Long Teaching Module: Parents, Children, and Political Authority in 19th century Argentina

Overview

Between 1810 and 1860, Argentina emerged as a deeply divided nation. One of the main problems that remained unresolved throughout the 19th century was how power would be shared between Buenos Aires, the capital, and the rest of the provinces. Juan Manuel de Rosas, who ruled the country between 1829 and 1852, provided some semblance of order. However, he failed to share power with other groups, and the nation was not able to establish a lasting peace until the early 1860s. Studying this period is significant because it allows us to better understand the reasons for underdevelopment, authoritarianism, and political instability in Argentina's not so distant past and why these problems continue to exist in many parts of Latin America today. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, potential adaptations, and essay prompts relating to the eleven primary sources.

Essay

A New and Divided Nation

After Argentina formally declared its independence from Spain in 1816, partisan wars broke out between two elite factions, Federalists and Unitarians. These groups had vastly different visions for how Argentina should be governed, but these views were based mostly on self-interest rather than ideology. Unitarians promoted the idea of centralizing power into Buenos Aires. They sought to reduce the power of the Catholic Church, which they saw as a symbol of the "colonial past." and they wanted to establish freer domestic and foreign trade. Unitarians also imagined a nation that promoted European-style "progress" and "civilization." This vision of modernization favored European immigrants over Argentina's poorer gaucho (rural itinerant workers) population and caudillos (regional strongmen). During the 1820s, Unitarian governments in control of Buenos Aires attempted to implement their reforms throughout the nation.

Opposing these efforts, Federalists emerged as a broad-based group, including ranchers and local merchants, who saw free trade and foreign competition as threats to their economic interests. Federalists tended to favor local political control and viewed Unitarians' political reforms as violations of their sovereignty. Federalists also wanted to maintain the power of the Church as an institution of social control. The Unitarians rejected what they called the "barbarism" of Federalist supporters, including Argentina's poorer gaucho (rural itinerant workers) population and their caudillo (regional strongman) leaders.

Throughout the 1820s, Unitarian governments implemented their reforms in Buenos Aires while the rest of the country fiercely resisted these efforts. Political tensions mounted when, in 1826, Unitarians tried to impose a Unitarian constitution over the rest of the country. However, in the following year, the Unitarian government in Buenos Aires resigned under pressure from powerful interests within the interior provinces. Manuel Dorrego, a Federalist, became governor. One of his first acts was to invalidate the Unitarian constitution, but he especially angered Unitarians by establishing peace with Brazil, which had been at war with Argentina since 1825. Both countries had been fighting for control of the eastern bank of the River Plate. Unitarians wanted to continue the war in order to add another province to Argentina and to prevent the loss of lands held by wealthy ranchers from Buenos Aires. However, the war was costly, and in late 1828, Dorrego accepted a British-brokered deal, which recognized the creation of a new "Uruguay" as a buffer state between the two countries. Returning from their military campaigns, Unitarian forces overthrew the Federalist government and assassinated Dorrego. The provinces did not accept the Unitarian constitution, and civil war broke out.

"The Restorer of the Laws"

In response to the discord, different regions of the country experienced the rise of brutally repressive regimes ruled by caudillos, who re-established order. Beginning in 1829, Juan Manuel de Rosas, a wealthy rancher and Federalist, asserted his control over Buenos Aires and the rest of the nation. Supported by a powerful, large land-holding class, Rosas governed through a combination of patronage and state violence. Seen by his supporters as "The Restorer of the Laws," he sanctioned property confiscation, execution, torture, and forced exile against Unitarian suspects and other political enemies.

Historians often underscore Rosas's brutality against his foes by pointing to the headings on most official documents: "Long Live the Federation! Death to the Savage Unitarians!" By 1835, Rosas dominated the other provinces, expanded the Indian frontier, awarded land to influential people and loyalists, and exported wool and hides to meet the demands of Western Europe. In 1852, the dictator's reign ended when other Federalists, tired of his meddling in provincial affairs, defeated him at the Battle of Caseros.

Youth and the Rosas State

The political violence, civil strife, and authoritarianism of the early 19th century deeply affected the daily lives of young people. One consequence was the weakening of powers that fathers, as patriarchs, had within the household. Colonial authorities long recognized the traditional legal concept of patria potestad, whereby absolute authority within families was given to male heads. This meant that patriarchs would have, in theory at least, the last word over their children's life decisions, particularly relating to education, work, and marriage. After independence, however, patriarchal authority began a slow decline. Hundreds of male heads of families were imprisoned, killed, drafted into Unitarian or Federalist armies, or took extended leaves for business or seasonal labor.

For middle class and elite families, Argentina's political leaders viewed schools as one of the most important institutions of civil life and social control. The idea was that teachers would aid in the state's efforts to incorporate children into the political system. Indeed, scholars have shown that primary and secondary schools were crucial in educating an entire generation of new Argentine citizens. Thousands of boys and girls were not only taught grammar and arithmetic, but also a deep respect for authority and patriotic values.

The Rosas state moved aggressively to employ lower-class youngsters when the wars and civil strife of the early 19th century caused labor shortages, especially in rural areas. Social critics also saw lower-class children as a potential source of social disorder and sought to harness their energies as laborers. Law enforcement officials restricted youngsters' mobility by strictly enforcing passport and anti-vagrancy laws.

In towns across Argentina, the conchabo system gave local police broad authority to draft children to work in public works projects, private homes, factories, or wherever laborers were needed. The office typically in charge of placing young workers was called the defensor de menores, a public institution dating back to the colonial period. The defensor drew up labor agreements that tied young people to particular jobs, but these contracts had the unintended effect of giving young people some degree of freedom from parental authority.

Argentina's laws also allowed children to be entrusted with decisions related to marriage and property. Girls could marry and hold a dowry at the age of 12. Boys could not marry until they turned 14. This is not to say that parents or their children sought marriage contracts at these early ages. By law, girls and boys had to wait until they were 23 and 25 years old, respectively, before they could marry without permission from their parents. After 1810, however, young people were marrying at younger ages and had more input into selecting spouses. This included choosing mates who were closer to their own ages and sometimes outside their familial socio-economic and racial boundaries.

Parents lamented with growing frequency and alarm the rebelliousness of their children and attempted to control their behavior through legal means. Many of these disputes appeared in lawsuits, or disensos, filed by parents asserting their parental rights and obligations in order to guide the behaviors of their children. Sons and daughters also sued their parents, seeking the right to marry freely partners of their own choosing.

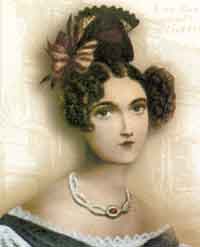

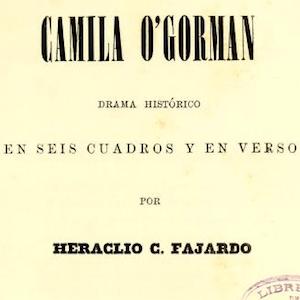

While these individual actions played out in the courts, authorities under Rosas dealt harshly with youngsters who violated legal and social conventions. In 1847, Camila O'Gorman, the daughter of a prominent merchant, and Ladislao Gutiérrez, a Catholic priest, caused a huge public scandal when they ran away together. The following year, the couple was captured. Rosas personally ordered their execution for violating the social order. According to the dictator, their actions were a direct attack on his authority and that he wanted to make an example out of them.

Camila's story is often seen as an example of the extreme measures the Rosas state took to control the behaviors of Argentina's younger population. Indeed, Rosas wanted to make an example out of the young couple. However, this story of forbidden love is also representative of how young people challenged authority as ideas of republicanism, equality, and individualism swept through the Americas. The execution of the young couple (along with the fact that Camila was eight months pregnant at the time of her death!) undermined support for the Rosas regime. Moreover, Camila's story resonates even today as a reminder of the legacy of authoritarianism in Argentina's history. María Luísa Bemberg wrote and directed the feature film, Camila (1984), as a harsh critique of patriarchy and military rule.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

This teaching module incorporates a variety of primary sources that shed light on the shifting boundaries of parental roles and expectations, young people's behaviors, and social status in early to mid-19th century Argentina.

One strategy is to divide the sources into two sets. The first set might include evidence on the expectations that both parents and political leaders had for children. Parents, especially fathers, in early 19th century Argentina wanted their children to marry for particular strategic reasons (e.g., to maintain wealth across generations) rather than for romantic love. In addition, Argentina's leaders sought to socialize children by closely regulating dress, public behavior, and education. Young people today should have little difficulty understanding the weight of parents' expectations on their lives and the rules that authorities create to govern their conduct. Thus, it might be a good exercise to relate these ideas to the students' lives.

A second set of documents would be organized around the variety of ways in which Argentina's youth responded to the rules and regulations that governed their lives. The evidence from the era shows that young people adopted a variety of political viewpoints. Manuelita Rosas's portrait, for example, represents one way in which young people supported the regime. However, legal documents reveal the willingness and capability of young people to use the court system to advance their interests, which were often at odds with those of their parents. Camila's story demonstrates one young person's challenge to both parental and state authority. This evidence not only demonstrates sharp generational differences but also how legal institutions became increasingly involved in family matters as parental authority began to wane.

Examining official records, however, presents special challenges. For example, legal language may be confusing, and biases may be difficult to detect. Nevertheless, it is possible to make sense of these documents by following some general advice.

First, it is necessary to understand that the primary role of civil courts in any adversarial system is to satisfy demands. Typically, this involved two parties, who were recognized as legitimate groups before the courts. Children or their legal guardians had the right to sue, especially when property or transfer of wealth was involved.

Second, gather basic information from the document about what happened. The "facts" of a case might be incongruous with our own understanding of prevailing norms and practices. For example, students today might have a hard time reconciling the fact that people in their early 20s were still considered minors.

Discussion Questions

- What areas of young people's lives did parental and state authorities try to control in Argentina during the early 19th century?

- What strategies did young people in early 19th-century Argentina use to resist parental control?

Document Based Question

by Janelle Collett

(Suggested writing time: 50 minutes)

The following question is based on the documents included in this module. This question is designed to test your ability to work with and understand historical documents.

Drawing on specific examples from the sources in the module, write a well- organized essay of at least five paragraphs in which you answer the following question:

- What ideals did the Rosas regime promote for the youth of Argentina? How did the regime enforce those ideals and how did the youth combat them?

- have a relevant, clear thesis that answers the question,

- use at least six of the documents,

- analyze the documents by grouping them in as many appropriate ways as possible, not simply summarize the documents individually, and

- take into account both the sources of the documents and the creators' points of view.

Your essay should:

Be sure to analyze point of view in at least three documents or images.

What additional sources, types of documents, or information would you need to have a more complete view of this topic?

You may refer to relevant historical information not mentioned in the documents.

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Jessie Hingson is an Assistant Professor of History at Jacksonville University in Jacksonville, Florida. He received his Doctorate from Florida International University and is the author of several articles on the history of race and family in post-independence Argentina. His work has been supported by grants from Fulbright, Rotary International, and the Department of Education.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Janelle Collett is the chair of the History Department at Springside School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where she teaches seventh grade World History, ninth grade World History, and electives on the history of violence and nonviolence. In January of 2006, she was a member of an American History Association Conference panel, "Teaching the Nation as Imagined Community: Strategies for Understanding Nationalisms in the Classroom," and she has presented in a variety of settings on effective uses of technology in the classroom.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following institutions for primary sources:

- Archivo General de la Nación,

- Archivo Histórico de la Provincia de Buenos Aires,

- Archivo Histórico de la Provincia de Córdoba,

- Planeta Publishing,

- Scholarly Resources,

- Stanford University Press, and

- Taurus Publishing

This teaching module was originally developed for the Children & Youth in History project.