Short Teaching Unit: The Omani Empire and the Center of the Emerging Global Economy, 1500-1850

Overview

This essay pushes back against European-dominated narratives of world history to suggest that the Omani Empire was a crucial space for the emergence of our present-day system of global capitalism. By 1850, the Omani Empire was a marketspace with its capital in Zanzibar, stretching from there north to the Persian Gulf. Most broadly, understanding the Omani Empire’s crucial role in helping forge our present-day global economic system is important for seeing the continued historical relevance of the Indian Ocean world.

Essay

The history of Oman is entwined with the sea. Located on the southern edge of the Arabian Peninsula, Oman is surrounded by the Persian Gulf, the Sea of Oman, the Arabian Sea, and the Indian Ocean. Muscat, its capital today, is nestled in a bay, its shore protected on three sides by mountains. In antiquity the Greek geographer Ptolemy described Muscat’s privileged location, referring to it as the “hidden harbor” of the Indian Ocean. More modern writers also highlighted its privileged and unique geography. “The location of this place is far different from any that I have yet seen,” wrote an American sailor in 1847, “were it not or an island that serves as a landmark outside of the harbor, it would be difficult to find.”

The American sailor’s ostensible difficulty finding Muscat belies its historical significance as part of a deeply connected commercial, social, and political Indian Ocean world, a world connecting Africa to China and all points in between. Muscat and other similar port cities along Oman’s coast were vital ports in this ancient and perpetually circling maritime trading world. For the last four thousand years, Omani traders and seafarers have traversed these networks stretching from the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa to the Indian subcontinent, Indonesia, and China. The American sailor’s remark about Muscat’s geography is important for another reason, too. Europeans and especially Americans were relative latecomers to this world.

Older styles of world history tended to use European empire as a starting point for interpreting all other parts of the world, especially in the modern era. One scholar who challenged this was the world historian Marshall Hodgson, who showed how Muslim societies in the Indian Ocean actually contained European powers, “reducing them to one element among others in the multinational trading world” of the Indian Ocean. The Omani Empire, by 1856 stretching from southern East Africa north to Gwadar in the Persian Gulf, is an important space for seeing how this history played out.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to establish a presence in the Persian Gulf. In 1505, they sailed into Muscat harbor, bombarding and invading Muscat and other Omani cities. Amidst brutal fighting – most of it at sea – the Omanis relegated the Portuguese to rather small pockets in and around Muscat. By 1650 the Omanis, under the rising Yarubi Dynasty, forced their complete evacuation from the region. Nasir bin Murshid al-Yarubi, the first leader of the Yarubi Dynasty, came to power in 1624, beginning a long-term process of remaking Omani and broader Indian Ocean social, political, and economic practices to suit their entwined imperial interests. These interests were primarily rooted in commercial aggrandizement and the official protection of their own merchants. They built one of the most powerful navies in the Indian Ocean, and began using this navy as an instrument of their state policy. But their expansion wasn’t always rooted in violence and coercion. When the Yarubi defeated the Portuguese in Muscat, they demanded that the Portuguese, before withdrawing, restore to religious and ethnic minorities in Oman’s port cities their property and possessions, which the Portuguese had plundered. The Omanis also stipulated that the Portuguese could remain in the region as merchants, if they agreed to pay tribute to the Yarubi.

That the Omanis demanded the restoration of property and rights to minorities in their domains reflects an important component of why their burgeoning empire would come to flourish to such great extents: though they carved out market spaces with great acts of violence, they sustained the flourishing of these markets by fostering a unique form of cosmopolitanism aimed at attracting as many different people as possible for augmenting market competition. By 1650, the Yarubi had lifted the mandate that non-Muslims pay the jizya, the traditional tax technically required for non-Muslims to pay while living in a Muslim polity. They also established other rights of religious liberty, such as allowing Hindus to build temples, keep sacred cows, and practice other rituals important to their faith. The Hindu merchant community thus became increasingly important to the Omani Empire, by the nineteenth century essentially acting as their state treasury.

These domestic policies were combined with an aggressive foreign policy aimed especially at mitigating the influence of the Portuguese and other Europeans, whose own commercial practices were aimed more at establishing strict mercantilist monopolies rather than a more cosmopolitan, competitive marketspace. The Omanis were master seamen, and experienced in naval combat. In fact, amongst the Omanis, the Portuguese were nicknamed the “hen-hearted fellows.” By 1660, one French naval officer concluded that the Omanis were “the masters of all the navigation and commerce.”

The Omanis’ ascension over the seas took them to East Africa, a thriving region long a center of world trade. One of the primary reasons the Omanis began to seek more power in East Africa was to consolidate their hold over the slave trade. In fact, slavery was woven throughout every aspect of the Omani Empire. The Omanis expanded not only the trade in humans, but also slave-based plantation agriculture. In 1698, the Omanis laid siege to Mombasa, a critically important port city in present-day Kenya. The Portuguese would remain in small pockets, and the French and British were increasing their presence in the Indian Ocean, but by 1700 the Omanis had carved out control over a coherent market space stretching along East Africa’s coast north to the Persian Gulf. This burgeoning empire was not ruled in a clearly delineated, vertical political structure, but was rather held together by a loose web of governors, judges, merchants, and other bureaucrats who all paid some form of tribute to the Yarubis while maintaining most of their control over local matters.

Around 1750 a new ruler came to power, Ahmad bin Said Al Busaid, the first leader of what became known as the Busaidi Dynasty. This family remains in power in Oman today. As with his Yarubi predecessors, maritime trade was foremost in Ahmad’s strategic thinking. When he was elected leader, he at once began reorganizing the military, establishing more government institutions, and developing his maritime fleet. He established different agents in charge of functions like customs, shipping regulations, and even local security. Ahmad died in 1778, but his successors continued a similar path. One of his successors, Hamad, moved the capital to Muscat, where it remains today, and introduced a flat 6.5% customs fee for all traders, regardless or religion or nationality. In 1786, he established formal diplomatic relations with Tipu Sultan, ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in India. He also carved out direct trade routes between Oman and the Kalat state of Balochistan (present-day Afghanistan), an important step in projecting Omani power across the Gulf into Central Asia.

Beginning in 1800 the still-growing Omani Empire began a new phase of its history when its leader, Sultan bin Ahmad, signed a formal commercial treaty with Great Britain. Signing this treaty could be interpreted as a sign of emerging British mastery over the seas. Interpeting it against a broader and longer historical arc, however, also allows us to see how it can be interpreted as one instance of how the relatively new world of the North Atlantic became incorporated into the far longer-standing Indian Ocean world.

In 1804, Sultan bin Ahmad died. He was succeeded by his son, Said bin Sultan, who ruled until 1856. By that year, the Omani Empire was a relatively clearly delineated oceanic marketplace stretching from Zanzibar in southern East Africa north to Gwadar, in present-day Pakistan. Immediately upon assuming power (in either 1804 or 1806), Said’s first goal was establishing maritime dominance in the Persian Gulf. His greatest competition in the area were the Qawasim, a group mostly from present-day United Arab Emirates. He launched brutal naval campaigns against them, and signed into a formal naval alliance with Great Britain. After establishing security in the Gulf, in 1840 he moved the capital of his empire to Zanzibar.

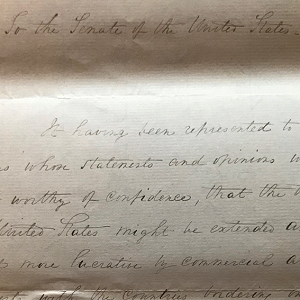

Under Said, Zanzibar became a monied metropolis, bursting with diplomats, traders, and entrepreneurs from around the world. Its importance for the world economy is reflected by a letter U.S. President Andrew Jackson wrote in 1834 to the Senate, in which he described how, to strengthen the faltering American economy, he had sent a secret envoy to negotiate a commercial treaty with Said bin Sultan in Muscat. Other states did the same, and by the time Said died in 1856 Zanzibar was home to three foreign consulates – Great Britain, France, and the United States – a rather astonishing fact when one considers just how small the island actually is.

Shortly after Said died, the empire was divided into two sections: one based in Muscat, and the other based in Zanzibar. From the early 1600s until the mid-nineteenth century, however, the Omani Empire had been a formative space in the emergence of the first truly global economy. The domains of this empire were a space in which local African, Arab, Indian, and other Indian Ocean peoples incorporated the newly emerged North Atlantic world into their commercial orbit, finally linking the Atlantic into the Indian Ocean world. The Omani Empire was a pivotal space for the global conjunctures that intensified market connections between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. In this way, for studying and teaching world history the Omani Empire presents an important, yet mostly overlooked space for understanding important themes of world history, not the least of which is understanding how, for most of human history, Europe has been a periphery, not a core.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Bishara, Fahad. A Sea of Debt: Law and Economic Life in the Western Indian Ocean, 1780-1950. Asian Connections. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Hodgson, Marshall G.S. Rethinking World History: Essays on Europe, Islam, and World History. Edited by Edmund Burke, III. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Ibn Ruzayq, Ḥamīd ibn Muḥammad. History of the Imāms and Seyyids of ʿOmān: From A.D. 661-1856. Translated by George Percy Badger. Cambridge Library Collection. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Roberts, Nicholas Paul. “A Sea of Wealth: Sayyid Saʿid bin Sultan, His Omani Empire, and the Making of an Oceanic Marketplace.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Notre Dame, 2021.

Saʿīd b. Sirhān, Sirhān b. Kashf Al-Ghumma [Annals of Oman]. Translated by E.C. Ross. Calcutta: G.H. Rouse, Baptist Mission Press, 1874.

Sheriff, Abdul. Slaves, Spices, and Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770-1873. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1987.

Credits

Nicholas Roberts is Assistant Professor of History at Norwich University. In academic year 2022-2023, he will be the Inaugural W. Nathaniel Howell Postdoctoral Fellow in Arabian Peninsula and Gulf Studies in the Corcoran Department of History at University of Virginia. While there, he will complete a book manuscript based on his dissertation, which won the John Highbarger Memorial Dissertation Prize from the University of Notre Dame, the Gwenn Okruhlik Dissertation Award from the Association for Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, and Dissertation Award Honorable Mention from the World History Association. He earned his Ph.D. in History from the University of Notre Dame, where he was a Presidential Fellow.