Analyzing Personal Accounts

Overview

Personal accounts, including memoirs, journals, diaries, autobiographies, and life histories, are important historical sources that help us understand the human condition. These are the stories we tell about our lives that usually portray a larger picture of a life in historical context. In reading a personal account of someone far removed from your own culture and historical period, it is possible to learn about the foreign within the familiar framework of an unfolding life.

Essay

|

Personal accounts, including memoirs, journals, diaries, autobiographies, and life histories, are important historical sources that help us understand the human condition. Everybody has a personal history; every life has its share of joy and sorrow, victory and tragedy. These are the stories we tell about our lives that usually portray a larger picture of a life in historical context. In reading a personal account of someone far removed from your own culture and historical period, it is possible to learn about the foreign within the familiar framework of an unfolding life. The comparisons and contrasts between the lives of the reader and the subject inevitably spring to mind. All personal accounts imply motivation on the part of the subject. A written document implies a certain level of literacy and an attitude of self-reflection. Orally recorded accounts require a vehicle of transmission, perhaps a scholar who records interviews with an individual. Sometimes oral interviews are recorded among family members or among people who share a particular cultural value, such as Appalachian mountain musicians. Sometimes an individual makes his or her own recordings or videotaped personal accounts. Personal accounts can focus on particular events or may cover a life more completely. They sometimes involve recollections focused on extraordinary events such as participation in wars or catastrophic events, or explanations of unusual experiences. More recently, historians have begun to note everyday experiences as a measure of social order, so personal accounts can provide information on a particular “slice of life,” explaining the circumstances of coming of age experiences or the way of life in a specific region. Personal accounts have also been an integral part of oral history studies in regions that lack a legacy of written history. Many recent African histories rely on personal accounts to trace family and community connections. In every case, the personal account is highly subjective, which is the basis of both its value and limitation. Personal accounts will not always be chronological; they are more likely to jump around, as our minds do, reflecting images of a certain experience from a variety of perspectives, even within one person’s own recollections. An eyewitness account of an event or time and place is invaluable, but it is also limited to one point of view. A personal account reveals only what an individual wishes to reveal and usually presents just one side of any story. Any personal account is but one of many stories that could be told about an individual, yet it is an important one that allows us access to a range of voices and perspectives.

How do historians use personal accounts?Anthropology and other cross-cultural approaches have begun to influence the ways in which history is interpreted and various perspectives are valued. The voices of minorities have long been silent, or marginalized at best. They can often provide personal perspectives on historical events and offer insight into the past beyond official or formal sources. What we know about the past is what certain individuals have decided should be preserved. In ancient historical periods, court praise singers preserved in oral poetic form the preferred version of succession as a hedge against usurpers. More recently, as scholars write their interpretations of history and biographies of significant players, the nature of history itself is shaped by their choices. It is important to know what facts they consider significant and which individuals they choose to study. Sometimes political considerations silence certain voices. In Morocco, for example, the government has banned a book that recounts the long imprisonment of a family whose head opposed the reigning king in a coup 20 years ago. Depending on the political and socioeconomic views of the person asked, the account, published as Stolen Lives: Twenty Years in a Desert Jail, is described as “brutally honest” or “full of lies.” Personal accounts and oral histories allow scholars to delve more deeply into the complexities of human experience. These kinds of sources can bring forth the voices of people whose personal stories have long been ignored. Personal accounts can also offer comparative views on issues like public transfers of power between high profile individuals as effected in battles and political pacts, or provide an ordinary perception of a period in history, as experienced by the majority of people in the culture. Sometimes the quietest life is more insightful than the most visible.

Who is the subject of the personal account?The subject is the person about whom the account is composed. The personal accounts of famous individuals often seem familiar—celebrities or politicians defending their reputations or confessing secrets. They tell the story of a life lived publicly.

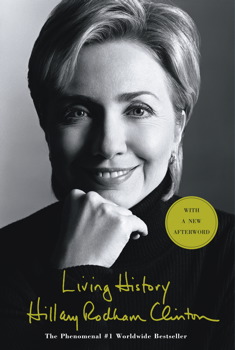

But what about accounts of people who are less well known? The first thing to ask when reading this sort of account is, “Who is this person?” How do they fit into a larger historical context? How do they identify themselves in relation to citizenship, age, gender, ethnicity, and education level? Think about the time and place in which the individual exists, his or her socioeconomic context. What living conditions might affect the individual’s worldview? Next consider the individual’s particular role in his or her community. Does the individual speak from a position of power or authority? Why or why not? What is the accepted view of this individual’s place in society? Does the account suggest dissatisfaction with a perceived role? Or conflict in a personal situation? Or a celebration of the status quo? Why is this person offering an account of his or her life? Hillary Rodham Clinton and Althea Gibson would explain their lives in different ways. While Clinton might take care to protect and defend her own influence and her husband’s political record, Gibson might be freer to talk about influences that shaped her rise to success in a world of sports long tainted by racism.

How does the form of the personal account influence content?The form of a personal account influences its meaning and our understanding. Was this record of a person’s life experience written formally and for public consumption? Or does it come from a secret cache of private musings that the subject never intended for public display? Is the account handwritten or typed? Will this affect its length or breadth of detail? Was the account part of a larger work with broader perspectives, or is it a consideration of a particular moment in time? How will women’s narrations differ from those of men? How do their views and roles in life affect their sense of freedom to write? Do men have a greater sense of obligation to record their life stories for posterity? Do they have greater access to education, writing materials, and publishing sources? Will the answers to these gender-related questions differ depending on the historical period? Socioeconomic status? If the account was written directly by the subject, what was the format? What was the influence of the format on content? For many, literacy will determine the form of the account. For example, a personal account by a slave during the early American colonial period would have been written painstakingly, perhaps with a quill pen, on paper that was expensive and not readily available. In addition, there would have been precious little leisure time in which to write—assuming that the individual had experienced the luxury of having learned to write in the first place. What would such an individual write about? The issues that drove such a personal account would likely have been serious and pressing matters relating to social history or the impact of politics on personal welfare.

By contrast, the e-accounts of a 21st-century college student dealing with life away from home, also historically relevant, would reflect many years of education and self-reflection, a presumption of access to resources for the recording of personal accounts, and could more easily be limited to internal reflections rather than a struggle with political and social constraints. Thus the form of a personal account can tell us a great deal about the circumstances of the writer and his or her historical context. The account’s voice reflects a choice that suits a particular audience and indicates motivation on the part of the narrator. The author is always speaking to a particular audience. Sometimes that audience is the self because some accounts are never meant for other people’s eyes. When other audiences are in mind, it may be readily evident in the language itself. Colloquial language indicates a desire to connect with a common audience, while formal language demonstrates the need to lend credibility to an account for public consumption. In Islamic contexts, the personal account is a specific style called the tarjama, which dates to the 10th century. Although written by the subject, it uses the third person to evoke a sense of objectivity. Furthermore, the tarjama includes specific features and leaves out others. A person’s tarjama includes a genealogy, a description of formal education and Qur’anic memorization, the names of teachers, books and subjects studied, examples of the student’s poetry, and dates to verify and set in context the life story. The tarjama clearly is an account of all that matters: education in a spiritual context and place in the learned community. This kind of writing, taking account of one’s life, reflects an individual’s character and piety rather than consisting of an internal monologue. In addition to the limiting nature of the tarjama itself is the gender bias found in some Islamic contexts. In Iran, for example, it has been rare to find a personal account by a woman because the nature of gender roles requires a woman to remain veiled, both physically and metaphorically. The personal accounts that do exist from this culture are, by virtue of their public nature, reflective of women less respectable than those whose stories remain hidden in the privacy of the domestic domain. While this is not true in every Muslim community, it can serve as a warning that what is written and told publicly is not necessarily representative of the whole community.1 1 Dale F. Eickelman, “Traditional Islamic Learning and Ideas of the Person in the Twentieth Century” in Martin Kramer, ed., Middle Eastern Lives: The Practice of Biography and Self-Account (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1991), p. 39.

What is the motivation for the personal account?

|

||

Primary Sources

Sample Analysis

Sample Analysis: Fatima Mernissi's Childhood Memoir, Dreams of Trespass

Fatima Mernissi is a professor of sociology at Mohamed V University in Rabat, Morocco and an internationally recognized authority on feminism and Islam. This engaging account of her childhood includes descriptions of the secluded harem life she lived in the city as well as of the freer, happier time spent at her father’s country house where several of his wives lived. She depicts the calm garden and fountain in the heart of the city house, escape to the roof on hot nights, the view from the roof of the “outside,” forbidden to her in her adolescence, and a yearning to be free to go out into the world as her brothers could.

Fatima Mernissi is a professor of sociology at Mohamed V University in Rabat, Morocco and an internationally recognized authority on feminism and Islam. This engaging account of her childhood includes descriptions of the secluded harem life she lived in the city as well as of the freer, happier time spent at her father’s country house where several of his wives lived. She depicts the calm garden and fountain in the heart of the city house, escape to the roof on hot nights, the view from the roof of the “outside,” forbidden to her in her adolescence, and a yearning to be free to go out into the world as her brothers could.

At the country house, by contrast, she hears stories about the wild wife who rode in on a horse and was “tamed” by her father, the wife who used to climb and sit in trees reading a book, and the picnic during which women swam in the river as they washed pots. It all sounds lyrical and pleasant. The city life confirms the Western stereotype of Muslim women being kept in seclusion against their will while the country life allows them license to control their actions.

Students at a Moroccan university described the book as autobiography, but many Moroccans call the story fiction. Other Moroccans simply dismiss the concern, saying that Mernissi writes for the West. Indeed, Western critics consistently have welcomed her works, especially this one. They applaud her ability to describe clearly a little-known culture that has long held fascination for the West. The notion that the book is fiction is based on the testimony of individuals who knew Mernissi as she was growing up and her own response to challenges in which she attests that the book serves to provide an accurate image of an amalgam of women’s situations.

The reader is left wondering what is true, yet the question of truth may have many answers. As a sociologist, Mernissi favors the case study approach to analysis, which can offer valuable insights. On closer examination, it is evident that her autobiography is not narrative, but a series of stories told to her by women of varied ages, classes, and backgrounds. Mernissi has used such storytelling technique effectively in several other nonfiction works. As a respected professor, an internationally known scholar, and an accomplished author and critic of Islamic law and custom with regard to women’s rights, Mernissi knows that her “Scheherazade” approach to communication, being a compelling storyteller, is an effective way to control and educate an audience without overt demonstrations of power. Ignoring criticism, she stands by her portrayal of life as it was for Moroccan women, confident that the picture she paints is accurate and informative.

As a teacher, I welcome the opportunity to draw all these contradictions into a conversation on the issues of truth and perception, especially in relation to the telling of a personal account. Mernissi’s views of growing up female in a traditional Islamic culture offer insight into stereotypes that she, a Muslim woman intimately associated with Moroccan culture, can offer. While everything she describes may not have happened exactly as portrayed, it nevertheless is representative of a Moroccan woman’s experience growing up in the 20th century. Mernissi paints a picture of life that is useful in offering insight into another culture, and more specifically, a woman’s particular place in that setting.

Furthermore, to some extent her portrayal of this as her life is indeed accurate in her own mind. After all, memory is selective: people’s responses to experiences vary and people’s memories of experiences change with time and influence. Events happen in a person’s life between lived experiences and recording those events can shape their telling. Mernissi’s account is valuable because it reflects her own internalization of the Moroccan Muslim culture in which she grew up.

It would be useful to compare Mernissi’s account with that of someone like a Daisy Dwyer’s 1978 study Images and Self-Images: Male and Female in Morocco or Susan Davis’s Patience and Power: Women’s Lives in a Moroccan Village (1983). Davis’s Western, anthropologically-oriented views offer good counterpoints. Mernissi’s description of growing up in urban and rural Muslim homes, with varying degrees of freedom, is true to the anthropological accounts of the region. Whether her personal account is literally accurate for her own personal experience or merely representative, it is nevertheless a valuable portrayal of one kind of life in a particular place and time.

Sample Analysis: Marjorie Shostak's Account of Nisa, a !Kung Woman

Nisa’s story begins with author Marjorie Shostak’s introduction addressing the context for her conversations with Nisa, a woman of the !Kung ethnic group in southeast Africa. Shostak’s acquaintance with Nisa was not immediate, but evolved over a long period of field-work residence in the area. Shostak also had extensive contact with many other women whose testimonies confirmed the veracity of Nisa’s. Ultimately, Shostak decided that Nisa was the right informant on women’s roles among the !Kung because Nisa “understood the requirements of the interviews, she summarized her life in loosely chronological order; then, following [Shostak’s] lead, she discussed each major phase in depth.”4

Nisa’s story begins with author Marjorie Shostak’s introduction addressing the context for her conversations with Nisa, a woman of the !Kung ethnic group in southeast Africa. Shostak’s acquaintance with Nisa was not immediate, but evolved over a long period of field-work residence in the area. Shostak also had extensive contact with many other women whose testimonies confirmed the veracity of Nisa’s. Ultimately, Shostak decided that Nisa was the right informant on women’s roles among the !Kung because Nisa “understood the requirements of the interviews, she summarized her life in loosely chronological order; then, following [Shostak’s] lead, she discussed each major phase in depth.”4

The relationship that developed between Nisa and Shostak was that of teacher and student. And although Nisa and her family were fed and housed by Shostak during the period of their work together, it was understood that Nisa’s task was to teach Shostak about !Kung womanhood, educating her in a dispassionate way, as a caring, but objective instructor. Shostak conducted fifteen long interviews over a two-week period, and six more four years later. Nisa’s stories constitute only eight percent of all the interviews Shostak conducted with !Kung women, so she amassed a great deal of comparative data. Shostak rearranged the stories into chronological order for her book, but she tried to remain true to the nuances of !Kung forms of expression throughout the material.

One of the most important issues Shostak discusses in the introduction is her need to become capable in the !Kung language so that she could speak directly to the women among whom she did research. All cultures have different modes of communication within cultural subgroups that depend on slang, symbolic language, and nonverbal modes of communication. Even with the help of language tutors and hearing the language spoken all around her everyday, Shostak was unable to communicate in even a rudimentary way until she had been there six months, and the first real communication she had with !Kung women was in her tenth month of field work. This is the first level of “common language” necessary to the communication of personal accounts.

For Shostak and many other field workers, an important level of common language had to do with gender. Women are freer to talk with other women of foreign cultures than to mix with men. This also accounts for the relative dearth of material on women’s lives until very recently in the history of scholarship: most scholars in the field have, until the 20th century, been men who had little access to or focus on women’s lives. Interestingly, Shostak’s conversations with Nisa make for compelling reading because they are so ordinary: any young woman will be able to relate to Nisa’s own life, despite the cultural and geographic distance between them.

Section titles indicate a chronology from birth and first impressions through the discovery of sexuality, marriage, childbirth, maturity and old age. In addition, Nisa considers the universal questions of gender relations, health and healing, and dealing with loss in old age. Shostak considers that Nisa’s early memories may be more exaggerated than those of her more mature years, and cautions against a reader’s making Nisa’s story representative. It is but one of many such life histories that, because of their personal nature, will be different for each individual.

As young women reading Nisa’s life learn, there is as much about Nisa for them to compare as to contrast with their own experiences of being young and female in the world. Ultimately, no amount of common spoken language or shared gender identity will allow a field worker to know another’s perspective completely, but the investment of time devoted to language learning and familiarity with the subject’s place in society will lead to the acquisition of a deeper understanding.

4 Marjorie Shostak, Nisa: The Life and Words of a !Kung Woman (New York: First Vintage Books, 1983), p. 39.

Bibliography

Baisnee, Valerie. Gendered Resistance: The Autobiographies of Simone de Beauvoir, Maya Angelou, Janet Frame, and Marguerite Duras. Atlanta, GA: Rodopi, 1997.

The author investigates the autobiographical works of four prolific women writers to examine the ways in which they choose to portray their own lives in their writings.

Beauvoir, Simone de. Memoirs of a dutiful daughter; translated by James Kirkup. Cleveland: World Pub. Co., 1959.

Bjorkland, Diane. Interpreting the Self: Two Hundred Years of American Autobiography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

This study sets out four models of self-understanding as they are revealed in American autobiography. Bjorkland analyzes these models as “dialogues with history,” and sources for data in the social and behavioral sciences.

Caplan, Pat. African Voices, African Lives: Personal Accounts from a Swahili Village. London: Routledge, 1997.

This is an ethnography of a Swahili family in Tanzania with whom the author has been friends for thirty years. It explores the changes in their lives over that period of time.

Clinton, Hillary Rodham. Living History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003.

Crapanzano, Vincent. Tuhami: Portrait of a Moroccan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

This ethnography of a Moroccan man focuses on his psycho-social perceptions in response to his society.

Davis, Susan. Patience and Power: Women’s Lives in a Moroccan Village. Cambridge: Schenkman, 1983.

Denizin, Norman K. Interpretive Biography. London: Sage Publications, 1989.

Denizen discusses how biographical texts are written and read, focusing on the gathering and interpretation of lives and the discovery of epiphanic moments in a life.

Dwyer, Daisy. Images and Self-Images: Male and Female in Morocco. New York: Columbia University Press, 1978.

Eickelman, Dale F. “Traditional Islamic Learning and Ideas of the Person in the Twentieth Century” in Kramer, Martin, ed., Middle Eastern Lives: The Practice of Biography and Self-Account,35-39. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1991.

Eickelman explores examples of self-images of Muslim men of learning to distinguish between the individual and the person (the individual is the mortal human being, while the person reflects cultural influence). He discusses the concept of tarjama, an autobiography that includes genealogy and qualifications of the writer and is written in the third person to indicate credibility.

Frank, Anne. The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition, edited by Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler; translated by Susan Massotty. New York: Doubleday, 1995.

Goodson, Ivor F. and Pat Sikes. Life History Research in Educational Settings: Learning from Lives. Philadelphia: Open University Press, 2001.

This study considers the process of developing life stories and techniques, epistemology, social context, ethics, and dilemmas in the process of producing life stories. In the chapter on epistemology, consideration of life history from the perspectives of the life storyteller and the life historian are of particular interest.

Gibson, Althea. I Always Wanted to Be Somebody. New York: Harper, 1958.

Griaule, Marcel. Conversations with Ogotemmeli: An Introduction to Dogon Religious Ideas. London: Oxford University Press, 1965.

This classic anthropological study began with the search for a personal account and resulted in the full-blown philosophy of the West African Dogon people, narrated by a Dogon elder, Ogotemmeli. Ogotemmeli felt the people’s philosophy of life was more important for a foreigner to hear than his own, small life story.

Kadar, Marlene, ed. Essays on Life Writing: From Genre to Critical Practice (Buffalo, NY: University of Toronto Press, 1992).

This collection of essays deals with the wide range of genres that constitute life writings: autobiography, journals, memoirs, letters, testimonials (including court testimony), oral accounts, fiction and poetics. Many of these are unintentional testimonies that are interpreted by scholars as personal accounts.

Kenyon, Gary M. and William L. Randall. Restorying Our Lives: Personal Growth Through Autobiographical Reflection. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1997.

This study is premised on the idea that every individual not only has a story to tell, but is a living story. Using story as the metaphor for life, the authors discuss the process of telling and retelling about our lives. They note that stories change in the act of preserving them in written form and that stories vary depending on what historical moment in that person’s life is reflected in the story. More importantly, they emphasize the fact that at any given moment each individual contains many stories; the one you are hearing is but one portion of that person’s experience.

Kramer, Martin, ed. Middle Eastern Lives: The Practice of Biography and Self-Account. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1991.

This volume includes eight studies by scholars of the Muslim and Jewish Middle East. They discuss the idea of self-awareness and its documentation in these cultural contexts, the enduring legacy of personal account in this world region (dating back to Assyria and early Persia), and the relationship of personal account to political history.

Lejeune, Phillippe. “Teaching People to Write Their Life Story,” in On Autobiography, 216-31. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Lejeune explores the question of why and how one goes about selecting aspects of a life to recount.

Lewis, Bernard. “First-Person Account in the Middle East” Middle Eastern Lives: The Practice of Biography and Self-Account, edited by Martin Kramer, 20-34. New York: Syracuse University Press, 1991.

Bernard Lewis notes that the genre of first-person account in the Middle East dates back at least as far as 1991 BCE (Amenemhat of Egypt) and 1275 BCE (Hittite king Hatusilis) who recorded their accomplishments for posterity. Lewis discusses the impetus for autobiographies by men of learning, royalty, and religious figures. They sought to record their lives in the categories of “what I did,” “what I saw,” and “what I thought.”

Mernissi, Fatima. Dreams of Trespass: Tales of a Harem Childhood. Reading: Addison Wesley, 1994.

Milani, Farzaneh. “Veiled Voices: Women’s Autobiographies in Iran” in Women’s Autobiographies in Contemporary Iran, edited by Afsaneh Najmabadi, 1-16. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard Middle Eastern Mongraphs XXV, 1990.

Milani explains the irony of Muslim women’s autobiographies, which require revealing what is concealed. The ideal in Islam involves concealing what is revered (the body, the privacy of the home), so to write a personal account is to diminish by expression what should remain private: thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

Munson, Jr., Henry, Rec., Trans., ed. The House of Si Abd Allah: The Oral History of a Moroccan Family. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984.

Munson has recorded interviews with members of this Moroccan family who recount their perceptions of 20th-century history and talk about family members from the late 19th century to the present. His discussion of methodology in recording oral history is especially useful.

Najmabadi, Afsaneh, ed. Women’s Autobiographies in Contemporary Iran. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard Middle Eastern Mongraphs XXV, 1990.

This Harvard monograph consists of four studies of Muslim women’s autobiographies, with a focus on Iranian culture and the limitations there for women’s free expression of the self.

Ostle, Robin, Ed de Moor and Stefan Wild, eds. Writing the Self: Autobiographical Writing in Modern Arabic Literature. London: Saqi Books, 1998.

The 24 essays in this collection address the genre of autobiography in the context of Arab culture. Three of the essays deal specifically with women’s works.

Oufkir, Malika. Stolen Lives: Twenty Years in a Desert Jail. New York: Hyperion, 1999.

Romero, Patricia, ed. Life Histories of African Women. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Ashfield Press, 1991.

This collection of seven brief life histories of African women spans the continent and several centuries of history. Some of these essays are based on interviews focused on women’s life stories while others are life histories reconstructed from archival materials.

Shostak, Marjorie. Nisa: The Life and Words of a !Kung Woman. New York: First Vintage Books, 1983.

Smith, Mary. Baba of Karo, a Woman of the Moslem Hausa. New York: Praeger, 1964.

While Smith’s husband was interviewing traditional Hausa men in northern Nigeria in the late 1950s, she sat down to talk with an old Hausa woman named Baba who had lived through the British colonial occupation of Nigeria. This is the account of Baba’s experience living in rural Nigeria and seeing her traditional way of life affected by the arrival of the British. Her responses to Mary Smith’s questions frame the discussion, which is focused on domestic and political issues in a particular time and place.

Soyinka, Wole. The Man Died: Prison Notes of Wole Soyinka. New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Thomson, Alistair. “Life Histories, Adult Learning and Identity” and Mary Lea West, and Linden, “Life Histories, Adult Learning and Identity” in The Uses of Autobiography, edited by Julia Swindells, 163-76, 177-86. Bristol, PA.: Taylor and Francis, 1995.

This two-part essay investigates perceptions about education from the points of view expressed in life histories, with a focus on adult learning, motivation, and decision-making in the pursuit of education.

Vansina, Jan. Oral Tradition: A Study in Historical Methodology. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Company, 1965.

This classic text on field methodology in African history is wholly applicable to the assessment of personal accounts anywhere in the world. It addresses the varieties of testimonies a researcher encounters, such as: intentional, unintentional, hearsay, symbolic, stereotypical, idealized, fixed, and free. Vansina discusses the distortions that commonly occur as human beings struggle with the confluence of memory and historical context, endeavoring to reconstruct their lives and make sense of their times.

Credits

Beverly Mack is a Professor Emeritus of African Studies in the Department of African and African American Studies at the University of Kansas. She holds a PhD in African Languages and Literature from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and her training includes specialization in oral traditions in history and literature in Africa. She has done fieldwork in Nigeria and Morocco, and has also worked in Sierra-Leone, the Ivory Coast, and Guinea-Conakry. Much of her research focuses on the relationship between women and power in Africa, and her book, Muslim Women Sing: Hausa Women’s Scholarship and Song in Contemporary Northern Nigeria, was published in 2004.

For example, readers of the autobiography by Hillary Rodham Clinton, Living History, probably do not need many clues about its historical context or Clinton’s role in American political life. Readers of the late Althea Gibson’s autobiography, I Always Wanted to Be Somebody, might not know that she was the first African American woman tennis champion. Clinton is well known in contemporary times to a broad range of people, regardless of their political or professional interests. Gibson, however, would be a familiar figure only to a more select group of individuals whose interests include sports history and civil rights issues in American history.

For example, readers of the autobiography by Hillary Rodham Clinton, Living History, probably do not need many clues about its historical context or Clinton’s role in American political life. Readers of the late Althea Gibson’s autobiography, I Always Wanted to Be Somebody, might not know that she was the first African American woman tennis champion. Clinton is well known in contemporary times to a broad range of people, regardless of their political or professional interests. Gibson, however, would be a familiar figure only to a more select group of individuals whose interests include sports history and civil rights issues in American history.