Short Teaching Module: Nineteenth-Century American Trade on Zanzibar

Overview

Although American merchants often fade from historical narratives after the eighteenth century, they remained influential actors in the United States and abroad. As western expansion and industrialization reshaped the nation’s economy, American traders dispatched voyages around the world in search of new opportunities. During the 1820s, businessmen from Salem, Massachusetts reached the island of Zanzibar. Over time, Americans successfully integrated themselves into the island’s thriving economy, developing close relationships with established Indian and Omani merchants. Through innumerable negotiations, these men co-created a highly practical and profitable commercial system that melded key aspects of Atlantic and Indian Ocean commercial practices. In the process, they linked the trajectories of New England and the Western Indian Ocean for over fifty years.

Essay

While globalization is often considered a distinctive feature of the twentieth century, expansive commercial exchange has bound together disparate peoples for millennia, significantly effecting the trajectory of human development. In my research, I consider globalization as a lens of analysis instead of a particular series of events. By taking a more global approach, one that is less dependent on modern political boundaries, historians can better capture the realities of historical actors who experienced, and imagined, the world much differently than we do today. By taking a broader perspective, historians can follow sources wherever they lead, discovering influential relationships that have been overlooked or dismissed as mere oddities. While a casual observer would never connect Salem, Massachusetts and Zanzibar today, during the nineteenth century these places, and their inhabitants, were closely linked by trade, significantly impacting each community.

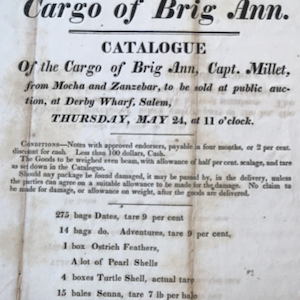

After twenty years of unparalleled commercial growth, American merchants faced a litany of challenges in the early nineteenth century. As the Napoleonic Wars convulsed Europe, Britain and France targeted American vessels with growing frequency. In an attempt to remain neutral, the United States implemented a short but devastating ban on international trade in 1807. The policy delayed but did not prevent war. For nearly three years, the War of 1812 severely curtailed trade. When peace finally came, American merchants had to contend with a small but growing manufacturing industry. Pushed to the brink, American merchants adapted, seeking out new ports and experimenting with new cargos. During the 1820s, the first American ship reached the East African island of Zanzibar. For the next fifty years, dozens of American ships made the voyage, carrying cotton cloth, guns, gunpowder, brass wire, and specie before returning stocked with ivory, gum copal, cloves, and hides.

During the early 1800s, the Omani Empire was one of the Western Indian Ocean’s leading commercial and naval powers, serving as an intermediary between Arabia, India, and East Africa. Under the reign of Said bin Sultan (1806-1856), Oman consolidated control over a handful of East African ports including the island of Zanzibar. Although the Sultan took an active interest in commercial affairs, controlling his far-flung territories often depended on a careful policy of benign neglect. On Zanzibar, Said delegated significant financial authority to the island’s Indian custom master, Jairam Shivji. Under Said and Shivji, Zanzibar emerged as a leading commercial center that attracted Arab, Indian, East African, European, and American merchants.

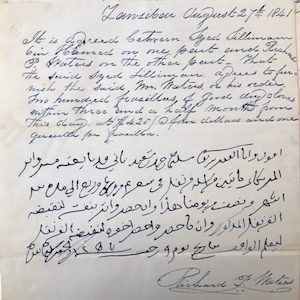

Upon arrival, American merchants faced numerous difficulties. Unable to speak the island’s commercial languages—Swahili, Gujarati, and Arabic— American traders struggled to communicate effectively. Omani officials also levied a variety of commercial fees and periodically curtailed access to Zanzibari commodities. After a few fitful starts, the United States and Oman negotiated a “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” that took effect in 1834. The treaty limited all taxes to a five per cent import duty and called for the establishment of an American consulate. In early 1837, the first American consul, Richard Waters, arrived on Zanzibar. While the treaty offered Waters a starting point, it left much unsaid. Over time, Waters came to realize that commercial success depended on two main factors: establishing a shared framework for commercial transactions and forming strong personal relationships with leading merchants.

From the very start, American trade on Zanzibar raised a number of basic questions. What goods would sell? What currencies were acceptable? How would commodities be evaluated and measured? Each time a transaction took place, American, Indian, and Arab merchants inched closer to a mutually acceptable set of standards. These frameworks can still be seen in surviving bilingual commodity contracts such as the second primary source included with this module. Rendered in English and either Arabic or Gujarati, the agreements’ formulaic clauses depict the careful melding of Indian Ocean and Atlantic commercial practices.

Although American merchants won some concessions, they were often compelled to accept prevailing practices to ensure access to Zanzibar’s commodities. Consider currency. Throughout this period, the Maria Theresa Thaler, an Austrian silver coin, served as the official currency of the Omani Empire. Its frequent scarcity, however, forced merchants to find alternatives. To fill the gap, American traders imported large amounts of North American silver. While Zanzibar’s merchants generally accepted the specie, they forced their American counterparts to accede to an unfavorable exchange rate for decades.

Most compromises were highly practical. For example, American and Zanzibari merchants generally adopted the same measurements for most commodities; Indian Ocean goods used local units while American merchandise retained their own units. Cloves, ivory, and gum copal were sold by the “frasilah” while goat hides were measured by the “corgee.” Even in Gujarati texts, American cotton and guns continued to be referred to by the bale and box respectively. By adopting foreign units as needed, both American and Zanzibari merchants simplified their transactions and minimized conversion errors. With hundreds of thousands of pounds of commodities involved, a small rounding error could threaten a voyage’s profitability.

While shared commercial standards played a crucial role in facilitating trade, forming personal relationships with Zanzibar’s leading figures proved equally important. Richard Waters’s commercial success depended heavily on Said bin Sultan and Jairam Shivji’s good will. Over time, Waters also built rapport with a handful of influential Arab merchants who often entertained him on their large plantations. While Waters coordinated his commercial affairs closely with Jairam Shivji, another American merchant, John Webb, also recounted numerous social interactions with the custom master. The two men frequently walked around town in the evenings or went for canoe rides. Webb also attending numerous social events held by the island’s small Indian community including a monthly ritual to welcome the new moon and a dance performance at Shivji’s home (Entries for June 30, 1851 and July 29, 1851, Diary of John Felt Webb, MSS 0.145, Peabody Essex Museum).

Although isolated from their countrymen, Zanzibar’s small American community imported their prevailing views of race, religion, and civilization as surely as they did commodities. To race-obsessed Americans, Zanzibar offered a confounding mix of peoples. As one American noted, “the inhabitants are of various races, from the light-complexioned Hindoo to the darkest African: Banyans, Parsees, Malays, Bedouin Arabs, Oman Arabs, [Swahilis], Africans, &c…” (John Ross Browne, Etchings of a Whaling Cruise (New York City, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1846), 335.) For the most part, Waters, Webb, and their peers were willing to rub shoulders with the island’s leading Arab and Indian merchants in order to make money. Nonetheless, they remained critical of all of Zanzibar’s inhabitants, including Said bin Sultan. In one instance Waters’s successor, Charles Ward, noted that the Sultan was a “Mohomedan and an Asiatic,” and that “there is nothing so convincing to Mohamedans & Asiatics as a display of physical force.” (Charles Ward to George Abbot, March 13, 1851, in Norman Robert Bennett and George E. Brooks, New England Merchants in Africa: A History through Documents, 1802 to 1865 (Boston University Press, 1965).)

Although Americans penned a series of derogatory depictions of Zanzibar’s Arab and Indian inhabitants, they reserved special contempt for the island’s large East African population. As one visiting American recounted, “Captain Webb, of Salem… described [East Africans] as an indolent, superstitious, and degraded race, extremely treacherous, and possessing no taste whatever for the refinements of civilized life. In their manner of living they are little better than mere brutes.” (Browne, 358) While nineteenth-century Americans were willing to make a variety of commercial and cultural concessions to enrich themselves, entrenched racism and a broad sense of cultural superiority constrained cross-cultural interactions.

Primary Sources

Credits

Josh Morrison received his PhD from the University of Virginia in 2021. He currently works as a postdoctoral research scholar at Columbia University. He studies the commercial practices of American merchants and their foreign counterparts, tracing the United States’ integration into global trade networks during the nineteenth century. By examining commercial ties between Salem, Massachusetts and the East African island of Zanzibar, his scholarship explores how international trade shaped the economic and political trajectory of the United States and the Western India Ocean.