Browse Primary Sources

Locate primary sources, including images, objects, media, and texts. Annotations by scholars contextualize sources.

Rights of Man

Thomas Paine (1737–1809) played a vital role in mobilizing American support for their own independence, and he leapt to support the French revolutionaries when Edmund Burke attacked. Elected deputy to the French National Convention in 1793, Paine nearly lost his head as an associate of the Girondins during the Terror. In his reply to Burke, Paine defended the idea of reform based on reason.

A Poem by Victor Hugo (1830)

In his poem “To the Column,” the great French poet Victor Hugo celebrates the memory of Napoleon.

This source is a part of the The Napoleonic Experience teaching module.

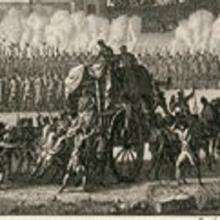

Arrival of the Royal Family in Paris on 6 October 1789

When the revolutionaries, led by thousands of women, marched to Versailles, they triumphantly seized and then brought the king to Paris, where he would live in the midst of his people. Here this image attempts to maintain a perception of royal pomp and grandeur, ignoring the reality that the king was forced against his will.

The King Returns to Paris

From Berthault’s series of great moments in the Revolution, this engraving presents a version of events on 6 October 1789 favorable to the King. Reminiscent of orderly ceremonial royal appearances, this image suggests that the outcome stemmed from the King’s own will and that his heroic intervention prevented the massed National Guard units from firing.

The Tennis Court Oath at Versailles by Jacques–Louis David

This amazingly rich sketch by Jacques–Louis David is one of the most famous works from the French revolutionary era. The thrust of the bodies together and toward the center stand for unity. The spectators, including children at the top right, all join the spectators. Even the clergy, so villified later, join in the scene.

Thomas Jefferson on the French Revolution

Although deeply sympathetic to the French in general and the revolutionary cause in particular, Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826) deplored the excesses of violence that took place even before the implementation of the Reign of Terror.

Alexander Hamilton on the French Revolution

Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804) represented the Federalist Party perspective on events in France. He, and they, supported the moderate phase of the Revolution, which they understood to be about U.S.–style liberty, but detested the attacks on security and property that took place during the Terror. In particular, Hamilton distrusted the popular masses.

Kant, The Contest of Faculties

The most influential German philosopher of the eighteenth century, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), set the foundations for much of modern philosophy. He lectured on a wide variety of topics, from astronomy to economics. In this short statement from 1798, he captures much of the significance of the French Revolution for his time.

Historical, Political, and Moral Essay on Revolutions, Ancient and Modern

The French novelist and essayist François–René Chateaubriand (1768–1848) was a royalist who for a time admired Napoleon. Like Burke, he denounced the revolutionary reliance on reason and advocated a return to Christian principles. Although Chateaubriand detested the revolutionaries and their principles, he recognized that the French Revolution required extended commentary.

The Philosophy of History

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) was a famous philosophy professor in Berlin whose lectures attracted many students, even though the lectures were extraordinarily abstract. The Philosophy of History was a compilation of his lectures given in 1830–31 and published after his death.

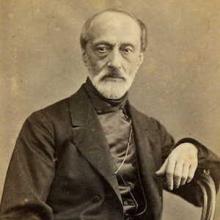

Mazzini on Revolutionary Nationalism

The journalist and politician Guiseppi Mazzini (1805–72) was the apostle of nationalism during the first half of the nineteenth century. He was exiled by the Austrians from his native Italy in 1831 and spent the next two decades working unsuccessfully through Young Italy, a secret society dedicated to beginning a European–wide revolution on the Italian peninsula.

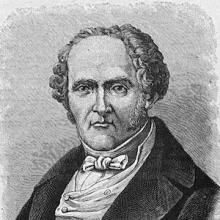

Charles Fourier on the Revolution

Charles Fourier (1772–1837) was a salesman for a cloth merchant in Lyons who conceived of a different form of social organization, called a "phalanx," that was part garden city and part agricultural commune. All jobs would rotate and a network of small decentralized communities would replace the state. He also believed that equal rights for women were necessary for social progress.

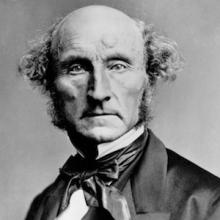

John Stuart Mill on the French Revolution

John Stuart Mill (1806–73), an English civil servant and philosopher, was a firm believer in the liberal, democratic, and anti–absolutist elements of the legacy of the Revolution and hoped to extend these concepts as widely as possible. Most famous for On Liberty (1859) and The Subjection of Women (1869), Mill was profoundly influenced by the French Revolution.

Alexis de Tocqueville on the French Revolution

The nobleman Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–59) was a historian, social critic, and politician who wrote a vastly influential work entitled The Old Régime and the French Revolution (1856). Tocqueville worried that although the revolutionary legacy was still alive and well, liberty was no longer its primary objective.

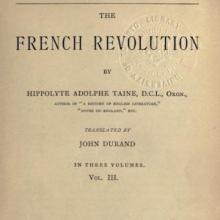

Hippolyte Taine on the French Revolution

Literary critic and historian, Hippolyte Taine (1828–1893) was lionized by late–nineteenth–century republican France. He emphasized rationalism and mathematical simplicity, being a bitter critic of the ideological abstractions that had occupied France since 1789.

De Maistre, Considerations on France

Joseph de Maistre (1753–1821) defended the absolutist legacy and the close alliance of throne and altar. He thought the Revolution and the republic it created in the name of reason and individual rights had failed. De Maistre and other staunch Catholic royalists believed that tradition and faith had to fill the void opened by the failure of the Revolution.

Le Bon, The Psychology of Revolution

Gustave Le Bon (1841–1931) disparaged the Revolution and the revolutionary legacy because he distrusted the common person, particularly when making collective decisions. His analysis of revolutionary crowds pictured them as primitive animals devoid of good decision–making abilities who had to be reigned in by a "strong man" or dictatorial figure.

Charles Maurras on the French Revolution

A classical scholar and militant atheist and anti–Semite, Charles Maurras (1868–1952) became involved in politics during the Dreyfus Affair (1893–1906) when he founded a group known as Action Française. He believed that as a result of the Revolution, France had become dominated by outside influences, namely, Protestants, Freemasons, and especially Jews.

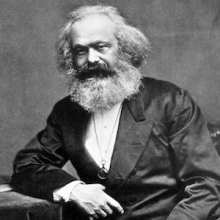

Karl Marx: The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

The German philosopher and founder of international communism, Karl Marx (1818–83), wrote on many occasions about the French Revolution, which he considered the first stage in an eventual worldwide proletarian revolution. In this relatively early work from 1852, Marx compares the French Revolution of 1789 with that of 1848.

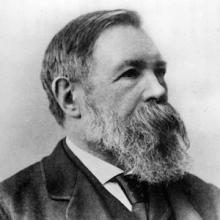

Frederick Engels: Socialism, Utopic and Scientific

Marx’s lifelong collaborator, Frederick Engels (1820–95), devoted himself to popularizing the ideas he had developed with Marx. In 1880 he published this pamphlet in French in order to explain the main principles of communism. In this excerpt Engels lays out the importance of the French Revolution in modern history and describes the reactions of the early socialists to its shortcomings.