Louis Arrives in Hell

Annotation

In classical mythology, the journey to Hell involved crossing the river Styx. Revolutionary cartoonists often invoked this image when describing the fate of their enemies. This is no exception. See the boat on the left with the dog, Cerberus, who was the guardian of the gates of the underworld. Arriving here is the headless Louis, greeted by other prior monarchs. In the right corner is a glade, showing a contrasting world in which people dance happily around the liberty pole.

Calonne, "Programs of Reform," Address to Assembly of Notables (1787)

Annotation

In 1783, Charles Alexandre de Calonne, a provincial noble, became royal finance minister. At first, he, like Vergennes, saw no need to rationalize the royal treasury or to appease the Parlements. However, by 1786 the deficit had become so huge—one–sixth of the total royal budget—that Calonne knew reforms (meaning more taxes or at least more loans) could no longer be put off. To obtain the support of regional nobles for such changes, the King called an Assembly of Notables. At the opening session, on 22 February 1787, Calonne addressed the assembly and proposed a uniform tax across the kingdom, to be administered by provincial assemblies of nobles and other elites. In other words, a royal minister was now suggesting that privileges from taxation should be replaced with a fiscal policy that would apply to all equally.

Protests of the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Committees of the Assembly of Notables (1787)

Annotation

To consider Calonne’s proposed reforms, the Assembly of Notables broke up into committees, each of which issued a report. In these reports, the Notables expressed general agreement with some reform proposals, including the idea of regional, representative assemblies. However, as we see below, various committees of the Assembly of Notables—composed almost entirely of provincial nobles and clergy—demanded that such assemblies take the form of provincial Estates. By this, they meant that representatives of each order would deliberate and vote separately—thus the assemblies would be dominated by the first and second estates. Furthermore, the Notables refused to consent to Calonne’s proposal of a general land tax that would be unlimited in amount and duration. Finally, they refused to accept any new taxation at all unless the minister demonstrated the need for it by opening royal treasury accounts to scrutiny.

Louis XVI’s Reply to the Parlement of Paris (1788)

Annotation

The fiscal and administrative reforms issued as royal decrees in the autumn of 1787 were opposed vociferously by the Parlements. To force their registration, the King held a "royal session" on 19 November 1787. Ordinarily at such a session, the magistrates of the Parlement of Paris would be allowed to vote on a royal decree. In this case, however, Louis broke with protocol by ordering the registration of his decrees without allowing the magistrates to vote. In this short speech given at Versailles the following spring, Louis XVI justified his move by restating the basic principle of absolutism—that royal decrees must be accepted as law when the King makes it clear that they are his will.

Royal Decree Convoking the Estates–General and the Parlementary Response (1788)

Annotation

By the fall of 1788, parlementary opposition to royal reforms had brought about a stalemate, with the Parlements refusing all reforms to the tax system. To gain the Parlement of Paris’s acceptance of new loans to keep the monarchy from going bankrupt, the new finance minister (Louis XVI’s fifth), Étienne–Charles Loménie de Brienne, decided to convoke an Estates–General for the first time since 1614. In his memoirs, he claims that he sought to keep conservative nobles from dominating the Estates–General and obstructing reforms by giving the Third Estate twice as many deputies as the other orders and by allowing all deputies’ votes to count equally. In this way, he hoped to build a working majority in favor of reform in the Estates–General. This decision was announced by a royal decree of 25 September 1788. The Parlement of Paris accepted this decree. However, it committed what became a major tactical error by demanding that the Estates–General follow the "forms of 1614," meaning that each order should have the same number of representatives rather than allow a "doubling of the Third" and that each estate should vote independently. When this resolution was published, it set off an outpouring of pamphlets and newspapers opposing the Parlements and calling for the Estates–General to vote "by head" rather than "by order."

"The King of the Third Estate" (June 1789)

Annotation

The King’s decision to accept the idea of a "National Assembly" and to order the deputies of all three orders to debate and vote as a single body met with sharp opposition within the royal entourage, especially among the aristocratic faction close to the Queen. In this passage, one of these hard–liners, the Countess d’Adhémar, expresses contempt for the idea of allowing any significant role for the Third Estate in the government. She seems here almost to pity the King for his unwillingness to preserve the traditional prerogatives of the crown and the higher–ranking nobility.

The King Speaks to the "National Assembly": Royal Session of 23 June 1789

Annotation

On 17 June, the deputies of the Third Estate, locked out of the Estates–General meeting hall in Versailles, convened in an empty tennis court, where they swore an oath. In it, they expressed their commitment to drafting a written constitution and proclaimed again that collectively, the deputies represented not three separate orders but a single French nation. In response, the King addressed the deputies in a "royal session" on 23 June; he rejected the claim of the Third Estate that it could constitute a "National Assembly" and reiterated that each deputy represented only the order that had elected him. As a compromise, however, Louis allowed that to consider matters concerning all three orders, especially the pressing issue of royal fiscal policy, all the deputies should debate in common, tacitly accepting some of the Third Estate’s arguments.

The Mayor of Paris on the Taking of the Bastille

Annotation

Jean Sylvain de Bailly, mayor of Paris and leader of the National Assembly, recorded his views of what was going on in Paris in the uprising of mid–July. Here we see the efforts of the delegates and their rejection by Louis XVI. As the men of the National Assembly could not imagine their country without a monarch, they refuse to blame the King. Yet they asserted themselves and the rights of the bourgeois militia.

View from the Top: the October Days

Annotation

In this letter to a friend, Madame Elizabeth, Louis XVI’s younger sister, takes an upbeat approach to the October march on Versailles. Even though the demonstrations clearly threatened the royal family, even forcing the Queen to flee her chambers, the outpouring of support obviously swayed the princess’s views. The actions of the crowd clearly indicated their split view that allowed a rage focussed against royalty to be combined with vocal approbation.

An Attempt at Conciliation: The Royal Address of 4 February 1790

Annotation

On 4 February 1790, the Marquis de Favras was executed for plotting to spirit the King out of France and stage a coup against the Constituent Assembly. The exposure of this plot generated such negative publicity for the crown that after the execution, the King addressed the Constituent Assembly and condemned Favras, declaring his support for the Revolution. At Necker’s prompting, he here "places himself at the head of the Revolution" and declares fidelity to the "nation" and to the constitution. In return, he requests that the National Assembly take up at last the question of the deficit. The speech is enthusiastically received in the assembly, and Pierre–Victor Malouet, a leading supporter of the crown, tries to exploit this support by asking the assembly to vote to confirm Louis as head of the army and state—ensuring a powerful executive role for the King in the new constitution. However, Malouet’s proposal is not adopted. Although an apparently well–thought–out and necessary attempt at conciliation, the speech is seen by hard–liners at court as a humiliating capitulation.

The King Seeks Foreign Assistance (20 November 1790)

Annotation

Despite a show of support for the Revolution, by the fall of 1790, the royal family and its entourage increasingly felt that the changes of the past eighteenth months had cost them their dignity and power. Unable to stop or even control the changes being wrought in the Constituent Assembly, the King and Queen began to seek assistance from other European monarchs to help them regain their lost power in France. In this letter, Louis authorizes the Baron of Breteuil, his former foreign minister who had already fled the kingdom, to find out secretly if any other government might be willing to intervene in France against the revolutionary government. The King and his court were already making moves to unravel the new constitution, even as the Constituent Assembly was still at work drafting it.

Image of the King at the Festival of Federation

Annotation

Having lived through a tumultuous year, France’s political leaders, new and old, perceived the need to foster a sense of unity among the people. The King’s more liberal ministers in particular hoped to prevent attempts to roll back the changes made since the spring of 1789 and to limit momentum for farther–reaching challenges to the monarchy. To this end, the Marquis de La Fayette organized a public pageant in Paris to celebrate the "federation" of the different regions and social groups of France. Here Louis XVI joins the construction site where the festival will take place on 14 July 1790.

The Tennis Court Oath at Versailles by Jacques–Louis David

Annotation

This amazingly rich sketch by Jacques–Louis David is one of the most famous works from the French revolutionary era. The thrust of the bodies together and toward the center stand for unity. The spectators, including children at the top right, all join the spectators. Even the clergy, so villified later, join in the scene. Only one person, possibly Marat, in the upper left–hand corner, turns his back on the celebration. And, in fact, David is commemorating a great moment of the Revolution on 20 June 1789, in which the deputies, mainly those of the Third Estate, now proclaiming that they represent the nation, stand together against a threatened dispersal.

Te Deum for the Federation of July 14, 1790 at the Champ de Mars

Annotation

A hymn written by Joseph Gossec to celebrate national unity on the first anniversary of the taking of the Bastille. Combining old and new, Gossec set a traditional Latin text to music scored for wind instruments (rather than the common organ), the sound of which carried well at the outdoor festival.

This source is a part of the

Songs of the Revolution source collection.

The New World and the Old: An American at the Opening of the Estates–General (May 1789)

Annotation

On 5 May 1789, the deputies of all three orders convened before the King as the Estates–General. In attendance, among other visiting foreign dignitaries, was the American Gouverneur Morris, who recorded his observations in a diary. In the excerpt below, Morris describes first the royal procession through Versailles and then the opening of the Estates–General itself. His description of the King reflects the broad popularity Louis enjoyed at this moment. By contrast, Morris’s sympathy for the Queen is evidently not shared by the French people present.

Marat: The King Is a Friend of the People (29 December 1790 and 17 February 1791)

Annotation

Through his newspaper, the Friend of the People, Jean–Paul Marat was one of the leading radical voices of the early years of the Revolution. Yet he also thought France had to have a king; his goal—evident in this passage—was to encourage "the people" to keep pressure on the King (and the National Assembly) to offset the influence of royal ministers and courtiers.

The October Days (1789)

Annotation

In the fall of 1789, speeches filled the air in Versailles, and a river of pamphlets and newspapers flooded Paris; however, grain remained in short supply. On 5 October, several hundred women staged a protest against the high price of bread at the City Hall. Just as in July, this traditional form of grievance took on a new meaning against the background of political events—in this case, the news that royal soldiers at Versailles had desecrated the tricolored cockade to show their contempt for the National Assembly. As the crowd grew to approximately 10,000 women, a decision was made to march to Versailles and present their grievances to the assembly and to the King. Fearing what might happen (or perhaps simply not wanting to be left out of the action), units of the national guard, led by the Marquis de La Fayette, followed them. Overnight, with help from some of the national guardsmen, the crowd of women broke into the royal palace and demanded that the royal family return to Paris to ensure a continuing supply of food. A nobleman, the Marquis de Ferrières, recorded his observations. Although a moderate, he was openly hostile to the demonstration, which he saw as chaotic and violent.

The King Returns to Paris

Annotation

From Berthault’s series of great moments in the Revolution, this engraving presents a version of events on 6 October 1789 favorable to the King. Reminiscent of orderly ceremonial royal appearances, this image suggests that the outcome stemmed from the King’s own will and that his heroic intervention prevented the massed National Guard units from firing.

Arrival of the Royal Family in Paris on 6 October 1789

Annotation

When the revolutionaries, led by thousands of women, marched to Versailles, they triumphantly seized and then brought the king to Paris, where he would live in the midst of his people. Here this image attempts to maintain a perception of royal pomp and grandeur, ignoring the reality that the king was forced against his will. Still few could fully foresee the ultimate changes underway –– that the king had lost much of his sacred aura and was now headed toward an uncertain future.

It’ll Be Okay

Annotation

Popular during the early years of the French Revolution, this song’s lively tune and repetitive chorus expressed revolutionaries’ hopefulness about the future. Singers manipulated its malleable lyrics to address a broad range of topical issues.

Oh Richard, Oh, My King!

Annotation

This aria from the Gretry opera, Richard the Lion–Hearted, was adopted by royalists during the early years of the French Revolution. The song’s accusation that the king had been abandoned by all but his most devoted followers made it a suitable counter–revolutionary anthem.

Desmoulins: A Radical’s View of the Constitutional Monarch (May 1790)

Annotation

In the spring of 1790, there was much debate in the Constituent Assembly and in the press over who should have the power to declare war or peace under the new constitution—the King or the legislature? On 22 May, the Count de Mirabeau fashioned a compromise by which the King would have power to initiate a war or agree to a peace treaty, but only with legislative approval. For many observers, this compromise was a great victory for the "people" over the crown. However, in this passage from his newspaper, Revolutions of France and the Netherlands, Camille Desmoulins, an uncompromising republican, questioned why supporters of the Revolution were content with an arrangement that left so much power in the hands of the monarch.

The King Flees Paris (20 June 1791)

Annotation

After 14 July, some of the King’s entourage had urged him to flee so that he would not have to approve a new Constitution. Aristocrats such as the Baron de Breteuil and the Marquis de Bouillé, along with the King’s brothers, who had already fled France, urged the King to join them in Austria, where they could organize a military invasion that would put an end to the changes being wrought by the assembly and restore the old regime. For two years, the King had resisted such entreaties, claiming that he should remain with the people—and moreover, that some of the changes were for the good. By mid–1791, the plans drawn up by Breteuil and Bouillé for the King’s escape, to be followed by a military invasion, were ready. As the Constituent Assembly moved toward the completion of the constitution, expected in July, the moment had come to act. Louis agreed to a plan whereby he would flee in secret, in the dead of night. To explain his action, he left a written statement to the assembly, justifying his action and proposing revisions to the existing draft of the constitution as the conditions for his return. In response, the National Assembly voted to have the King arrested to prevent him from leaving France.

Image of the King’s Departure

Annotation

This engraving depicts the King, his wife, and his children meeting at half–past midnight on 21 June 1791, about to board a carriage in which they will flee secretly from Paris toward the border. The King and Queen were poorly disguised as servants to a German noblewoman. Since most French people outside of Paris had never seen the King or Queen in person, they expected to avoid recognition if only they could get clear of the capital and the surrounding towns.

The Flight to Varennes (21–23 June 1791)

Annotation

After a late start, the royal family followed a circuitous route through a series of small towns in the countryside. However, things started to go awry near the city of Châlons, where the loyal soldiers due to escort the royal family were not to be found. The carriage continued unaccompanied to the town of Varennes, where it stopped to get fresh horses. There, a royal postmaster Drouet, who had recognized the King at an earlier stop, caught up to the carriage and had the local prosecutor, Sauce, search it. Drouet would later describe the tense scene that followed.

Arrest of the King at Varennes, 22 June 1791

Annotation

These images, all engraved and widely circulated years after the event, show four different moments of the arrest. Each successive image renders the scene increasingly dramatic. The first, a woodcut executed shortly after the event, shows the postman alone recognizing the King.

Louis XVI Stopt in his Flight at Varennes

Annotation

This romantic English painting of the King’s flight suggests only a few feet separated the King from escape.

Arrest of Louis Capet at Varennes, June 22, 1791

Annotation

This print shows an angry crowd of fervent revolutionaries breaking down doors to arrest the King.

20 June 1791, Anonymous Drawing

Annotation

In this depiction of the King’s arrest, the Queen risks her body to save her son, the crown prince.

Fleeing by Design or the Perjurer Louis XVI

Annotation

Another engraving of the King’s arrest portrays the guard apprehending Louis and his family in their flight from Paris in June 1791. From Varennes, the royal family is brought back to Paris accompanied by three deputies of the National Assembly, armed guards, and a sometimes angry crowd. Upon returning to Paris, a large and unfriendly crowd turned out to view the man now known simply as Louis Capet, no longer King of the French.

Louis Apologizes (27 June 1791)

Annotation

Louis’s unsuccessful flight polarized opinion on the powers the King should have under the new constitution. For the first time, some deputies seriously proposed doing away with the monarchy altogether and declaring a republic. Those hoping to salvage the King’s credibility created a story whereby the King had not fled but had been abducted. To this end, the King appeared before the National Assembly and apologized, indicating that he had never intended to flee the kingdom or to oppose the constitution and that he had voluntarily returned to Paris upon learning of the public outcry over his departure.

Return from Varennes, Arrival of Louis Capet in Paris

Annotation

Following his arrest, Louis and his family are returned to Paris. Large, silent crowds looked on disapprovingly.

Press Reports of the King’s Flight: Révolutions de Paris (25 June 1791) and Père Duchesne (1791)

Annotation

The news of the King’s flight and subsequent arrest provoked strong responses in the press, most of which attacked Louis as a traitor and questioned the National Assembly’s acceptance of his excuse that he had been "kidnapped." The Revolutions of Paris, previously somewhat supportive of the King, aggressively attacked him as a "traitor," "criminal," and "cannibal." Even more striking was the response of Jacques–René Hébert in his popular newspaper, Père Duchesne. Also a supporter of the King, Hébert declares that Louis is "no longer king" and not even a citizen." He suggests that the King and Queen should be imprisoned in the asylum of Charenton.

Louis Accepts the Constitution (14–25 September 1791)

Annotation

Even after the debacle of the flight to Varennes, the King’s brothers—the Counts of Provence and of Artois—continued to plot from exile for a military strike that would dispel the National Assembly before it could adopt the new constitution. Louis, however, feared civil war more than he did the prospect of becoming a constitutional monarch. He thus accepted the new constitution, swearing an oath before the National Assembly. Ten days later, Louis wrote this letter to his brothers explaining his decision and asking them to cease their efforts to organize a coup against the Revolution.

The King Accepting the Constitution amid the National Assembly, 14 September 1791

Annotation

The Estates–General, reborn as the National Assembly, finished its work by completing a new constitution. This document provided for an executive—the King—as well as a legislative body. Suffrage was male and restricted to certain economic levels. Overall, it was a moderate document that created a constitutional monarch and privileged the wealthy to a considerable degree at a time when the monarchy had discredited itself and popular classes wanted more. In retrospect, one could wonder how contemporaries believed this constitution would survive.

Marie Antoinette’s View of the Revolution (8 September 1791)

Annotation

Fears about Marie Antoinette’s intentions and actions were not baseless. Although inexperienced in the new style of politics, Marie Antoinette did see a need for help from abroad if the monarchy was to stop or reverse the course of the Revolution, which she thought to be getting out of control. She wrote this letter to her brother Leopold II, Emperor of the large Habsburg Empire in central Europe, describing the Revolution as she saw it and asking for his help to end it.

Address of the Commune of Marseilles (27 June 1792)

Annotation

In late spring 1792, a group of militant journalists and section leaders began planning an uprising that they hoped would lead to the summoning of a new assembly for the specific purpose of rewriting the constitution to create a genuine republic—thereby eliminating the King altogether. They hoped to enlist activists from the Parisian sections and armed volunteer units from the provinces who would be coming to the capital for another Festival of 14 July. Particularly noted for their revolutionary ardor were the units from Marseilles, who arrived in Paris in late June with a new battle hymn later named "the Marseillaise" and with an address to the Legislative Assembly from the municipal government.

Parisian Petitions to Dethrone the King (3 August 1792)

Annotation

Just after the Festival of 14 July, leaders of some of the more radical Parisian sections drafted, on behalf of the French nation, a petition calling on the Legislative Assembly to take emergency measures to ensure "the salvation of the people" by dethroning the King. This petition was presented to the assembly on 3 December by the mayor of Paris, Jérôme Pétion, and then printed as a pamphlet.

Image of the Attack of 20 June 1792

Annotation

By the spring of 1792, the Revolution was in crisis on several fronts—in April, war had been declared on the Habsburg Empire, uprisings were taking place in provincial cities, and the Legislative Assembly was increasingly divided over whether to consolidate gains already made or press forward with more changes. On 20 June crowds of people in Paris took matters into their own hands, invading first the Assembly and then the Tuileries Palace, where they forced the King to don a Phrygian cap and drink a toast to the health of the nation.

The Attack on the Tuileries (10 August 1792)

Annotation

In early August, the Legislative Assembly was deadlocked, unable to decide what to do about the King, the constitution, the ongoing war, and above all the political uprisings in Paris. On 4 August, the most radical Parisian section, "the section of the 300," issued an "ultimatum" to the Legislative Assembly, threatening an uprising if no action was taken by midnight 9 August. On the appointed evening, the tocsin sounded from the bell tower and a crowd gathered before the City Hall and headed toward the Tuileries Palace. As the King’s bodyguards prepared to defend him, Louis recognized that it would be more prudent to flee. He and his family escaped through a secret passage and placed themselves under the protection of the Legislative Assembly, which arrested him. A deputy, Michel Azema, describes in this letter the dramatic events that came to be referred to as the "second French Revolution."

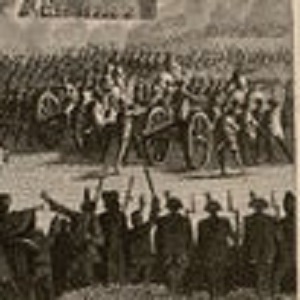

Day of 10 August 1792

Annotation

This engraving gives a ground–eye view of the action; far from an orderly operation, the "day" appears chaotic and menacing, as the inspired people face what appear to be cannons being fired by royal soldiers. This romantic image would become the predominant view of this event.

The Carmagnole

Annotation

Sharing its name with a popular dance, this song heaps scorn upon the queen (Madame Veto), believed to be a traitor, and the "aristocrats" who support her. Like "It’ll Be Okay", the simple tune of the "Carmagnole" permitted even the illiterate to learn lyrics with which to proclaim their conviction in the Revolution’s progress.

Description of the Royal Menagerie (1789)

Annotation

A common theme in libels was to compare the royal family to animals. This pamphlet parodies the Queen and her entourage as animals in a zoo, emphasizing how the courtly way of life at Versailles seemed bizarre to the rest of the French people. (The references to "royal veto" refer to the debate that took place over the power that the King should have under the new constitution to veto laws passed by the Legislative Assembly; by referring to all members of the royal family members, the pamphlet mocks the reduced powers of the crown under the new form of government.)

Marie Antoinette as a Serpent

Annotation

The Queen, never popular to begin with in France, also bore the brunt of popular anger in 1792, as seen in these images of the King, Queen, and elsewhere the entire royal family, as animals. One wonders if this dehumanization of the King and Queen might explain why they became such lightning rods for criticism and, moreover, why the entire royal family would eventually be excluded from any protection under law, at the very moment that a constitution ensuring the rights of all people was being put into effect.

Louis as Pig

Annotation

The Queen, never popular to begin with in France, also bore the brunt of popular anger in 1792, as seen in these images of the King, the Queen, and elsewhere the entire royal family, as animals. One wonders if this dehumanizing of the King and Queen might explain why they became such lightning rods for criticism and, moreover, why the entire royal family would eventually be excluded from any protection under law, at the very moment that a constitution ensuring the rights of all people was being put into effect.

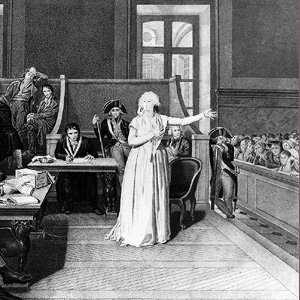

Image of the King on Trial

Annotation

When he was charged, the King could have simply refused to participate on the grounds that the extant Constitution promised his immunity. But this defense, he knew, was useless and he elected to stand on his record. Among his attorneys was the distinguished and able old regime administrator Chrétlen–Guillaume de Malesherbes. Yet in the end, political necessities and the King’s own actions led to the inevitable results: guilty and execution.

Saint–Just (13 November 1792)

Annotation

The first debate over the fate of Louis XVI concerned whether the Convention could try the King at all, and if so, for what crimes. The Constitution of 1791 had promised Louis "inviolability," meaning immunity from prosecution. One of the first speakers was Louis–Antoine Léon de Saint–Just, a brilliant, idealistic, and young Jacobin deputy. He drew on Montesquieu as well as Rousseau to argue that the legislature indeed had both the political authority under the constitution and the moral justification to judge the King.

Robespierre’s Second Speech (28 December 1792)

Annotation

As part of his defense, Louis’s lawyers had suggested the King should be judged not by the representatives of the people in the Convention but by the people themselves through a referendum. The Jacobins opposed this idea, fearing it would undermine the Convention’s position as embodying the will of the people. In his second speech of the trial, Robespierre attacks the idea of a referendum as a plot to save the King and thus undermine the Revolution.

PAINE (21 NOVEMBER 1792)

Annotation

An Englishman acclaimed as a hero of the American Revolution, Thomas Paine had been elected to the Convention by radicals in Paris. However, his international perspective and Anglo–American background (including a Quaker upbringing) inclined him temperamentally to ally with the Girondins, who were less radically republican and who looked more favorably upon the King as an individual and an institution, and who not coincidentally often spoke some English. His speech was written in English and it was read to the Convention (in French) the day after the discovery of the letters in the King’s "locked chest." Accordingly, it called for a full investigation and trial of the King, based on his policies rather than his person. Nonetheless, compassion for the individual remained a possibility.

CONDORCET (3 DECEMBER 1792)

Annotation

Jean–Antoine Nicolas Condorcet, formerly a marquis, circulated a pamphlet that was a Girondin response to Saint–Just. Although he too endorsed a trial of the King, he emphasized the necessity of following constitutional procedures, meaning that any trial had to be held in accordance with the constitution and proper legal forms.

The Pathos of Death

Annotation

Locked up in the Temple prison, there was little for the family to do but await the likely result. This image shows the grief suffusing the entire situation.

Louis’s Separation from His Family

Annotation

After hearing the verdict, the King was allowed a final evening with his family, whom he had not seen for almost a month during the trial. Twice on the evening of 20 January the King met with his wife, his son, and a daughter. For about an hour and three–quarters all told, they visited. Only at this time, three days after the verdict, was the family told of the King’s sentence. This led to a miserable scene with much weeping and kissing. The children were totally distraught when finally the father departed. Although they hoped for a final farewell in the morning, this was not to be.

Louis Leaves His Family

Annotation

What links the many scenes we have of the King and his family is the modern sensibility on display in all of them. Of course, since dates are uncertain, we must assume that several images hail from the nineteenth century. Yet all confirm the sentimentality that the twentieth century so embraces. Interestingly, this may have been quite accurate, even though this sentimentality had not been as prevalent under Louis XIV in the seventeenth century, especially in court circles. But through the entire eighteenth century, affection had insinuated itself increasingly in relations between husband and wife and parents and children. Of course, the particular situation depicted here encouraged these feelings, but the royal family would not have been a stranger to such customs. That Louis most likely genuinely loved and was devoted to his wife was certainly not typical of his Bourbon ancestors.

Last Meeting of Louis XVI with His Family at the Temple Prison

Annotation

Another version of the final meeting of the King with his family. To the left is his confessor; the figure to the right is most likely Cléry, the King’s valet.

Louis XVI and His Family (20 January 1793)

Annotation

Not shown in this or other scenes here is the fact that between the King’s two visits he ate a last meal. At this time he was denied, as was custom, a knife to avoid suicide. Louis was angered that his jailers thought he was so sinful as to take his own life.

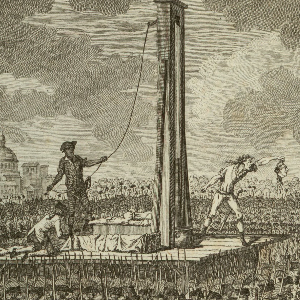

EXECUTION OF THE KING (21 JANUARY 1793)

Annotation

After voting unanimously to find the King guilty, the deputies held a separate vote on his punishment. By a single vote, Louis was sentenced to death, "within twenty–four hours." Thus, on 21 January 1793, Louis Capet, formerly King of France was beheaded by the guillotine. For the first time in a thousand years, the French people were not ruled by a monarch. The passage below, from a letter by Philippe Pinel, describes the execution—and shows great admiration for Louis’s serenity in the face of a humiliating, public death.

Hymn of 21 January

Annotation

With lyrics drawn from a Republican Ode composed by the revolutionary poet Lebrun in 1793, this hymn commemorates the execution of France's Louis XVI.

Oh Richard, Oh, My King!

Annotation

This aria from the Gretry opera, Richard the Lion–Hearted, was adopted by royalists during the early years of the French Revolution. The song’s accusation that the king had been abandoned by all but his most devoted followers made it a suitable counter–revolutionary anthem.

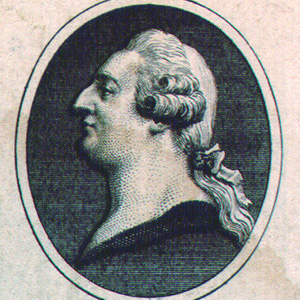

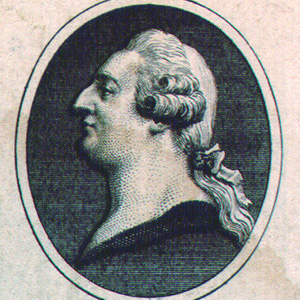

Louis XVI

Annotation

Here was the "body politic" of the old regime. Theoretically, France existed only as an entity in the body of the King. The citizens were his subjects; the geographical parts linked together only through the monarch. Robed and wigged, he was an emblem of a centuries–old regime.

Louis XVI, King of the French

Annotation

This fascinating print, likely produced before the King’s flight from Paris, takes the Louis XVI of the old regime and makes him a revolutionary with the addition of the Phrygian cap. While the engraver’s intention remains absolutely unknown, contemporaries might have seen this as mocking Louis’s new position in the Revolution. Others, less cynical, might have seen an attempt to create a monarchy living with the constitution.

Long Live Liberty

Annotation

Cartoonists extrapolated more and more on a new Louis as the Revolution went along. Here, a rather rumpled King, dressed more like a shopkeeper than a monarch, opens a cage to let liberty out. Many scholars argue that the King was already desacralized as much as a couple of decades before the Revolution. Still Louis is associated with liberty here, and this treatment was mild compared with the personal attacks and the execution that would follow.

Louis XVI, King of the French, born 23 August 1754.

Annotation

Early in the Revolution, LaFayette was among the most visible and popular leaders, in part because of his participation in the American revolution and his relationship to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and others. Further, though noble, he had been sympathetic to the Third Estate. By entwining Louis and LaFayette, this image seeks to legitimize the commander’s authority, but also to give the King more solid revolutionary credentials. It is interesting here that the King appears without the liberty cap and in his old regime finery, with only LaFayette to prove Louis was committed to things revolutionary.

Louis as a Drinker

Annotation

The arrest of the King prompted an outpouring of sentiment against Louis. Like his grandfather, Louis XV, whose early reputation as "Louis the Well–Loved" faded by the end of his long reign, Louis XVI now became the focus for all sorts of discontents. This image depicting Louis as incapable of governing himself, let alone France, reveals the depth of the scorn expressed.

Louis as a Drunkard

Annotation

This image of Louis, already altered by commoner attire and a Phrygian cap, added a raised bottle. This transformation could scarcely have been anticipated even a year or two into the Revolution.

Louis as No More Than a Man

Annotation

Part of the revolutionary undermining of the monarchy becomes evident in this profile of Louis XVI, shown here without his wig or finery.

Louis Rides a Pig

Annotation

Equestrian skills were expected of a monarch. But portraying the King mounted on a pig was most unflattering. Linking royalty to animals was a theme that emerged after the flight to Varennes.

King and Queen as Two–headed Monster

Annotation

The Queen, never popular to begin with in France, also bore the brunt of popular anger in 1792, as seen in images of the King and Queen as animals. This reversal from old regime portrayals of the monarchy is made more remarkable by the fact that beyond 1789 cartoons tried, if somewhat unsuccessfully, to integrate royalty and revolution. One wonders if this dehumanizing of the King and Queen might explain why they became such lightning rods for criticism.

Rare Animals; or, the Transfer of the Royal Family from the Tuileries to the Temple. Champfleury, 1792

Annotation

Here the events of 10 August were expressed by reducing the royal family to animals. Driven from their palace to prison, the family became no more than a group of barnyard animals. Contrast these common four–footed animals with the erect revolutionary whipping them along.

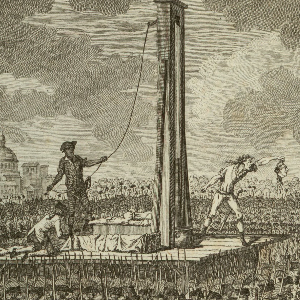

The Tragic End of Louis XVI

Annotation

As 80,000 crowded into the square to watch the execution of Louis XVI, they cannot have been unaware that the guillotine sat where a statue of Louis XV had been. Here Sanson, the executioner, snatches the detached head of Louis XVI to show to the crowd. He leans forward with approving eagerness. If the head of the King was the most recognizable old regime symbol, then the demise of that symbolic system becomes now complete. Waving on a pike, facing the King, is a Phrygian cap, now no longer placed on his head, as in other prints. In this way the engraver indicates a final severance of a complicated compromise.

Commemorating the Revolution on Chinaware

Annotation

A Positive View?

Annotation

This composition of the scene, in which a helpless Louis seems to be looking upward to heaven with his confessor, communicates humility. The executioners are relatively passive, leaving the King and confessor center stage. This reveals that in mortal death, the King had a chance to look better than his tormentors. Although this print was undoubtedly produced significantly after the fact, contemporary spectators also might have felt this moment of moral superiority available to the victim. As sentimentality became more prevalent in the eighteenth century, sympathy for the accused on the scaffold had grown, so that authorities had increasingly taken executions out of the public eye. Perhaps, it is likely that Louis at least realized a measure of this same concern. And possibly Sanson’s exuberance after the execution when he eagerly held aloft the King’s head, as well as a prior decision to call for a drum roll to drown out the King’s attempts to address the crowd, were meant to erase any empathy for his condition.

Louis XVI, King of France, born 23 August 1754, beheaded 21 January 1793

Annotation

Louis quickly became a matyr to the royalist cause, as this and other memorials indicate.

Hell Broke Loose, or, The Murder of Louis

Annotation

In this English image, as the King’s head is about to fall into the executioner’s basket, bats out of Hell emerge, symbolizing the Revolution. At the same time, God’s favor seems to fall on Louis through a shaft of light coming from heaven. From the first, some English, especially Edmund Burke, were skeptical, indeed critical of the Revolution, and the numbers grew over time. In addition, the English had a thriving group of political cartoonists. These two factors helped produce some very interesting counterrevolutionary images.

The Blood of the Murdered Crying for Vengeance

Annotation

Yet another English image promising that the death of Louis will bring havoc on the French Revolution. This engraving indicates that the very blood of the King requires vengeance.

The Queen Exhausted

Annotation

An image produced well after the Revolution shows a Queen, assaulted by the gaze of the people, controlled by the soldier, and tentative in her stance and appearance.

"The Royal Orgy" (1789)

Annotation

In 1789, with the collapse of old regime censorship as well as a sense of liberation from traditional moral constraints, printed libels against the Queen became both more common and more intense. An example of this greater intensity is this light opera, with raunchy lyrics set to popular tunes. Not intended to be performed, the pamphlet spoofs the Queen’s great interest in opera and her supposedly even greater interest in the sexual prowess of some of her courtiers. As with the pornographic libels of the old regime, the printed accounts of her trysts with the Count of Artois and the Duchess of Polignac had no basis in fact, but they were consistent with the popularly held view of Marie Antoinette as out of touch with her people, self–interested, and a hindrance to the proper government of France, because of her uncontrollable lusts for power, luxury, and sex.

DESMOULINS ATTACKS THE QUEEN (JUNE 1791)

Annotation

This article appeared in the newspaper Revolutions of France and Brabant, under the headline: "Horrible maneuvers of the Austrians at the Tuileries Palace to bring civil war to France . . ." and discusses various rumors making the rounds that the King would soon flee France and initiate an invasion led by former aristocrats to undo the evolution. Camile Desmoulins’s reference to the "Austrian Committee" implied that Marie Antoinette was conspiring with other members of her Habsburg family who ruled in Austria.

THE QUEEN AT THE OPERA (JULY 1792)

Annotation

Since the seventeenth century, French monarchs had been great patrons of the theater and opera, which they regularly attended in Versailles and Paris. Such performances had been occasions to appear before their subjects, aristocratic and common, and to receive public acclaim. Although Louis XVI showed much less interest in theater–going than his predecessors, his Queen had been an enthusiast, especially of light opera. This text describes a visit by Marie Antoinette to the Italian theater, at which she was poorly received by the audience. The account is written by Grace Dalrymple, an English nobleman in Paris during the Revolution, as a report to the king of England.

THE QUEEN’S DEFENSE (14 OCTOBER 1793)

Annotation

Seven months after the execution of the King, shortly after the declaration of "Revolutionary Government," the Convention turned to the rest of the royal family. Fearing that Marie Antoinette and her son, the nominal King, would provide rallying points for royalists within France and abroad, a Revolutionary Tribunal indicted Marie Antoinette and her children for treason. Two attorneys were assigned to prepare her defense, and one describes the situation here.

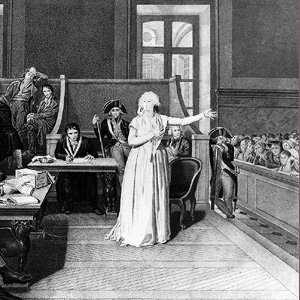

Trial of Marie Antoinette of Austria

Annotation

Some months after the execution of her husband, Marie Antoinette found herself in the dock of the public prosecutor, Antoine Quentin Fouquier–Tinville. The intervention of the radical journalist Jacques–René Hébert had pushed her case to the top, and she was accused most notably of immorality and treason. She defended herself bravely and calmly, as the above image suggests. But the judgment was never in doubt, as the revolutionaries had always doubted her. And acquittal in these conditions was difficult at best. After a two–day trial, she was convicted and executed the next day, 16 October 1793.

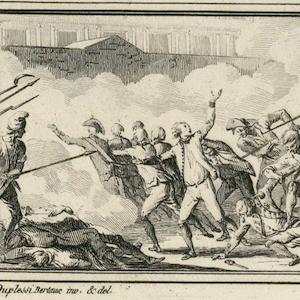

Image of the Queen’s Defense

Annotation

The trial of the Queen is here depicted in a tinted engraving by Jean Duplessi–Bertaux as part of his series of Historical Scenes of the French Revolution. Although it refers to her as "Marie Antoinette, the Austrian," the etching portrays her somewhat sympathetically, showing her in a graceful pose with a concerned look on her face amid a hostile prosecutor, judge, and soldiers.

EXECUTION OF THE QUEEN (16 OCTOBER 1793)

Annotation

At the conclusion of her trial, the Queen was found guilty and sentenced to death. The newspaper of record, the Moniteur, reports the Queen’s response to the verdict and her execution the next morning with a good deal of sympathy and respect.

Execution of Marie Antoinette (16 October 1793) at the Place de la Révolution

Annotation

This postcard in English and French does show the broader scene at the execution of the Queen. Before the guillotine stands Marie Antoinette with Sanson, the same executioner who had dispatched her husband ten months before. Surrounded by soldiers, and tens of thousands of onlookers, she awaits the moment of death. Also on the platform is Marie Antoinette’s confessor. The execution, like that of her husband, took place at the Place de la Révolution, recently renamed from Place de Louis XV (currently Place de la Concorde). Dominating the entire scene was a giant statue of Liberty sitting on a pedestal that once held a statue of Louis XV. In Liberty’s right hand is a pike while she wears a Phrygian cap. This reshaping of the monarchical square seems quite consistent with the elimination of the Queen.

The Queen of Louis XVI King of France at the Guillotine, 16 October 1793

Annotation

An idealized portrait of Marie Antoinette at the moment of death. Unlike the pale, aged woman the contemporaries observed, this later print memorialized a beautiful, absolutely pure, woman. While in life she had been assailed as a lesbian, a pedophile, and an adulteress with men, here she is being depicted as nearly a saint. Indeed, a great problem that the revolutionaries had was that, as they executed those they thought guilty, they also referred them to martyrdom and ultimately to a good chance for rehabilitation.