Browse Primary Sources

Locate primary sources, including images, objects, media, and texts. Annotations by scholars contextualize sources.

Misión San Francisco de la Espada

The Misión San Francisco de la Espada is one of the many churches that Spanish friars founded along the modern-day Southwestern United States. This area was a frontier-zone, bordering indigneous communities and British and French territories. It was established in the mid-eighteenth century near San Antonio, Texas to evangelize the native peoples.

Misión San José y San Miguel de Aguayo

The San Jose Mission in San Antonio, Texas is one of the most complete complexes in the southwest. It was built in the mid-eighteenth century to evangelize approximately 300 indigenous people.Their tiny, two-room living quarters lined the interior walls of the complex. These individuals lived and worked there under the supervision of the church authorities.

Misión Santa Cruz de San Sabá

The ruins of the Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá are located in Menard, Texas. It once operated as a Spanish colonial church and military outpost. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Spanish friars established many such structures across the Southwestern United States. Each of these sites aimed to evangelize the local communities.

Nuestra Señora de la Bahía del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga

This church was built as part of the larger project of indigneous evangelization, in which the Spanish Crown sent missionaries along the northern border of its North American possessions to establish churches and convert the natives.

La Misión de Corpus Christi de San Antonio de la Ysleta del Sur

Although the Spanish Crown claimed possession of the modern-day US borderlands, it was not able to send many settlers to the region. As a result, the priests and missionaries stationed there often took on both religious and government responsibilities. They became the spiritual, political, and economic overseers of the local indigenous populations.

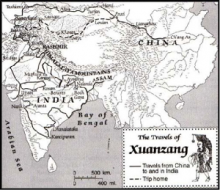

Map of the Travels of Xuanzang (629 AD - 645 AD) Journey to the West

This Schematic Map shows the entire "Journey to the West" as made by the Chinese Monk Xuanzang (Hsüan-tsang) on the Silk Road between China and India in the years 629 AD to 645 AD. The Path of the Journey to led from the Chinese Capital in Shaanxi Province of China acros the Yellow River to the westernmost pass of the Great Wall of China.

Buddhist Records Of The Western World

Xuanzang ( or Hiuen Tsiang) was a Chinese monk ( 602-664) who went to India to study Buddhism. After he went back to China, he told his 17-year journey to his disciple, Bianji, who edited and wrote it in Chinese and published it with a title: da tang xi yu ji (the meaning of the title is the records regarding the western area of the Great Tang dynasty).

Edifying and curious letters of some Missioners of the Society of Jesus from foreign missions

After reaching and residing in foreign places, Christian missionaries sent different kinds of writings (letters, reports, notes, etc.) back to Europe. These writings, based on different Church orders to which missionaries belonged, are normally stored in different archives (most in Rome).

"The Money Market" Article

The London Evening Standard reported in 1881 that one transaction from the Sursuq (Sursock) and Debbas families caused the French stock market to decline. The Levantine companies had accumulated significant capital from silk and futures trading throughout the mid-nineteenth century.

Section of "The Bubbles of Finance"

Malcolm Ronald Laing Meason was a famous journalist and book author. As a respected authority on trade and finance, he possessed insider knowledge that journalists of articles like “Islam on the Ebb” did not. In 1865 he witnessed the Levantine companies becoming wealthy from trading in futures.

Islam on the Ebb

This article is one of many newspaper articles coming out of Britain in the late nineteenth century. It reports that families in Beirut were becoming wealthy. They were “even beating the West on its own commercial ground.” These journalists find that the reason for Middle Eastern success is their ability to adopt a “Western spirit.” Historians have repeated this Eurocentric view as fact.

Negro Slavery Described by a Negro

Ashton Warner lived in the British Caribbean colony of Saint Vincent in the early 1800s. He was raised free before being re-enslaved at the age of ten. In this passage, he describes his experience laboring on a sugar plantation. Although Warner was not forced to labor in the cane fields, he describes his horror at the prospect that he might need to complete that work.

The World: Map of N. & S. America

Matthaeus Seutter was an acclaimed German mapmaker in the early eighteenth century. He published maps that introduced the geography of the Americas to many people who would never set foot on the continents themselves. The drawings on the upper left and lower left of this map represent many of the things that Seutter—and other Europeans—prized in the New World.

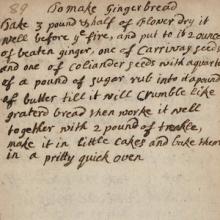

Ginger bread recipe

This late-seventeenth century recipe for gingerbread shows how colonization in the Atlantic world changed what men and women in England would have eaten. The recipe includes ginger and sugar. While both of these commodities were known by Europeans prior to Columbus’s journeys to the New World, they were often grown on Caribbean plantations for export to Europe.

Teatro Nacional Cervantes

The Cervantes Theater is located in Buenos Aires, Argentina, near the historically aristocratic zone of Recoleta. Actress María Guerrero and her husband Fernando Díaz de Mendoza played a major role in the establishment of this theater, which was officially inaugurated on September 5, 1921.

Uruguayan Jail Cell Door

The nation of Uruguay was ruled by a military dictatorship from 1973 to 1986. During this period, harsh military regimes dominated many South and Central American countries. For more than a decade in Uruguay, government and military officials committed countless acts of kidnapping, imprisonment, and execution.

Maguire Residence

This mansion is one of the last remaining palace-like residences in Buenos Aires. It was built in the 1890s on a street with many other similar homes, Avenida Alvear. Many of these extravagant houses have been demolished or converted into hotels.

Coin minted by Constantine

Constantine erected large monuments to his rule, most notably the Arch of Constantine in Rome, but he also portrayed his religious sentiments and celebrated his reign in smaller ways, through coins and portraits. This is a copper alloy coin, minted in Constantinople in 327, the type of coin that ordinary people would have used for business transactions.

Selections from Eusebius, Life of Constantine

The most important record that remains of Constantine’s life is a biography written shortly after his death by the historian and Christian bishop Eusebius of Caesarea (ca. 263–339 ?), a close adviser to Constantine.

Constantinian Edicts

Many of the records that survive from Constantine’s reign are official edicts and proclamations, written on papyrus and parchment. This is a series of edicts issued by Constantine regarding religion, beginning with the original edict of toleration from 311 signed by three of the then four rulers of the Roman Empire: Lactantius, Licinius, and Constantine.