Long Teaching Module: Children’s Health in Early Modern England

Overview

Children and youth in early modern England (1500-1800) were subject to many diseases and physical hardships. From the great epidemic diseases of bubonic plague and smallpox, to more common illnesses such as measles and influenza that still afflict children today, sickness put children and youth at great risk. With no knowledge of bacteria or antibiotics, and surgery performed without anesthesia or even hand washing, there were few remedies for childhood illnesses beyond a nourishing diet and keeping the patient warm. Even surviving an illness could have permanent consequences, for example, scarlet fever left many children blind and deaf, and measles could cause severe scarring and facial bone loss. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, potential adaptations, and essay prompts relating to the eleven primary sources.

Essay

Introduction

Children and youth in early modern England (1500-1800) were subject to many diseases and physical hardships. From the great epidemic diseases of bubonic plague and smallpox, to more common illnesses such as measles and influenza that still afflict children today, sickness put children and youth at great risk. With no knowledge of bacteria or antibiotics, and surgery performed without anesthesia or even hand washing, there were few remedies for childhood illnesses beyond a nourishing diet and keeping the patient warm. Even surviving an illness could have permanent consequences, for example, scarlet fever left many children blind and deaf, and measles could cause severe scarring and facial bone loss.

One measurement of health in early modern England is revealed in the statistics of the number of deaths kept by church parishes. From these records historians have gleaned that infant mortality (death during the first year of life) was approximately 140 out of 1000 live births. The average mother had 7-8 live births over 15 years. Unidentifiable fevers, and the following list of diseases, killed perhaps 30% of England's children before the age of 15 – the bloody flux (dysentery), scarlatina (scarlet fever), whooping cough, influenza, smallpox, and pneumonia.

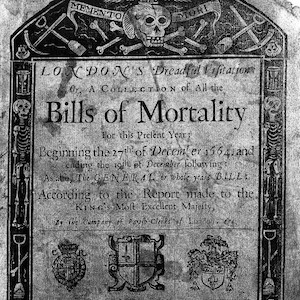

Death from disease was higher in urban than in rural areas. Early modern cities were widely, and often rightly, regarded as deadly environments. They contained large concentrations of population who were often poorly fed and housed. "Crowd diseases" such as typhus, smallpox, and tuberculosis prospered, and bubonic plague epidemics periodically swept through dense urban populations. In 1563, 1603, 1625 and 1665, about one fifth of the population of London died in plague outbreaks. In 1665, one of the deadliest years, 80,000 people died in the capital city. Of this number, historians estimate that at least 45,000 of the victims were under the age of 15.

Besides diseases, accidents were common sources of sickness, disability and death for children and youth. From surveys of coroners's inquests, drowning in wells and bathtubs, was the most reported accidental death in children under the age of 5. Accidents were also reported connected to the work in which children were engaged beginning around age 8. Children cracked their skulls while fetching water, were trampled by horses while ploughing, or dropped and injured while under the care of siblings. Boys, unless they were from the noblest of families, were expected to serve an apprenticeship. They were often placed in dangerous crafts such as tanning, blacksmithing, or serving on ships, where chemical poisonings, fires, and war injuries were frequent occurrences. There are also accounts in diaries of the period of youthful pranks leading to injury, for example, hiding gunpowder in candles so they blew up when lit.

Throughout this period the primary place where sick children and youth were cared for was in the home, and the principal healers were women – mothers, daughters, wives, and servants. Powder burn remedies —applying a mixture of poultry fat and dung—were commonly included in home receit (remedy/recipe) books kept by the mistress of the household. Women developed considerable professional knowledge after the rise of the printing press in 1500 and the publication of books that had been only in the hands of physicians. Both herbal and chemical medicines were described as suitable for the young in family receit books, such as dried dill in honey for a cough, and iron filings in beer for paleness of the skin.

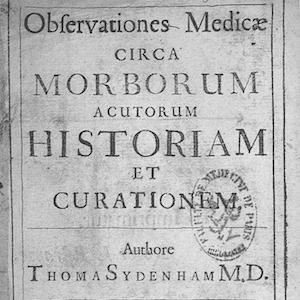

Children were rarely treated by the small and expensive elite of university-trained physicians to whom adult patients turned for a prognosis and not for a cure. Their remedies were also considered too drastic for children as they largely consisted of rectal purging (laxatives), bloodletting (cutting a vein open with a lancet), and forced vomiting (emetics). These treatments were based on an ancient Greek medical theory that the body was composed of four substances, or humors, created from the digestion of food. The four humors were choler or yellow bile, phlegm or mucus, black bile, and blood, and all had properties of being hot/cold and dry/wet. If the humors were balanced – neither too strong nor too weak – you were healthy. The hot and wet humor of blood and the hot and dry humor of yellow bile were believed to be naturally stronger in the young. Occasionally if these humors were not weakened and released from the body in the form of sweat, tears, urine, feces, or even sneezing, physicians would give children emetics to make them vomit or let blood through "cupping." Heated glass, bone, or brass cups would be placed upon skin that had been scratched or scarified with a knife. Blood would then flow gently from these wounds due to the creation of a vacuum by the heated cup.

Worried parents consulted surgeons, trained through apprenticeship, for broken limbs, ruptures, and the bladder stone. The latter was caused by the early modern diet, which was rich in gravel. Boys were often operated on for the stone by surgeons in this period with a mortality rate of 30%. The operation was called a lithotomy and took about three to five minutes to perform. No anesthesia was used, instead surgeons relied on the child fainting from pain and being out during the extraction of the stone. Most often, parents turned first to family, friends, and neighbors, for medical advice, even the local blacksmith for a fee would set bones in humans as well as animals. As the specialty of pediatrics (from the Greek for child and healing) had yet to emerge, children were treated as small adults in hospitals and kept in the same wards as adult men and women. Some charitable institutions were opened in the early modern period, for example, the Children's Hospital in Norwich in 1621, but they tended to be more for children who were abandoned by their parents or orphaned, than for sick youngsters. The largest institution for orphans was the Foundling Hospital in London, opened in 1741. There were also medical discoveries that helped children and youth in this period, most notably, inoculation and vaccination for smallpox.

Starting in the 1960s several scholars have argued that early modern parents tried not to invest too much emotion (or money) in a child until it reached an age where survival was likely. High birth rates, accompanied by high death rates for children under the age of ten years old, meant that family life was fragile and uncertain. Yet the parent-child relationship seems to have been as strong in the early modern period as in any other age, and former ideas of emotional indifference before the eighteenth century are now widely questioned by scholars. Most of the population had a hard struggle for existence but children were cared for as much as conditions would allow. The harrowing grief of mothers and fathers who lost children to disease or accident is indeed all too apparent in diaries and letters of the period.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

I have found that the best way to teach about sickness and health from centuries ago is to not to focus on the biology and statistics of diseases but to focus on the suffering and the impact of illness on a person's life. I have had students write about their own experience of illness until the age of 18, and then had them compare and contrast that with the common illnesses a child and youth would have experienced in early modern England. Students have also researched how medical conditions of children and youth would be diagnosed and treated by a variety of healers. They took into consideration wealth and poverty, class status, gender, and whether they were living in a city or in the countryside. Finally, I have had success with using visuals to illustrate not just medical care and treatment but environmental conditions. If you have students imagine life without modern conveniences such as electricity, gas, sewers, clean water, cars, and so forth (the list is long), their understanding and interpretation of images of early modern children and youth grows as they take into account the context of health, hygiene, and illness.

Discussion Questions

- What were the common illnesses of children and youth in early modern England? What remedies were suggested and by whom? Can you describe some of the changes in medical treatment during this period? (Classification and description of diseases, inoculation and vaccination).

- Some historians have argued that children and youth had a miserable existence and that parents in early modern England tried not to become too attached to their children, as infant and child mortality was so high. Can you use the sources to argue for and against this thesis? (Teeth pulling, Gin Lane, Infanticide Trial versus The Graham Children and the Evelyn Diary).

Lesson Plan

Time Estimated: three 45-minute classes

Objectives

- Students will be able to identify possible connections between the lack of modern conveniences and health, hygiene, and illness among children in early modern England.

- Students will be able to debate the extent to which parents demonstrated attachment to children in a period of high mortality for infants and young children.

Materials

- Printouts of primary sources sufficient for each student to have a full set of the texts and images in the Health in England Teaching Module. 1

- Highlighters

- Index cards

Day One

Hook

Ask students to imagine life without modern conveniences such as electricity, sewers, and clean water by listing ten possible effects on health, hygiene, and illness. Then, with a partner, have them predict which of those effects were common among children in early modern England. Make a class list of these predictions to post for comparison later.

Activity

Students will read the primary sources looking for any connections between the lack of modern conveniences and health, hygiene, and illness among children. One strategy to help with close reading is to help the students generate lists of typical words they might find in the text, and then encouraging them to underline or highlight the words associated with a lack of conveniences (such as lack of clean water for drinking or washing) and circle or highlight the words associated with symptoms of illness (complexion, fever, fits, pain, sweat, swollen, shivers, blisters) and treatments (ointment, medicine, bloodletting, fasting, bed rest). Have the students turn in their annotated sources. Check to make sure they found most of the key words. If not, show them to the students the next day.

Day Two: Debate Prep

Return the annotated sources and ask students to share with a partner the words that appeared the most often.

With partners, have students try to translate those words into lists:

- identifying the common illnesses of children and youth in early modern England and

- identifying the remedies suggested and by whom.

They should write these analyses of the sources in the margins.

Students prepare for a debate on whether parents in early modern England tried not to become too attached to their children, as infant and child mortality was so high.

Day Three: The Debate

Debate Directions

Divide the class into two groups (pro and con).

Assign each student a specific speaking role in the debate.

- Each group has a different student make the opening statement and the closing statement.

- Each group has six main pieces of evidence delivered by six different students.

- Each group also assigns six students to critique the evidence delivered on the basis of the authority or reliability and perspective of the source.

- That's 28 student roles. Adjust as necessary for the size of the class. If the class is larger, assign students to critique the arguments and evidence used overall in the debate and then report on their assessment at the end.

Differentiation

Some strategies for supporting and challenging students are already included in the lesson. For struggling readers, the sources might need to be translated into modern English, and perhaps even analyzed together as a class. The preparation for the debate for students still learning how to construct and support arguments might take an extra day, so the teacher can speak individually with each student to guide the framing of the arguments and selection of evidence to support the main points. To challenge students further, it might be possible for them to find additional evidence not included in this module, even perhaps going beyond the borders of England to compare the attitudes and practices toward children's health in other places.

Document Based Question

(Suggested writing time: 50 minutes)

Directions

The following question is based on the documents included in this module. This question is designed to test your ability to work with and understand historical documents.

Drawing on specific examples from the sources in the module, write a well- organized essay of at least five paragraphs in which you answer the following question:

- To what extent did parents in early modern England try not to become too attached to their children, as infant and child mortality was so high?

- has a relevant, clear thesis that answers the question,

- uses at least six of the documents,

- analyzes the documents by grouping them in as many appropriate ways as possible. Does not simply summarize the documents individually, and

- takes into account both the sources of the documents and the creators' points of view.

Write an essay that:

You may refer to relevant historical information not mentioned in the documents.

Be sure to analyze point of view in at least three documents or images.

What additional sources, types of documents, or information would you need to have a more complete view of this topic?

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Lynda Payne, Ph.D., RN, Sirridge Missouri Endowed Professor in Medical Humanities and Bioethics and Associate Professor of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. She is the author of With Words and Knives: Learning Medical Dispassion in Early Modern England, and is currently researching and writing a monograph on the 18th-century surgeon Percivall Pott.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Sharon Cohen teaches AP World History and IB Theory of Knowledge at Springbrook High School in Maryland. She regularly presents papers on world history pedagogy at the annual conferences of the World History Association, the American Historical Association, the National Council for Teaching History, and the National Council for the Social Studies, served on the College Board's AP World History Development Committee, contributed articles to the online journal World History Connected, and published curriculum units in world history for the College Board and the online model world history project World History For Us All.

This teaching module was originally developed for the Children and Youth in History project.