women should be educated like men in order to become virtuous citizens created instant controversy. One critic declared that her works would be read "with disgust by every female who has any pretensions to delicacy; with detestation by every one attached to the interests of religion and morality" (Miriam Brody, ed., Mary Wollstonecraft, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, [London: Penguin Books, 1992], 2, citing the Historical Magazine, [1799], 1:34). If her arguments for women's rights seem relatively tame to present-day readers, then that is probably a good measure of the impact on the modern world of French Revolutionary feminists.

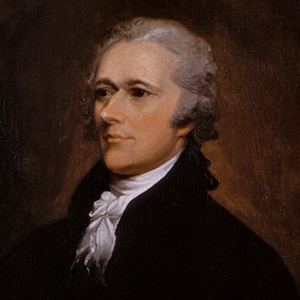

North Americans followed the French Revolution with special interest. Americans believed that the events of 1789 drew heavily on their own experience. The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen seemed to borrow strikingly from the states' bill of rights. Even more direct influence took place when Thomas Jefferson, resident in France at this time, passed along specific ideas to the legislators through the Marquis de Lafayette. Although the French Revolution took a far different path than the North American variety, this interaction was close, so it is not surprising that the initial U.S. reaction to the Revolution was positive. Virtually the only dissenting voice among the leading American politicians was that of John Adams who, like Burke, expressed his reservations early. Indeed, throughout the revolutionary decade, the Republican Party, led by Jefferson, remained generally favorable, although the Terror did inspire some wavering. Others, however, became opposed, especially the Federalists. Despite its declining influence in American politics, this party carried the day with regard to U.S. policy toward France. Conflict over land and borders between these two ostensibly friendly nations would sour many Americans on France and its revolution by the late years of the revolutionary decade.

Philosophers, poets, and novelists felt compelled to comment on the French Revolution as much as politicians. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant followed events with interest, sometimes enthusiasm, but also with worry. As his treatises show, he appreciated the deep power of the notion of right. The French aristocrat François-René Chateaubriand took a more negative view. In his Historical, Political and Moral Essay on Revolutions, Ancient and Modern, he denounced the Jacobins as "infuriated men" who had erected "a thousand sanguinary guillotines" in all the villages and towns of France. The German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel used the course of the French Revolution to develop his notions about the essential, inner meaning of history. Such use of the Revolution as a springboard for philosophical and political inquiry marked the degree to which contemporaries viewed this event as both a turning point and as a break with older ways of doing things.

Part II: Revolutionary Legacies in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

Since the beginning of the nineteenth century the legacy of the French Revolution has been hotly debated by politicians, revolutionaries, and political theorists. The Revolution of 1789 gave birth to what soon came to be called "ideologies," a word that was first used during the French Revolution. An ideology is a defined doctrine about the best form of social and political organization. Before 1789, most people (the Americans of the new United States were the great exception) lived with the general form of government their ancestors had known for centuries, and by and large this meant hereditary monarchy. After 1789, no form of government could be accepted as legitimate without justification. The revolutionaries had established a republic, so from the foundation of the republic in 1792 onward, at the very least, republicans would challenge monarchists. Among republicans, some preferred a government directed by the elite, whereas others, known as democratic republicans, advocated a more democratic structure. Many other self-conscious ideological alternatives arose during this era—nationalism, liberalism, socialism, and eventually communism—all as a result of, or in reaction to, the French Revolution. Only conservatism stood opposed, arguing that all of these doctrines of social or political change were dangerous innovations.

Modern nationalism began in France during the revolutionary decade and was spread by revolutionary and Napoleonic armies to the rest of Europe. Many Europeans adopted this idea because nationalism defended the right of a nation to resist French control. After the fall of Napoleon and the remaking of European boundaries at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, nationalists turned their ire on foreign rulers: the Austrians in Italy, the Russians in Poland, and so on. From Derry (Northern Ireland) to Danang (Vietnam) and from Helsinki to the Cape of Good Hope, this struggle for national liberation became one of the most important themes of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European and world politics.

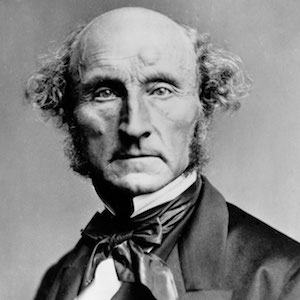

Nationalists hoping for their own nation-state might favor either a monarchy or a republic. Among republicans, they might be either socialists or liberals. The Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini took the left-wing nationalist position; he believed that nationalism should be revolutionary and allied with projects to defend the interests of the poor. Others, such as the "utopian socialist" Charles Fourier, wanted to keep the revolutionary legacy of social reform but limit the violence that was increasingly associated with the "Reign of Terror" of 1793–94. This same violence repelled other generally favorable nineteenth-century commentators such as the philosopher John Stuart Mill and the historian and politician Alexis de Tocqueville, who preferred a more elitist approach to any reform of the structure of government.

Not only did the Revolution spawn many beliefs that further extended its logic, but as Hegel surmised, it also created reactions against it. Even before 1789, the "anti-philosophes" had decried Enlightenment thinking. Burke and others quickly denounced the Revolution itself, particularly the potential for violence. The next two centuries would witness the rise of a powerful and diverse group of detractors. Even Hippolyte Taine, holding a chair in the history of the French Revolution at the Sorbonne and a defender of the legacy of freedom he saw emanating from the Revolution, considered the event as a whole monstrous.

Many French who opposed the French Revolution did so because of their religious beliefs. Although the Revolution had instigated a degree of religious oppression, it also permitted an uneasy truce with the churches. The fundamental secularism of the revolutionary project offended those who preferred that state power be dependent on religious authority. Typical of these critics was Joseph de Maistre, an aristocratic writer and philosopher who condemned the Revolution as fundamentally evil and impious. In the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, conservatives also linked the French Revolution to what they saw as the negative aspects of democracy and mass politics. Gustave Le Bon, an influential theorist of "crowd" behavior, warned that the French Revolution epitomized the irrationality, savagery, and violence of the mob. Some conservatives went even further, decrying the universal principles of human rights upon which the Revolution was based. Critics saw danger in these universal appeals, especially as they promised to open first France and then the world to social equality for Jews and for immigrants. The "cosmopolitan" form of thinking, so they alleged, ate away at the fibers knitting together the French people and violated the deep roots of moral strength of France vested in its people. These two commitments—religion and nativism—had separable chronologies, but became increasingly linked as some individuals, such as Charles Maurras, leader of the right-wing organization Action française, insisted that France must become, or return to being, more devout and more nationalistic. For such critics, the legacy of the French Revolution was almost wholly negative.

Socialists and communists had a more positive view of the French Revolution: they considered it an important harbinger of the future. However, they wanted to go beyond its tentative promises of individual rights and legal change within a constitutional order. Socialists and communists believed that the French Revolution had not gone far enough. The founders of communism as an international movement, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, both commented extensively on the French Revolution, hoping to find in those events important lessons for the future course not only of communism but of history itself.

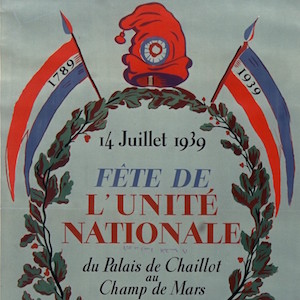

Interest in the French Revolution was especially intense at the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. In 1889 France's Third Republic celebrated the centennial of the French Revolution with the building of the Eiffel Tower. Arguments about revolutionary events continued to be heated, especially because ü had broken out again in France in 1830, 1848, and 1870–71. The latter revolution, associated with the Paris Commune, was especially violent; as many as 20,000 people died in street fighting in 1871 when the new republican government sent its army to disband the revolutionary commune (city government) of Paris. Because of the continuing cycle of revolutions in France and the promise of a worldwide revolution through communism, memories of the original French Revolution of 1789 continued to haunt the writings of important socialists, anarchists, and communist revolutionaries.

The French Revolution clearly had repercussions throughout the world. For example, the Napoleonic occupation of Spain in 1808 was the spark that ignited the independence movement in Latin America. Beginning with Mexico in 1810, Central and South American local elites declared their independence from Spain and Portugal. Most countries achieved independence in the 1820s. Others, like the revolutionary Simon Bolívar, rejected the control of these elites, preferring to follow the example of Haiti. The spread of nationalism to Latin America was accompanied by some of the other liberal ideas associated with the French Revolution, but not by all.

Twentieth-century revolutionaries in east Asia were interested not only in the potent ideology of nationalism, but also in the transformative power of revolutions on both society and the state. Exposed early to the model of the French Revolution, those espousing revolutionary change in China and Vietnam made the French Revolution of 1789 topical in a new part of the world.

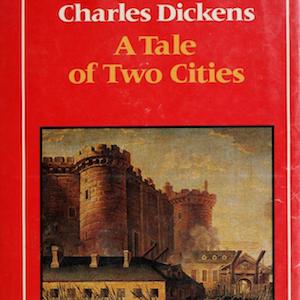

Outside the realm of politics, the allure of the Revolution remained important, not only for those who wished to comment on contemporary events but also for the innate drama and pathos of many revolutionary events. Alexis de Tocqueville observed, "What remains most alive in the original spirit of the Revolution is in . . . literature. . . . [T]he only Frenchmen who today can be connected by a kind of esprit de corps to their fathers are the men of letters" (Roger Boesche, ed., Alexis de Tocqueville: Selected Letters on Politics and Society, trans. James Toupin and Roger Boesche [Berkeley, 1985], 329). Some of the giants of nineteenth-century European literature wrote about the French Revolution, including Honoré de Balzac, Charles Dickens, Victor Hugo, and Anatole France. These literary treatments kept the people, the events, and the ideas of the Revolution alive for generations. In the twentieth century, the powerful imagery and impact of the Revolution made it an ideal candidate for the cinema. Some of the greatest films in French cinematic history have focused on the revolutionary period. From Abel Gance's Napoleon in 1927 to Andrezj Wajda's Danton in 1984, directors have grappled with the meaning of the events of the French Revolution. The frequent twentieth-century remakes of films about the Scarlet Pimpernel demonstrate that the allure of the Revolution remains alive and well in the English-speaking world too.

Has the importance of the French Revolution now faded? In some ways, it has simply shifted. Scholars continue to be interested in the causes, course, and legacy of the French Revolution, but they have a wider view of it: not only do they seek its meaning in a broader range of events and activities, in the traditional arenas of diplomacy and high politics as well as in the newer ones of festivals, symbols, engravings, and songs. They also seek its significance in many more places, from Haiti and the other French colonies to Egypt, Russia, and wherever the French armies marched, indeed, to wherever the message of the Revolution was heard.

Even before the Revolution had ended, before the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, enterprising artists and printers had begun to publish collections of engravings that recounted the principal events of the French Revolution for subscribers. Revolutionary governments aimed to spread their message through propaganda, and they left no item of everyday life untouched in their efforts to spread the gospel of revolution.

Memories of the French Revolution of 1789 are not only historical in nature, but also constitute a living legacy. They are found in places, images, and objects. A few liberty trees still stand today, usually large oaks on the village square. Many people kept mementos of the Revolution, whether engravings, ribbons (in the form of cockades), crockery, even bits of the stones of the Bastille prison. Songs continued in popular memory. The sheer weight of these memories can be measured by the very large number of objects and images still in existence. The Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris houses some 30,000 engravings from the time of the French Revolution. Libraries in the United States have many thousands of them too. Museums all over France have material collections of crockery, ribbons, flags, swords, and clothing, all of which could serve as emblems of revolution—or counterrevolution. The Museum of the French Revolution in Vizille, France, has the most systematic and extensive of these collections, which we can only sample here.

Primary Sources

Credits

From LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION, https://revolution.chnm.org/exhibits/show/liberty--equality--fraternity/legacies-of-the-revolution