Short Teaching Module: Premodern Chinese Maps and the Global Maritime World

Overview

Premodern Chinese maps offer fascinating sources for teachers and students of world history. As historian Elke Papelitzky explains, these maps can reveal much about the world view of the mapmakers and their audience in China and they also serve as example of how knowledge and skills spread from region to region in the period. Using three such maps, Papelitzky notes details that illuminate much about Chinese maritime history in the 1300-1700 period.

Essay

Premodern Chinese maps can be used to study China’s global and maritime connections in different ways. Maps showing non-Chinese regions can show the world view of the mapmakers. Regions that were mapped repeatedly can be assumed to have closer ties to China. Mapmakers often integrated mapmaking practices from elsewhere and if we can identify these, the maps are evidence of the history of the exchange of knowledge. These points often cannot be separated, as Chinese mapmakers learned of regions abroad from non-Chinese actors (and vice-versa). Given China’s close relations with regions across the ocean, these maps are also a rich source for studying China’s maritime history.

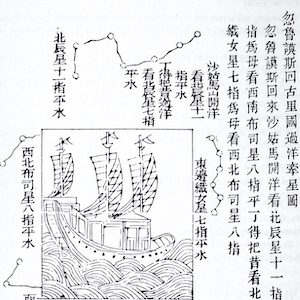

Scholars in Europe and Northern America have been studying Chinese maritime maps since the 1950s, most notably J. V. G. Mills. Many of his findings still influence our understanding today of Chinese maps focusing on oceanic space. The maps he focused on are coastal maps that depict the coast as a long strip (either on a scroll if in manuscript form, or as individual pages in a book). Most of these only map the coast of China, but one prominent example maps the coast from China to eastern Africa. This map, usually called “Zheng He map” (older literature also refers to it as the “Mao Kun map”) incorporates information from the seven expeditions to the Indian Ocean led by Zheng He 鄭和 (1371–1433) during the early fifteenth century. It illustrates China’s connections with the Indian Ocean world during the fifteenth century.

One notable feature of the Zheng He Map is that it draws lines in the ocean that designate sailing routes. These lines are annotated with information on how to use the compass. The Zheng He map also marks the time needed to travel between the indicated points. This kind of information is usually found in route books (also known as “rutters”), which are sailing instructions circulated as text usually without images. This, however, does not necessarily mean that the maps were used for sailing. We might be inclined to think of them as such, especially when we consider navigating practices of European sailors. However, in the Chinese context evidence for actual practical use of maps aboard ship is thin. No map is known today that was without doubt used on a ship by pre-modern Chinese navigators and the few descriptions we have are ambiguous and might also point to sailors relying on rutters or drawings of islands (“views”). Instead, the extant maps often feature in books that connect them to military purposes such as coastal defense or serve to satisfy the curiosity of the learned elite.

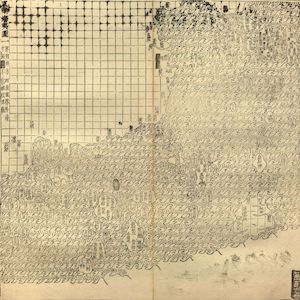

In 2008, Robert Batchelor discovered what is now known as the Selden Map in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. This map caught the attention of many scholars, in Europe, America, and Asia alike, and up to today is probably one of the most discussed maritime Chinese maps. The manuscript shows Southeast Asia, marks place names in Chinese, and like the Zheng He Map adds lines in the ocean to mark sailing routes. Not many concrete details are known about this map. Its origins are not as clear as in the case of the other maps. It was produced in the context of merchant activities probably somewhere in Southeast Asia in the early seventeenth century (the exact place and date of origin is contested). This map shows us that it is not always easy or possible (or even sensible) to assign a single country of origin to objects.

Aside from these maps focusing on maritime space, we can also draw conclusions about China’s maritime connection through maps of China that mark non-Chinese regions. The earliest extant Chinese maps that show maritime regions from the twelfth century do not map countries based on their shape but mark them as small circles or rectangles in the ocean next to China, which is usually mapped in more detail. For the mapmakers, only the fact that these countries existed was important. The shape, and their location relative to each other was unimportant, as were the names and locations of cities in these countries. The practice of mapping maritime space in this way continued well into the nineteenth century.

Over time the regions and selection of countries changed, partly influenced by China’s changing relations with other regions of the world. The labelling with place names of the islands and not their shape is important to understanding the space. This means that the choice of space can be looked at detached from the shape of the islands/continents.

One of the most fundamental questions we should ask about these maps (any map for that matter) therefore is: Which space and region does it depict? The answer to this question is not always intuitive, as the map does not follow map conventions we understand as standard today. To our eyes today, the Selden Map looks much more familiar than the Zheng He Map and we can identify islands and landmasses just by looking at the Selden Map but not the Zheng He Map.

However, to fully understand Chinese maps, we need to let go of a singular idea how maps should look like based on our understanding today such as that maps should be oriented to the north, that the most important indicator of “accuracy” is the shape of the coastlines, or that a map should have a fixed scale. Matthew Edney recently argued that these assumptions of what makes a map are only an “ideal” of cartography, and these questions are true not only for Chinese maps, but for all maps. We should keep this in mind and consider the historical context, time, and place the maps were made, especially when it comes to Chinese maps that might seem much more inaccessible and strange to non-Chinese readers.

Mostly, Chinese maps mark China’s most immediate neighbors and they appear on maps that largely focus on China: Japan, Korea, the Ryukyu kingdom, Annam (Vietnam). Other countries in Southeast Asia such as Siam (Thailand), Melaka (in what is now Malaysia), Java, and various places on the Philippines also appear relatively frequently. When the political situation in these countries changed, the place names on the Chinese maps were updated and the composition of names could slightly change. “Luzon” for example, started appearing on Chinese maps in the late sixteenth century in connection with the increased importance of Manila in global trade networks.

As these examples show, Chinese maps can give us much information into the global maritime network China was part of. The Selden Map shows that even in recent years, objects can be found that have a great effect into our understanding of Chinese mapmaking practices and the map’s functions, but even the maps we already know of today, can tell a varied and interesting story of the maritime word that still waits to be explored in full.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Batchelor, Robert. London. The Selden Map and the Making of a Global City, 1549–1689. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Brook, Timothy. Mr. Selden’s Map of China. Decoding the Secrets of a Vanished Cartographer. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2013.

Edney, Matthew H. Cartography: The Ideal and Its History. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Mills, J. V. G. Ma Huan. Ying-Yai Sheng-Lan. The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores [1433]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970.

Nie, Hongping Annie. The Selden Map of China. A New Understanding of the Ming Dynasty. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2019.

Po, Ronald C. The Blue Frontier. Maritime Vision and Power in the Qing Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Ptak, Roderich. ‘Selected Problems Concerning the “Zheng He Map”: Questions without Answers’. Journal of Asian History 53.2 (2019): 179–214.

Credits

Elke Papelitzky obtained her PhD in history from the University of Salzburg and is currently a postdoc at KU Leuven in Belgium. Her research focuses on knowledge transfer and the perception of the world of Japanese and Chinese literati as seen in geographical sources, both written and in the form of maps. She is now part of the project TRANSPACIFIC led by Angela Schottenhammer, which has received funding from the ERC under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (Grant Agreement no. 833143). As part of this project, she will look at Chinese and Japanese perceptions of the Philippines and the impact of the transpacific trade on geographical knowledge. Elke Papelitzky is the author of Writing World History in Late Ming China and the Perception of Maritime Asia (Harrassowitz, 2020) and of several articles and book chapters.