Short Teaching Module: Global Microhistory and the Nineteenth-Century Omani Empire

Overview

In their primer essay, Jessica Hanser and Adam Clulow note how scholars of global microhistory explore relationships between macro and micro, deep structures and contingency, and big state actors and minor players. This module uses sources from the nineteenth-century Omani Empire (see first comment above), which stretched from Zanzibar north to the Persian Gulf, to craft a microhistory that disrupts a triumphalist narrative of the rise of the British Empire. These sources help put local people, including Sa‘id bin Sultan, the leader of the Omani Empire, at the center of the story.

Essay

The microhistory approach is inspired by historians such as Tonio Andrade, Francesca Trivellato, Emma Rothschild, and Margot Finn, whose works seek to infuse depictions of global historical transformations with, in Andrade’s words, “the human dramas that make history come alive.”

In meeting Andrade’s challenge, we might turn to one of the original microhistorians, Carlo Ginzburg, and his concept of “clues” in history. Ginzburg’s approach was like that of a detective solving a puzzle, in that a historian ought to look as much for the most negligible details in sources as for the more obvious, and numerous, takeaways. After interviewing Ginzburg, Maria Pallares-Burke characterized his concept of “clues” as stressing “the importance of the apparently insignificant detail, the seemingly trivial phrase or gesture which leads the investigator…to make important discoveries.”

Framing history as being like detective work not only makes for a more captivating classroom, but it also makes for more captivating scholarship. It encourages historians to augment broad structural changes with fine-grained details – details that are easily overlooked, perhaps considered interesting but inconsequential. Passing remarks, doodles in a diary, even decorations in a house can all contain clues for enriching our understandings of world transformations in the making, and help illuminate the persons who helped make those transformations. Even the history of something as broad and structural as the emergence of global capitalism can be enhanced, with scrutiny of details allowing for rethinking received narratives, by looking at such clues.

What might this look like in practice?

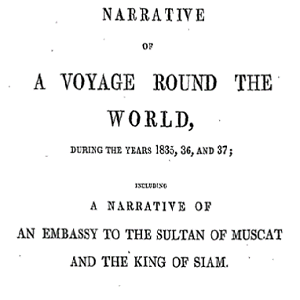

In the summer of 1834 New England merchant Edmund Roberts sailed to Muscat. Roberts was there as part of an official delegation sent by President Andrew Jackson to negotiate a treaty with Sa‘id bin Sultan. In a memoir, one member of the American delegation remembered how he had seen two paintings hanging in Sa‘id’s residence that seemed at odds with the rest of the ornate Persian, Swahili, Indian, and Chinese décor. Hanging prominently in the room reserved for diplomatic meetings were prints depicting dramatic scenes from two American naval victories over the British in the War of 1812.

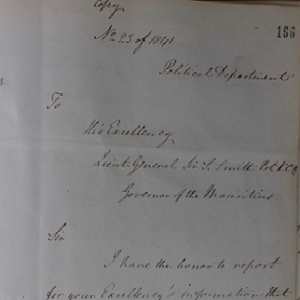

The remark in the American delegate’s memoir about the paintings might seem insignificant until one connects it to another source from nearly a decade later. In 1841 Atkins Hamerton, the first British consul, arrived in Zanzibar. He met with Sa‘id, took stock of the British situation in East Africa, and then professed to the Bombay Government: “I am sorry to inform Your Excellency, that our influence at Zanzibar is in the lowest possible scale, there being a strong party in favor of the French and American interests and more particularly the latter.” He continued to describe how, during his meeting with Sa‘id, he had noticed two paintings prominently displayed in “richly gilt frames.” He griped in his letter to Bombay how the paintings depicted American naval victories, with the American flag being hoisted above humiliated and defeated British sailors.

The paintings must have held some value for Saʿid. By 1841, when Hamerton met with him, Saʿid had moved them from his palace in Muscat to his beach-front palace in Zanzibar. The two paintings, however, are no longer in what remains of Sa‘id’s residence in Zanzibar. We only know they were there in the mid-1800s because of one brief remark in a relatively obscure American memoir and one sentence in one letter among millions that comprise the nineteenth-century records of the British National Archives. But we can interpret these paintings as a clue for understanding global connections and transformations in the mid nineteenth century.

The nineteenth century is typically depicted according to a triumphalist narrative centered on the rise of the British Empire. The Indian Ocean region, the vast arena connecting Africa to China and all parts in between, has been described, for example, as a “British Lake.” Zeroing in on two paintings depicting humiliating British defeats hung in the diplomatic reception room of the leader of one of the most flourishing commercial entities in the mid nineteenth century reminds us, however, that as historians and educators we should always interpret a particular historical period from the perspective of that period. We can use the clue of these paintings, then, to unpack a vast and complicated history pushing back on narratives of British hegemony and showing how the British were aware of their own commercial weaknesses.

In fact, well into the nineteenth century the dominant commercial, social, and political actors throughout the Indian Ocean arena remained local African, Arab, Persian, Indian, and Asian peoples. The paintings serve as a keyhole through which we can look to begin unpacking yet another tremendously vast area of historical inquiry: augmenting the agencies of local peoples in their own histories, rather than telling that history through an Anglospheric lens. Some might argue that the paintings Sa‘id had hung in his residence just means that one Anglo power (the Americans) were replacing another Anglo power (the British) in the Indian Ocean – still leaving us with a rise-of-the-West narrative. However, when combined with other sources, the paintings help us to see how Sa‘id exploited the British-American rivalry throughout his empire to ensure that the dominant commercial actors in the western Indian Ocean remained local Africans, Arabs, and Indians.

To understand this more, we might go further back in time to look at another clue.

For millennia, the Indian Ocean world had been connected into a rich social and commercial tapestry, fueled by trade in fine consumer goods like ivory, pearls, silk, spices, perfumes, porcelain, and more. As Europeans learned to travel to this part of the world, these same goods fueled a relatively new rise in European consumerism.

How do we interpret this vast historical transformation, of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans merging into one oceanic marketplace? Conventional depictions of this world historical process put Europeans in the driver’s seat. As Immanuel Wallerstein put it, for example: “Incorporation into the capitalist world-economy was never at the initiative of those being incorporated.” Decades later, Sven Beckert echoed Wallerstein when he wrote: “The insertion of armed European merchants into the Asian trade…slowly marginalized these older networks, as they muscled the once dominant Indian and Arab traders out of many intercontinental markets.”

A fine-grained reading of sources from the period under study, however, helps push back against such narratives. In 1765, one young British merchant sailing through the Indian Ocean wrote home to his father, telling him how doing business there was a “sure path” to wealth. He added: “A moderate share of attention, and your being not quite an idiot, are ample qualities for the attainment of riches.”

The young man’s exhortation to not be an idiot might make some readers laugh, but it is a critical clue for more sensitively interpreting this history. Contrary to notions of a unitary, one-way narratives of European incorporation of non-European peoples and systems, newly arriving American and European merchants, to borrow from Alison Games, had to carefully navigate the Indian Ocean world, learning to assimilate to its norms and practices and acquiesce to its own indigenous structures of power.

To link this clue from 1765 with the clue of Sa‘id’s paintings from nearly a century later: one of the reasons it can be argued that the Americans bested the British in commercial terms was that they more effectively ingratiated themselves into local commercial and political networks. Arabs, Indians, East Africans, and other local Indian Ocean peoples used Americans and Europeans as financial intermediaries – minority middlemen – in augmenting their own commercial standings and incorporating the relatively newly emerged North Atlantic into the ancient Indian Ocean commercial space.

Carlo Ginzburg’s concept of clues provides one intriguing way for historians to answer Tonio Andrade’s call for filling in abstract, structural historical narratives with the human dramas that comprise those structures. The historical hunt for easily-overlooked clues allows historians – in the classroom and on paper – to celebrate the complexity of history and its actors, rather than to simplify it, to augment the voices of those that have been lost to the privilege of writing history backward, and to remember that, in the end, as historians we are talking about human beings – in the past and as part of who we are today.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. New York: Knopf, 2014.

Games, Alison. The Web of Empire: English Cosmopolitans in an Age of Expansion: 1560-1660. London and New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Ginzburg, Carlo. Clues, Myths, and the Historical Method. Translated by John and Anne C. Tedeschi. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2013.

Ginzburg, Carlo. “Clues: Roots of a Scientific Paradigm.” Theory and Society 7 no. 3 (May 1979): 273-288.

Pallares-Burke, Maria Lucia G. The New History: Confessions and Conversations. Camrbidge, UK: Polity Press, 2002.

Roberts, Nicholas Paul. A Sea of Wealth: Sayyid Saʿid bin Sultan, His Omani Empire, and the Making of an Oceanic Marketplace. Ph.D. Dissertation. University of Notre Dame. Notre Dame, IN, 2021.

Roberts, Nicholas Paul. “‘They Never Thought a Yankee Could Do So’: Sayyid Saʿid bin Sultan and the Anglo-American Rivalry in the Indian Ocean.” In Oceanic Circularities: Mobile People and Connected Places in the Indian Ocean. Edited by Rogaia Abusharaf and Uday Chandra. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, forthcoming 2022.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Second Era of Great Expansion of the Capitalist World-Economy, 1730s-1840s. The Modern World-System, vol. 3. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

Credits

Nicholas Roberts is Assistant Professor of History at Norwich University. In academic year 2022-2023, he will be the Inaugural W. Nathaniel Howell Postdoctoral Fellow in Arabian Peninsula and Gulf Studies in the Corcoran Department of History at University of Virginia. While there, he will complete a book manuscript based on his dissertation, which won the John Highbarger Memorial Dissertation Prize from the University of Notre Dame, the Gwenn Okruhlik Dissertation Award from the Association for Gulf and Arabian Peninsula Studies, and Dissertation Award Honorable Mention from the World History Association. He earned his Ph.D. in History from the University of Notre Dame, where he was a Presidential Fellow.