Long Teaching Module: Women and the Puerto Rican Labor Movement

Overview

In December 1898, at the close of the Spanish-American War, Spain surrendered control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Guam to the United States. Though Cuba achieved nominal independence in 1902, in 1917 Puerto Rico assumed the status of an American territory, which afforded Puerto Ricans U.S. citizenship and the right to elect their own legislature, but not the full benefits of statehood. When American forces occupied the island in 1898, the Puerto Rican economy and politics underwent a shift that had implications for labor relations. For instance, the introduction of large-scale agriculture produced opportunities for some women to work as cigar strippers. Indeed, women’s participation in this new economic order gave them the same economic opportunities as men. As changes in the economy took place, women joined their male partners in the struggle to improve working conditions. Thus, women were active participants in and key members of the labor movement from the very beginning. However, as their role in the economy became more prominent, working women became targets of gender and racial discrimination, and their struggle in many instances was interwoven with issues of race, gender, and class. Viewing women solely as workers in the agricultural economy, some industrial managers attempted to limit and control Puerto Rican women’s reproductive choices in order to increase the efficiency of the economic system.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, and essay prompts relating to the twelve primary sources.

Essay

Industrialization and Women in the Workforce

Traditionally, agriculture formed the base of the Puerto Rican economy. Workers from the tobacco and sugar plantations formed gremios, or guilds, which are considered the first attempts at labor organizations. American control brought large corporations and new modes of factory production, which displaced the traditional workshops settings and artisanal apprenticeships. A focus on mass production undermined the quality-oriented mode of production of the artisans.

In 1929, the Wall Street stock market crash precipitated what came to be known as the Great Depression in the United States. Not isolated to the United States, the stock market crash was part and parcel of a worldwide economic downturn. The depression had devastating effects on the island, creating widespread hunger and unemployment that lasted for over a decade. Many banks could not continue to operate. Farmers fell into bankruptcy. As part of his New Deal efforts to restore economic stability, President Roosevelt created the Puerto Rican Reconstruction Administration (PRRA), which provided for agricultural development, public works, and electrification of the island. This improved infrastructure helped to bolster the Puerto Rican economic situation and relieve some of the devastation from the depression.

Adopting the slogan “Bread, Land, and Liberty,” in 1938 the Partido Popular Democrático (Democratic Popular Party) was founded under the leadership of Luis Muñoz Marín. In the insular government, Muñoz Marín had served as a member of the local Congress, as the President of the Puerto Rican senate, and eventually as the first elected Governor of Puerto Rico. In its beginnings the Partido Popular Democrático favored independence for the island. In addition, Muñoz Marín both supported the increased industrialization that American companies were bringing to the Puerto Rico and was an advocate for workers’ rights.

During this increasing industrialization, women took on a more prominent role in the new economy. The demands in the needle industry forced women to leave their homes and work in factories. They worked as seamstresses for low wages. In 1934 Eleanor Roosevelt visited the island and wrote about women’s work in the needle industry in her column “Mrs. Roosevelt’s Page” for the magazine Woman’s Home Companion. Roosevelt also criticized the employment system of those factories. She observed that seamstresses were paid “two dollars a dozen” for making handkerchief that took them “two weeks.”

These types of demands and labor exploitation made women realize that they were as oppressed as men. Thus, it is not surprising that women joined the labor movement along with their male partners as a way to resist economic exploitation.

Organizing

Changes in the Puerto Rican economy altered the relationship between the worker and the economy. The result was that the artisan class developed a more defensive attitude, not only toward industrial capitalism, but also toward the political influences that American companies exercised on the island.

The labor movement in Puerto Rico organized as a political party and adopted socialist ideology to balance the power of U.S. corporate capitalism. In addition, after the United States took control of the island, workers saw an opportunity to join labor organizations such as the American Federation of Labor. Workers’ attempts to combat socioeconomic oppression were facilitated by their socialist critique of the working environment.

Organized workers used newsletters and newspapers as tools of information and empowerment. Headlines and announcements from union newspapers demonstrate that the local labor movement considered women’s issues important. Collectively, this focus on women’s issues allowed female workers from around the island to feel united, and like they had a stake in the labor movement, and the political party that represented them.

It is important to point out here that the union recognized women not only as factory workers, but also as equal partners in the struggle for fair treatment—a struggle that occasionally brought them into conflict with the police. Women strikers, however, did not always behave within the bounds of traditional gender norms. There were instances in which some women strikers “went out of control” and were put in jail.

Reproductive Issues

Though female workers were active participants in the labor movement alongside male workers, primarily women bore the brunt of the coercive and discriminatory reproductive restrictions championed by American industrialists and social workers. From their initial arrival on the island, the Americans were concerned about “public order.” Often this alarm was articulated in terms of a concern about “overpopulation”—the average Puerto Rican family included five to six persons—and a perceived lack of self-control on the part of working class and poor Puerto Ricans.

In 1917, with the support of American industrialists, scientists, social workers, and middle- and upper-class Puerto Ricans influenced by neo-Malthusian arguments supporting widespread birth control, public health officials decided to put into effect a plan to control the birth rate on the island. This policy, though seemingly based on scientific principles, was based on a set of stereotypes about Puerto Ricans that characterized them as racially inferior and unable to make their own decisions about their fertility. It is in this way that the insular government developed public policy to control what they labeled as a “culture of poverty.” In this regard, the fate of the Puerto Rican women was in the hands of American scientists and demographers and local government officials. By distinguishing between superior and inferior persons in their policy of population control, these officials implemented policies based on eugenic assumptions that served the needs of U.S. business interests by disciplining the reproductive habits of their workforce.

Americans’ views about the connection between Puerto Rican racial inferiority and what they saw as an out-of-control birth rate reinforced the assumptions that justified the Americans’ presence on the island. One might agree with Nancy Stepan’s book The Hour of Eugenics, in which she observes that, for an imperial power like the United States, “Eugenics, was more than a set of national programs embedded in national debates; it was also part of international relations.” Thus, the attempt to discipline the reproductive habits of Puerto Rican women was not unusual, since they were colonial subjects and the population policy was part of the colonial experiment.

Operation Bootstrap

In 1948, Puerto Rico elected its first governor. Luis Muñoz Marín had campaigned for economic reforms and structural changes in the political relationship between the Unied States and islanders. Muñoz and other political leaders considered agricultural countries to be underdeveloped and industrial countries developed; manufacturing was seen as the means by which Puerto Rico could develop economically.

As a result, the government launched an industrialization program known as “Operation Bootstrap,” which focused primary on inviting American companies to invest on the island. These companies would receive incentives, such as tax exemptions and infrastructural assistance, in return for providing jobs for the local population. Under “Operation Bootstrap,” the island was to become industrialized by providing labor locally, inviting investment of external capital, importing the raw materials, and exporting the finished products to the United States market.

Due to the nature of the American companies that participated in the plan, women were recruited to work these new jobs, such as those in the garment industry. In these jobs, women often functioned as the main or co-provider in their households and continued to confound the myth of the male breadwinner. Additionally, women continued to participate in the labor movement, protesting for equal wages and better treatment.

During “Operation Bootstrap,” the question of the Puerto Rican birthrate remained a public policy issue. Governor Muñoz feared that the plan for industrial modernization might be in jeopardy if he did not take steps to deal with the “overpopulation” problem. Thus, the administration set about educating the population about birth control, and encouraging surgical sterilization. In other instances, the local government fostered the migration of Puerto Ricans to the U.S. mainland and overseas possessions such as Hawaii. These measures were highly criticized by civil rights groups and the Catholic Church, who perceived this campaign as an unwarranted attempt to restrict individuals’ reproductive rights. In addition, candidates who were challenging the sitting government denounced the discriminatory nature of these public policies.

Governor Muñoz Marin and his cabinet were concerned about the possible electoral repercussions of coercive sterilization policies. Luis A. Ferré, who was Muñoz’s political opponent, alleged that some women were being hired on the condition that they undergo surgical sterilization. Ferré maintained that his allegations were informed by women from one of the factories in the town of Cayey. Muñoz’s advisors suggested that discrimination against women in the work environment on the grounds that they were not sterilized would be a political blow to the Governor’s reelection efforts. As a result, Muñoz ordered a complete investigation, after which he was forced to intervene and reevaluate the role of the government in birth control policies.

Conclusion

Official documents, census data, newspaper articles, and photographs from this time period in Puerto Rico’s history shed light on the complicated roles women have played in Puerto Rican society. American companies and government officials recognized that working women were necessary for increased industrialization. Women’s participation in these new industries opened up the opportunity for them to become household breadwinners and participate in the labor movement alongside men. This participation in industry and in the labor movement, however, also brought with it a slew of government regulations about women’s health, primarily birth control and forced sterilization, often based on eugenic assumptions about the racial inferiority of Puerto Rican women. Thus, it is important to continue to reflect upon the profound ways in which gender influenced the relationship between these workers and the economic system.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

The censuses, newspaper and magazine articles, official documents, and photographs in this module all shed light on the changing roles of women workers in Puerto Rican society in the period after the United States took control of the island. Taken together, since they are presented in roughly chronological order, they can be used to reflect upon the ways in which gender influenced the relationship between these workers and the global economic system over 60 years of Puerto Rican history.

First, it’s important to highlight the proximity of Puerto Rico to the United States. Understanding this geographical closeness will enable students not only to visualize Mrs. Roosevelt’s trip but also to understand why Mrs. Roosevelt’s article is entitled “Our Island Possession.” Mrs. Roosevelt’s narrative highlights the islanders’ customs, the climate, and the role of women in the working environment. In addition, the article sheds lights on Mrs. Roosevelt’s concern for her fellow humans.

The two census documents included in the packet (1920-1940 and 1940) provide a profile of the island’s employed population. They show the differences between men’s and women’s employment opportunities, and women's employment over time. Particular emphasis should be made to the decade of the 1930s, the impact of the Great Depression in the world economy, and the increased industrialization and U.S. control that it enabled in Puerto Rico.

The article from a union newspaper gives an understanding of topics and issues published in the period. It is important to note the language associated with the socialist movement that the workers adopted. This discussion could fit into a more general discussion of the labor and socialist movement around the world and in the United States.

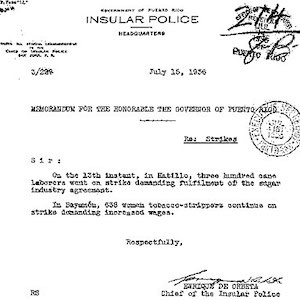

The official documents included in this packet serve to document the active role of women in the labor movement. The telegram from the Strike Committee and the letter from the Chief of Police to the Governor record the attitude of the police towards workers’ strikes. These documents also demonstrate that while industrialization was taking place in Puerto Rico, some women were subject to discrimination. Excerpts taken from minutes of a Governor meeting with his cabinet provide an excellent example of how the issue of sterilization could determine the course of a political campaign.

Discussion Questions

- How did the new economic order affect women and in what ways did they manage to integrate into it?

- What kind of jobs were women working from the 1930 to the 1950s?

- As important members of the working class, what were the challenges that women confronted during the period of industrialization?

- How did the labor movement give “voice” to the working class women?

Lesson Plan

Puerto Rican Women’s Labor Movement

Time Estimate

Three 45-minute class periods and one additional day for writing the DBQ.

Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to:

- learn the steps involved in crafting an essay using primary sources.

- identify point of view in a variety of sources.

- identify other points of view or types of sources not represented in the sampling.

- interpret and evaluate the role of women in the Puerto Rican workforce as seen in multiple sources, and from multiple perspectives.

- identify factors that create different perspectives for women from different countries.

- discuss the participation of Puerto Rican women in the global economy.

- work in small groups to discuss different perspectives and points of view. cooperate with a group in order to formulate an answer to a question.

- write a five-paragraph essay comparing Roosevelt’s depiction of Puerto Rico with that found in contemporaneous source documents.

Materials

- Copies of the following for each student:

- Puerto Rican Labor Movement Introduction

- Enlarged Photograph of Source 10: Photograph, Striking Workers

- Source 5: Magazine, Eleanor Roosevelt

- Source 2: Quantitative Evidence, 1940 Census

- Source 7: Newspaper, Needleworker Strike

- Source 8: Official Document, Women's Union Telegram

- Source 9: Official Document, Police Letter

- Source 6: Official Document, Women's Employment

- Source 4: Photograph, Worker’s Celebration

- Source 11: Photograph, Tobacco Workers

- Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Images

- Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts

- Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Quantitative Evidence

- Key Questions for the essay

- Optional:

- Classroom computer, projector and screen

- This lesson can also be done in the school computer lab. Students can read online, download and complete worksheets, and email them to the instructor. Printing could be optional.

Strategies

-

Homework: Before the first lesson, have students read the Puerto Rican Labor Movement Introduction

-

Hook: Pass out one copy of the Enlarged Photograph of Source 10: Photograph, Striking Workers and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Images to each student.

Introduce the discussion of Puerto Rican women in the labor force using the photograph and accompanying text. If possible, project the image of the photograph onto a large screen. Ask what impressions the photograph gives of women strikers.

Next, examine the photograph with the students, following the image worksheet. Have students fill in answers as you go over the worksheet. Ask students to isolate aspects of the image; if possible, crop them on the screen so all can see.

Finally, analyze elements of the photograph to introduce the prominent themes of the lesson. Discussion of violence (police), gendered labor (crops), imperialism and globalization (flags), and gender roles (gender) will be woven throughout the lesson.

- Police:

- Find the guards or policemen. Ask how are they distinguishable.

- Ask what they appear to be doing, and whether the situation looks violent.

- Ask whether it appears that violence was used against women strikers.

- Crops:

- Find the crops, and guess what kind they are.

- Guess if this work was performed by both men and women.

- Flags:

- Look at the flags. Try to identify them and determine what they symbolize in that setting.

- Ask why people would bring flags to a strike.

- Ask if the use of the U.S. flag in Puerto Rico represents imperialism.

- Gender:

- Do the people in the photograph appear to be mostly men, women, or even?

- How does that affect your understanding of women participating in strikes?

- How would it be different if it were all men?

- What does this indicate about women in the labor force?

Ask students whether this photographic source provides rich information, and if so, what.

Ask if students have any questions before turning in their worksheets. Students turn in their worksheet before the end of class. -

Homework: Give students copies of Source 5: Magazine, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts. Students will complete the worksheet, based on the Eleanor Roosevelt article, and bring to the next class.

-

Review Source 5: Magazine, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts. Return homework to students. Point out strengths and weaknesses of their responses. Ask for questions. Ask students what they learned about Puerto Rican women in the labor force. Ask students to offer responses for individual questions on the worksheet.

-

Read this quote from Eleanor Roosevelt, referring to women needleworkers, “A few of them who work in factories earn fair wages, but for sewing done at home they are paid absurdly low pages.”

Questions for the class:

- What is Roosevelt’s attitude toward Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican women workers?

- What economic suggestions does Roosevelt make for Puerto Rican women workers?

- How would those changes affect the gendering of labor in Puerto Rico?

- Does it appear that Mrs. Roosevelt is aware of women participating in labor strikes?

- Group Analysis of Primary Documents: The final goal of this lesson is for students to be able to put together an essay using primary sources to support their arguments. This is the scenario they will use for their essay:

- What differences do you see in the work done by women and by men?

- How do needleworkers in the census report compare to needleworkers described in Roosevelt’s article?

- How does this compare to Roosevelt’s claim that women needeleworkers in factories receive “fair" wages”?

- What are the benefits for women to join unions?

- What does this telegram say about women’s beliefs about their rights?

- Why do you think these women are seeking help from the Governor, who is appointed by the United States, rather than another Puerto Rican official?

- How does this letter to the Governor compare to Roosevelt’s portrayal of Puerto Rico?

- How does this letter indicate that women are a significant part of the labor movement?

- What does this report cite as the major changes in the needleworking industry over the previous 18 years?

- What does this report say about the value of needleworkers in society?

- What does this photograph show about the beginning of labor unions in Puerto Rico?

- Why do you think the written part of the banner is in English and says “Labor Day”?

- Does this photograph show the improvement that Roosevelt sought?

- What does this photograph document about the division of labor?

-

Essay: Assess learning with five-paragraph essay as homework.

Instructions: Imagine you are a Puerto Rican woman political activist organizing unions at the same time that Eleanor Roosevelt writes her article. Draft a response to Roosevelt’s call for manufacturing and improvement of the island that will be published in the same U.S. journal, Woman’s Home Companion.

Use the Key Questions to help guide your essay writing. You must use at least two of the primary sources from this lesson. Your essay should either:

- Analyze Eleanor Roosevelt’s position using documents; or

- Compare and contrast Eleanor Roosevelt’s position with your own (remember, you are a Puerto Rican woman activist)

Imagine you are a Puerto Rican woman political activist organizing unions at the same time that Eleanor Roosevelt writes her article. Draft a response to Roosevelt’s call for manufacturing and improvement of the island that will be published in the same U.S. journal, Woman’s Home Companion.

The intermediate objective is for students to present their findings and take notes on other groups' findings, so that each student has a body of points to draw on for his or her final essay.

Part One: Working together in small groups, students will read and discuss issues as they each complete a worksheet to understand their group's primary source.

Part Two: With the information that they gain from analyzing primary sources, each group of students will make a list of four points to be used in writing a response to Mrs. Roosevelt. Each point will be supported with a quote from or an interpretation of a primary source. As a group, students will present their analysis of their four strongest points to the class, describing how they came to their decisions.

Assign each group one of the following primary sources. Ideally each source will be examined by at least one group. It is fine if more than one group examines the same source. Starting questions are provided below each of the listed primary sources.

Source 2: Quantitative Evidence, 1940 Census and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Quantitative Evidence

Source 7: Newspaper, Needleworker Strike and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts

Source 8: Official Document, Women's Union Telegram and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts

Source 9: Official Documents, Police Letter and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts

Source 6: Official Document, Women's Employment

Source 4: Photograph, Worker’s Celebration and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Images

Source 11: Photograph, Tobacco Workers and the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Images

Differentiation

Advanced Students: These students should be encouraged to search for information on Luisa Capetillo, a Puerto Rican labor organizer, who lived from 1879-1922. Start with Wikipedia, and see how much information you can dig up. Look for primary sources; see if you can find any publications by her. With this information, try writing your essay again, only this time using the words of Luisa Capetillo in contrast to Eleanor Roosevelt’s. How does information about Capetillo change your perception of Puerto Rican women activists? For what act was she most famous?

Visual Learners/Less Advanced Students: These students could draw or design their own flag for the Puerto Rican women’s needleworker union. Try to make it fit the style of the 1930s. Look at the Spanish Civil War module for examples of “Poster, Farm Women” and “Poster, Factory Woman” in the 1930s. How might the Puerto Rican designs be different? Try to design a poster that fits with our readings. You can use elements of the primary-source photographs. What symbols should the flag incorporate? How will people recognize it? What does it symbolize?

Another option would be to skip the culminating essay and end with the document comparisons.

Document Based Question

Document Based Question (Suggested writing time: 40 minutes)

Directions: The following question is based on the documents included in this module. This question is designed to test your ability to work with and understand historical documents. Write an essay that:

- Has a relevant thesis and supports that thesis with evidence from the documents.

- Uses all or all but one of the documents.

- Analyzes the documents by grouping them in as many appropriate ways as possible. Does not simply summarize the documents individually.

- Takes into account both the sources of the documents and the authors' points of view.

You may refer to relevant historical information not mentioned in the documents.

Question: Drawing on specific examples from the official document on women's employment and other sources in the module, discuss ways in which the United States demonstrated interest in Puerto Rican women needleworkers, and how the workers responded. Analyze how the experience of Puerto Rican women workers fits into the theme of women entering the global workforce.

Be sure to analyze point of view in at least three documents or images.

What additional sources, types of documents, or information would you need to have a more complete view of this topic?

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Milagros Denis teaches at Rutgers University in New Jeresy. She received her doctorate from Howard University, and her dissertation is entitled “One Drop of Blood: Racial Formation and Meanings in Puerto Rican Society, 1898-1960.” She has received fellowships and assistantships allowing her to pursue her research interests in Latin American and Caribbean history.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Rachel Pooley did her undergraduate work at the University of Michigan, and earned her MA in Latin American Studies at the University of Texas at Austin. She has experience teaching in a bilingual elementary school, and currently is working on a Masters of Science in Information at the University of Michigan.

This teaching module was originally developed for the Women in World History project.