Long Teaching Module: Western Views of Chinese Women

Overview

As the sources in this module illustrate, this fundamental distinction between the Western and the Chinese was expressed in both implicit and explicit ways in the foreign press. Chinese women became representative objects for Western observers, proof of the failings of Chinese culture and the necessity of Christian conversion. Described as victims of their own society, in these pieces Chinese women were in fact victims of a foreign pen, deprived of any agency in their own existence and judged with a sympathy born of arrogance. The representations of Chinese women in these journalistic accounts bear uncanny similarities to popular conceptions about the “place” of women in Confucian societies today—primarily that they are passive, obedient, and oppressed. A guided critical analysis of samples from 19th-century Western writing about Chinese women is one means of confronting popular stereotypes about Chinese/Asian women that abound in Western culture. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

Essay

Women in China

Generally speaking, women in 19th-century China followed gender norms classed by Western scholars as Confucian or Neo-Confucian. These norms emphasized the family as the primary social unit and advocated the primacy of women in the domestic sphere. Within the Chinese family, one’s position in the hierarchy determined rank and responsibility. Daughters were expected to obey their parents’ authority, assist their mothers in domestic tasks, and, in elite families, learn to read and write.

When the time came, young women would marry into a family of their parents’ choosing, leaving the home of their birth permanently. Once married, young wives would enjoy a position relative to their husband’s place in the family. The wife was always subject to her mother-in-law’s authority in addition to her husband’s. She took management of the household when those duties were ceded by her mother-in-law, ensuring that its members were well cared for and that its finances remained in order.

The birth of a son would be a happy occasion for the entire household, as it would guarantee not only the continuity of the family line, but also insurance for both parents that they would be provided for in their old age and worshipped after their death. The mother would have the added comfort of knowing that her own subservient position in the household would be reversed when her son married.

Whereas elite standards of gender were promoted as the ideal throughout Chinese society, in reality “feminine” behavior was shaped by economic class and social status. Among elite families, proper young women were sequestered in the “inner quarters,” their chief company the other women of the household. Their self-imposed cloister within the domestic sphere was considered a marker of propriety and restraint, qualities promoted for both men and women in neo-Confucian culture. However, this “restraint” was only possible for women who had servants to facilitate their seclusion. By contrast, rural women who lived in farming communities regularly left their homes to tend fields or visit the market, their economic situation making the division of their household into inner and outer (private and public) realms near impossible.

Concubines and Bound Feet

Western observers often remarked on two customs prevalent in 19th-century China: concubinage and foot binding. Although taking a concubine was supposed to be a method of last resort for a patriarch to acquire a male heir, the practice was long established as a marker of elite status. Western writers improperly termed this practice “polygamy,” or taking multiple wives. In fact, the position of the wife remained sacrosanct with regards to her authority in the household and her role as “mother” to all of her husband’s progeny. A concubine was not a wife.

Foot binding is best understood as a form of beauty culture that became increasingly popular in China during the late imperial period, reaching its height during the 19th century. Thought to have originated in the late Tang dynasty (618-907 CE), foot binding was first adopted by elite women. By the 19th century, the practice transcended class, although families of lesser means would bind their daughters’ feet at a later age than occurred in elite families due to the need for their daughters’ labor. During the Qing dynasty (1644-1911 CE), foot binding became a marker of Han Chinese ethnicity, as neither the ruling Manchus nor other differentiated minority populations (such as the Hakkas) promoted the practice.

Protestant Missionaries in China

The first Christian missionaries in China were the Jesuits, who arrived at the Ming court in the 16th century. Their activities were strictly proscribed in the 18th century, however, and Catholic priests were forbidden to make converts among the Chinese people.

Protestant missionaries arrived at China’s southern coast in the beginning of the 19th century. Their activities were limited to Macao and Canton due to Chinese restrictions on foreigners. This situation changed following the Opium War (1839-1842), when five “treaty ports” along China’s southeast coast were opened to foreign residence and trade.

Another significant development occurred in 1858, when foreign missionaries won the right to travel inland and establish Christian communities in the Chinese countryside. From this time forward, female missionaries who were able to directly preach to Chinese women arrived in China in increasing numbers.

Representations of Chinese Women

There is very little in these sources that provides substantive information about how Chinese women lived in the 19th century. Instead, in reading these pieces, we learn about the prejudices and mindsets of their authors. In every primary source in this module, the audience is “us” (the West) and the subject is “them” (the Chinese). This distinction between self and other is also marked in the text: the observer/author is the active agent (he or she describes) and the Chinese woman is the passive object (she is described). In many of the articles, this passivity is made real: Chinese women are presented as victims without recourse, their only hope the renovation of their own society. In some cases, however, Chinese women are endowed with the “universal” female attribute of moral authority; this development marks a shift in representation whereby Chinese women are transformed from victims in need of rescue to ignorant souls in need of enlightenment.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

Strategies

There are three main trends in the primary sources that may be useful to focus on in a classroom discussion:

- Making distinctions

- Issues of authority

- Gender and representation

Although each of these trends may be found in any given source, the packet was organized to facilitate discussion of specific trends within a discrete group of documents. Thus, the first three sources (Remarks on Chinese Character and Customs; The Seven Deadly Sins of Confucianism; The Ethics of Christianity and Confucianism Compared) were chosen because they highlighted the distinction between Confucianism and Christianity. Students should consider the manner in which Chinese women are located in this discussion. In each piece, it is these women’s perceived hardships that are presented as proof of the degeneracy of Confucian civilization. This “proof,” in turn, implicitly points to the superiority of Christian/Western civilization.

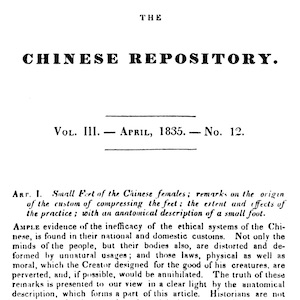

The sources that relate to the practice of foot binding (The Small Feet of Chinese Females, 1835; The Small Feet of Chinese Women, 1869; Small Feet: Two Opinions; Bound Feet: An Alternate View) are quite interesting in their own right. They also nicely demonstrate the rhetorical strategies used to assert Western authority on the subject of Chinese culture. The first three of these pieces utilize scientific language to defend a moral judgment on a cultural practice. Students with a background in natural or social science will quickly realize that there is very little that is “scientific” about these observations. These documents also show the insularity of the Western observer: these authors most often cite other Western observers (or, in the case of the letter writers, each other) in forming their arguments about foot binding. Ultimately, the discussion is guided by the authors’ prejudices rather than “facts” about the practice. The photograph provides a contrasting view of bound feet by placing “small feet” in their proper cultural context—as a form of adornment.

The final three pieces (Schools for the Education of Chinese Girls, Women’s Work for Woman, Domestic Life of Woman) are authored by women. Students will note that the tone of these articles differs markedly from those authored by men. Chinese women are presented as agents rather than victims. In each of these articles, women are either explicitly or implicitly acknowledged as enjoying authority within the domestic sphere. In Women’s Work for Woman, it is even possible to read resistance on the part of adult women in that they are portrayed as less willing to convert. Nevertheless, there is also a consistent effort made to distance Chinese women from Western women. In each case, the reader is made to understand that the Western woman enjoys a superior position relative to her Chinese counterparts.

Discussion Questions:

- In these pieces, how do the authors distance themselves from their Chinese subjects? How does the implicit distinction between the West and China affect the way in which Chinese women are presented to the Western public?

- In exploring this question, students should look to the language and style of the articles in this packet. Often, an aside or a qualified comment stands as a marker that links the author and the reader together and excludes the Chinese subject. References to “us” or “we” proliferate, for example. The Chinese subject becomes “the other,” laden with descriptors that distinguish “us” (active, scientific, moral) from “them” (passive, superstitious, depraved).

- What distinctions may be made between female and male authorship in these pieces? Can these articles teach us something about their female authors?

Students may wish to compare the representation of Chinese women in the first group (Remarks on Chinese Character and Customs, The Seven Deadly Sins of Confucianism, The Ethics of Christianity and Confucianism Compared) to the third group (Schools for the Education of Chinese Girls, Women’s Work for Woman, Domestic Life of Woman). Generally speaking, women in the first group of documents are presented as passive victims of Confucian culture. In the latter group, women are presented as either active participants in their own culture or as possessing the potential to influence those around them.

Students should be encouraged to consider the conditions of male versus female authorship. For example, male missionaries sought to convert patriarchs who would bring their families into the church with them. Female missionaries worked with women and therefore needed to present their subjects as both worthy of conversion (i.e. possessing the mental aptitude to convert) and as influential within the larger family.

Students should also be encouraged to grapple with the question of why Western women employed the same techniques as their male counterparts in distancing Chinese women from themselves. Rather than lamenting women’s common lot in patriarchal societies, Western women represent themselves as being better off than Chinese women—in many cases implying that the Western gender order represents the universal ideal. Students can also compare the views of Western women with the those expressed by Chinese women like Qiu Jin whose poem references footbinding.

Lesson Plan

Western Missionary Views of Chinese Women: A Roundtable Discussion

Time Estimate: Three 47-minute class periods.

Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to:

- analyze point of view in primary source documents

- determine the effect of gender on point of view

- participate in a roundtable discussion on Western views of the status and role of Chinese women in their society

- reflect on how their discussion may reflect the point of view of 21st century Americans

Materials

- A printed packet of all of the sources listed below should be made for each student, so that s/he can mark directly on the copies to analyze point of view. Of course, students also could be directed to use the versions online with editing programs (like Microsoft Word) instead.

- Source 1: Missionary Journal, "Chinese Character"

Lay, G. Tradescant. “Remarks on Chinese Character and Customs.” Chinese Repository 12 (1843): 139-142. - Source 2: Newspaper, Confucian Women

North China Herald and Supreme Court and Consular Gazette, “The Natural History of a Chinese Girl,” July 18, 1890. - Source 3: Missionary Journal, Christianity and Confucianism

“The Ethics of Christianity and Confucianism Compared.” Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal 17 (1886): 377-378. - Source 4: Missionary Journal, Foot Binding 1

“Small feet of the Chinese females: remarks on the origin of the custom of compressing the feet; the extent and effects of the practice; with an anatomical description of a small foot.” Chinese Repository 3 (1835): 537-539. - Source 5: Missionary Journal, Foot Binding 2

Dudgeon, J., M.D. “The Small Feet of Chinese Women.” Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal 2 (1869): 93-96. - Source 6: Missionary Journal, Foot Binding 3

Kerr, J. G., M.D. “Small Feet.” Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal 2 (1869): 169-170; G., H. “Correspondence: Small Feet.” Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal 2 (1870): 230-232. - Source 7: Photograph, Foot Binding

Photograph of Northern Chinese woman, late Qing period. In Every Step a Lotus: Shoes for Bound Feet, Dorothy Ko. Berkeley: University of California Press; The Bata Shoe Museum Foundation, 2001. - Source 8: Missionary Journal, Chinese Education 1

“Schools for the Education of Chinese Girls.” Chinese Repository 3 (1834): 42-43. - Source 9: Missionary Journal, Chinese Education 2

Farnham, J.M.W. “Women’s Work for Woman.” Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal 16 (1885): 218-219. - Source 10: Missionary Journal, Chinese Culture

“Domestic Life of Woman.” Chinese Recorder and Missionary Journal 17 (1886): 153-154. - Source 11: Poem by Qiu Jin, Chinese feminist.

- Sufficient copies of Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts

Download Primary Source Packet

Download Text Analysis Worksheet

Strategies

Day 1:

1. Hook: The teacher will introduce the lesson by showing students images of different kinds of fashions for women that restricted or inhibited their movement such as corsets, high heel shoes, mini-skirts, heavy jewelry, and Chinese foot binding. To show Chinese foot binding, the teacher could use Source 7: Photograph, Foot Binding, which depicts a Northern Chinese woman with bound feet from the late Qing period. The teacher will start a discussion by asking the following questions:

- How do these fashions restrict or inhibit movement?

- Why would women willingly choose these fashions?

- What kind of people might criticize these fashions?

2. Objectives: The teacher will then explain the objectives of the unit and how the students will be working toward a roundtable discussion on Western views of the status and role of Chinese women in 19th-century China. The teacher also will show the students the Document-Based Question on the topic.

3. Modeling: The teacher will demonstrate how to use the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts for one of the sources. The teacher also should explain how to identify point of view in the sources by highlighting or underlining parts of the documents that reveal the author’s opinion on the status and role of Chinese women in their society. Point of view comes from the author’s gender, occupation, culture, religious affiliation, purpose for writing the document, audience for the text, and social class. Furthermore, point of view can be determined from the text itself.

The teacher can alert the students to look for key phrases that indicate tone and therefore the author’s attitude toward Chinese women’s status and roles in Chinese society. The teacher should model how to find tone by pointing out the positive and negative words used in the sources. For example, in Source 1: Missionary Journal, "Chinese Character", “Remarks on Chinese Character and Customs,” the author labels Confucianism a “diabolical system of ethics,” and in Source 8: Missionary Journal, Chinese Education 1, “Schools for the Education of Chinese Girls,” the author observes that in China women are “generally and greatly despised,” but that “it has been pleasing to witness for some years the gradual decline of prejudice against female education.”

4.Homework: The teacher will distribute the primary sources as a packet for the students to analyze for homework (and show them how to access the documents online if they prefer to read and mark on electronic versions). The students will use the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts to identify the authors’ points of view on the status and role of Chinese women in their society, i.e. what opinion do they have about Chinese women and how does their gender, occupation, culture, religious affiliation, audience, social class, and purpose inform their point of view on Chinese women’s status and role in Chinese society.

Day 2:

5. Roundtable Discussion Preparation: The teacher will assign students to the following roles for a roundtable discussion on Western views of the status and role of Chinese women in 19th-century China. The numbers in parentheses indicates the maximum number of students to be assigned to that role in the roundtable. If the class size exceeds 28, then the teacher can assign moderators to keep the discussion going. The teacher also could assign a student to give a brief introduction to the roundtable and one to summarize the major arguments at the end. Another role could be to lead a reflection on the extent to which their current views about women’s status and roles in American society affected their presentation of their role in the roundtable. If the class is small, the teacher should fulfill those duties.

Roundtable Speaking Roles:

- Missionary men (3)

- Missionary women (3)

- Male readers of the missionary journals in the United States or Great Britain (2)

- Female readers of the missionary journals in the United States or Great Britain (2)

- Chinese Confucian men with wives whose feet are bound (2)

- Chinese Christian men with wives whose feet were not bound (2)

- Chinese Christian women without bound feet (2)

- Chinese women with bound feet (2)

- Chinese peasant women without bound feet (2)

- Qing Dynasty government official posted in Shanghai (2)

- Qing Dynasty government official posted in the Forbidden City (2)

The students will work on preparing their arguments for a roundtable discussion. They must show the teacher the three statements they plan to make during the discussion and the source(s) they used to prepare their statements. The teacher should encourage the students to anticipate arguments from the other side, and to confer with their classmates who have the same views to make sure that their statements are not too repetitive.

Day 3:

6. Roundtable Discussion: Students will conduct the roundtable discussion on the status and role of Chinese women in their society. If possible, the chairs in the classroom should be organized in a circle.

7. Wrap-up: Students will discuss how much their current views on women’s roles affected their statements on behalf of 19th century people.

8. Homework: Students will write the DBQ.

Differentiation

Advanced Students: After the roundtable, advanced students should be able to have a more sustained discussion of the problems of presentism when looking at controversial issues in the past, such as foot binding of Chinese women. The teacher could direct their attention back to their comments about current fashions that restrict women’s movements to compare their attitudes toward fashion today and the norm of foot binding in 19th-century China among the elite of the Chinese social classes.

Less Advanced Students: For students needing additional introduction to analyzing primary sources, the teacher should model the analysis of one source in detail, using the same analysis sheet that the students will use for homework, the Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts. I recommend using the Source 2: Newspaper, Confucian Women, “Natural History of a Chinese Girl,” to help students see the Western attacks on the negative effects of the Confucian system on women. Students will be able to follow the teacher’s analysis in the list of “Seven Deadly Sins of Confucianism.”

Additionally, the teacher should sustain a discussion with the students on how the missionary background of most of the authors and their audiences would make them use negative adjectives about Confucianism and positive adjectives about Christianity. The teacher also should give the students some information about Victorian sensibilities in 19th-century Great Britain and the United States that elevated middle class women to a “separate sphere” where they held the responsibility for moral education of their children and moral standards for their husbands.

Document Based Question

(Suggested writing time: 40 minutes)

Directions: The following question is based on the documents included in this module. This question is designed to test your ability to work with and understand historical documents. Write an essay that:

- Has a relevant thesis and supports that thesis with evidence from the documents.

- Uses all or all but one of the documents.

- Analyzes the documents by grouping them in as many appropriate ways as possible. Does not simply summarize the documents individually.

- Takes into account both the sources of the documents and the authors' points of view.

- You may refer to relevant historical information not mentioned in the documents.

Question: Using the sources provided, compare and contrast different 19th-century Western attitudes toward Chinese women’s status and roles in Chinese society.

What additional sources, types of documents, or information would you need to compare and contrast more completely 19th-century Western attitudes toward Chinese women’s status and roles in Chinese society?

Bibliography

Credits

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following institutions for primary sources: Dr. Chisheng KO

About the Author

Cecily McCaffrey is Associate Professor of History at Willamette University. Cecily McCaffrey teaches courses in Asian History, with a primary focus on the modern period. Her courses include a four semester sequence in Chinese history, ranging from the medieval era to the present day, as well as specialized courses in environmental history, war and memory, and popular resistance movements. Her classes emphasize skill-building in close reading, critical analysis, and historical writing.

Her current research centers on the White Lotus Uprising of the late 18th century, a religiously-inspired revolt against imperial authority that endured for a decade in central China. She is particularly interested in capturing the experiences of the people who were caught up in the movement in its different stages, whether die-hard rebels or those forcibly conscripted. Her work considers the uprising in two ways: first, as an episode of resistance to state authority; second, as a mirror of environmental, political, and social conditions at the time.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Sharon Cohen teaches world history in suburban Maryland. She served on the AP World History Development Committee from 2002 to 2015, wrote the Teacher’s Guide for AP World History and edited Special Focus on Teaching About Latin America and Africa in the Twentieth Century (2008). She helped found the online journal World History Connected and received the 2015 Pioneer in World History from the World History Association.

This teaching module was originally developed for the Women in World History project.