Long Teaching Module: African Scouting (20th c.)

Overview

Conceived by General Sir Robert Baden Powell to reduce class tensions in early 20th-century Britain, the Boy Scout movement evolved into an international youth movement that offered a romantic program of vigorous outdoor life for boys and adolescents as a cure for the physical decline and social disruption caused by industrialization and urbanization. One of scouting's main goals was to create social stability by dealing with the complex problem of adolescence. Every generation fears that the generation that comes after it will not respect its rules, values, and division of property. As a uniformed and disciplined youth organization, the Scout movement taught young males in the difficult years between childhood and adulthood to respect older generations and accept their place in society. By the 1920s most of the nations of the world had embraced the movement as a way to teach young people to be loyal to the state and respect their elders. While governments worldwide utilized scouting to reinforce political and social authority, such was not the case in colonial Africa where marginalized groups and social outsiders used scouting to challenge dominant institutions. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, potential adaptations, and essay prompts relating to the eleven primary sources.

Essay

Introduction

Conceived by General Sir Robert Baden Powell to reduce class tensions in early 20th-century Britain, the Boy Scout movement evolved into an international youth movement that offered a romantic program of vigorous outdoor life for boys and adolescents as a cure for the physical decline and social disruption caused by industrialization and urbanization. One of scouting's main goals was to create social stability by dealing with the complex problem of adolescence. Every generation fears that the generation that comes after it will not respect its rules, values, and division of property. As a uniformed and disciplined youth organization, the Scout movement taught young males in the difficult years between childhood and adulthood to respect older generations and accept their place in society. By the 1920s most of the nations of the world had embraced the movement as a way to teach young people to be loyal to the state and respect their elders. While governments worldwide utilized scouting to reinforce political and social authority, such was not the case in colonial Africa where marginalized groups and social outsiders used scouting to challenge dominant institutions.

Scouting began in 1907 with Robert Baden-Powell's creation of a youth organization aimed at promoting physical, moral, and imperial fitness among British youth by capitalizing on their fascination with "frontier woodcraft" and "tribal" life. He incorporated these elements into scouting in order to inspire young Britons to emulate what he interpreted to be the most praiseworthy aspects of African life. A diverse and eclectic mix of tribal peoples that included Amerindians, Arab Bedouins, and New Zealand Maoris served as inspirations for the movement, but Africans occupied a central place in Baden Powell's thinking. A 20-year career fighting colonial wars made him a self-proclaimed expert on "tribal" cultures, which he claimed to have incorporated into the scout movement.

At first, Baden-Powell did not have a specific ideology for scouting. But eventually several key themes emerged in his thinking and became the central core of the scout creed. Concerned that urban slums and vice were undermining British security, he aimed to prepare younger generations to defend their nation and empire. Just as life on the imperial frontier taught virility, resourcefulness, and self-control, scouting was a "school of the woods" that would instill these same ideals in British youth. By adopting the values and discipline of "tribal" peoples, scouting would teach the vital manly qualities that consumerism and materialism had drained away from "civilized" western society.

Similarly, Baden Powell also believed that class tensions led to national weakness. He therefore envisioned scouting as a way to teach working-class boys to accept their place in society by stressing obedience, discipline, and simplicity. This helps to explain the Fourth Scout Law: "A Scout is a Brother to every other Scout." Baden Powell never intended for this brotherhood to lead to social equality; rather it was a sense of fraternity in scouting that would defuse social tensions by reducing friction between rich and poor boys.

In the tense years before World War One, the movement's critics charged that scouting secretly prepared young men for military service. Baden Powell emphatically denied the charge, and after the war he recast scouting as an international peace movement. More significantly, he also acknowledged that non-Europeans could also be scouts and gave his blessing to administrators and educators who introduced scouting throughout the empire to teach imperial loyalty, encourage African and Asian students to accept their place in colonial society, and reduce the political and social friction that came with foreign imperial rule. By the inter-war era, colonial administrators and educators had begun to fear that student unrest, urban migration, and juvenile delinquency were products of a growing social crisis in local African communities. British administrators relied on local allies and chiefs to govern the African majority, and they worried that the younger generation's rejection of their elders' authority threatened widespread political and social instability.

The Boy Scout movement promised to correct this imbalance by teaching students and city boys to respect colonial authority throughout the continent. In French-speaking Africa, Baptist missionaries in the Belgian Congo tried to substitute scouting for secret male initiation ceremonies, which they considered immoral, while Catholic educators sought to use the movement to train "Christian knights" to assist in converting the wider African population. Similarly, in the French colonies the authorities tried to use scouting to train a small African elite that would help them control the rest of colonial society.

In eastern and southern Africa, British officials claimed that the authority of their African allies stemmed from "tribal tradition." But they also introduced western schooling to train the young Africans to help run the colonies and to demonstrate that they were "civilizing" their "primitive" subjects. The scout movement never achieved a mass African following, but it targeted the students, juvenile delinquents, and urban migrants that were the greatest threat to British rule. Colonial educators and administrators worried that these "detribalized" Africans were politically dangerous, particularly when they flaunted "tribal tradition" and aspired to live a western lifestyle alongside European settlers. The colonial authorities turned to scouting to "retribalize" African adolescents by teaching them to remain in the countryside and accept the authority of their "native chiefs." Ironically, they looked to scouting to teach African boys how to be "tribal."

Yet Africans also used scouting to claim the rights of full citizenship. They invoked the Fourth Scout Law, which declared a scout was a brother to every other scout, to challenge racial discrimination. Rather than making colonialism run more smoothly, then, scouting offered African boys a way to resist the discriminatory laws and social barriers that made them second-class citizens. Rejecting the authority of official colonial scout associations, they formed their own unauthorized troops to claim the power and legitimacy of the scout movement for themselves. Scouting was thus both an instrument of colonial authority and a subversive challenge to the legitimacy of the British Empire. The African Scout experience thus demonstrated how marginalized groups and social outsiders could use the movement to challenge these very same institutions.

Baden Powell would have been dismayed by how these independent troops twisted and reinterpreted the scout canon to demand rights, respect, and eventually independence. In Kenya, some African troops ventured into politics during the early 1950s by supporting the anti-colonial Mau Mau rebellion, which was essentially a civil war between landless Kikuyu young men and the wealthy Kikuyu chiefs and landowners who were allied with the British colonial regime. While some African boys who wanted to join the movement illegally acquired uniforms they donned, others used scout clothing to exploit the colonial authorities' assumption that they were trustworthy. Dressed as scouts, they could travel more freely about the colony and were often able to collect money for "scout" activities. Scouting thus simultaneously bolstered colonial authority and challenged the legitimacy of the British Empire.

Despite the challenges they posed during the 1950s, most territorial scout associations in Africa grew and prospered by allying with the colonial authorities. European scout leaders demonized African nationalists and were caught by surprise when these men came to power after independence in the early 1960s. It seemed likely that the movement's close ties to British imperialism would lead to its demise in post-colonial Africa, but the Africans who inherited control of the scout associations reinterpreted the scout canon to transfer their loyalty to the new nationalist regimes. The survival of scouting in the nationalist era thus demonstrates that the movement's vulnerability to re-interpretation by outsiders was also one of its great strengths. Once the new lines of political authority were clear, the scout associations made African nationalist regimes the focus of their second law ("A Scout is Loyal"). Even modern South African scouting, which lost popular African support for its unwillingness to challenge apartheid, has successfully reinvented itself as a force for economic and social development in the new South Africa.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

The Boy Scout movement exposes the tensions and divisions in any given society. Official scouting seeks an alliance with authority, and scout leaders interpret the scout canon to reflect prevailing values and social norms. Conversely, unofficial local modifications of scouting can express political and social opposition. National scout associations usually prevail in the struggle to define scout orthodoxy when their ties to political authority remain intact. Problems arise when the political and social terrain shifts before official scouting has time to react. As a result, scout authorities have become embroiled in controversies ranging from the civil rights struggle in the American South, nationalist resistance movements in India, and the contemporary American debate over gay rights.

In colonial Africa, scouting exposed the hypocrisy and instability of British imperial rule. Administrators and educators hoped to use the movement to teach young Africans to accept their subordinate place in colonial society, but the Fourth Scout Law, which declared that all scouts were brothers, gave Africans the means to reject this second-class status. Thus, the two central themes that emerge from colonial African scouting are: 1) the movement's official role in imperial governance and administration, 2) African moves to take scouting over for their own purposes.

Discussion Questions

- What was the official purpose of the scout uniform? Why would boys in general, and African boys in particular find it appealing? How did the scout uniform and badges both reinforce and disrupt British colonial rule in Kenya and South Africa?

- Why did the South African Scout Association force African boys to become Pathfinders instead of regular scouts? How did the segregated South African scout movement reflect the larger racial divisions in South African society? Why did Africans find the movement appealing despite its official ties to the apartheid regime?

Lesson Plan

Lesson Plan: ".. . And a Brother to Every Scout."

by Elizabeth Ten Dyke

Time Estimated: three 50-minute classes

Objectives

- Discuss the influence of colonial experience on Baden Powell's decision to found the Boy Scouts

- Describe activities related to scouting in Africa

- Explain how a cultural tradition (scouting) can express social conflict and political struggle in a particular time and place.

Materials

Preparation

Take the "Introduction" to this module and cut it into five sections—two paragraphs per section. Attach each section to a sheet of chart paper. Label the charts A through E. Post the chart paper around the room, or set each on a different desk or table.

Day One

Hook

Introduce the lesson by asking the students, "What do you think of when you think of the Boy Scouts?" Students may think of the uniforms of scouting, the rules and traditions, loyalty, activities such as camping, and awards including Eagle Scouts. They may mention Christian and anti-gay aspects of the scouting movement. Particularly if these subjects come up, ask students to speculate about how or why scouting has become an activity mired in disagreements about moral issues in our society today.

Instruct

Explain to students that they will learn about the history of the Boy Scouts (when, where, and why it was founded). They will study primary sources that illustrate some of the tensions and conflicts that occurred when scouting expanded into colonial Africa. This lesson will help students see how cultural traditions can reflect complicated social situations in which different groups of people express disagreement and exercise competing interests.

Activity

Give each student a complete copy of the introduction. Break the students into five groups, one at or near each poster. Assign each group the two paragraphs of reading that correspond to their poster. After they have completed their reading, they should make a bulleted list on the chart paper in which they outline the main ideas of the assigned passage. Have each group present their summary in turn. Students who are listening as others speak should take notes on the material.

Discussion Questions

- Chart A (paragraphs 1, 2): What tribal peoples served as inspiration for the scouting movement? What was scouting supposed to teach the young people who participated in it?

- Chart B (paragraphs 3, 4): What concerned Baden Powell about his nation’s youth? What values did he hope the Scouts would learn through their participation? Explain the Fourth Scout Law "A Scout is a Brother to every other Scout."

- Chart C (paragraphs 5, 6): Explain how scouting became an international movement. How was scouting supposed to help British colonial authorities maintain their power in places like Africa?

- Chart D (paragraphs 7, 8): Which young people were targeted for the African scouting movement? Why them? Give two examples of how "Africans . . . used scouting to claim the rights of full citizenship."

- Chart E (paragraphs 9, 10): How did scouting become involved in the 1950 Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya? Explain what happened to African scouting after British colonial rule came to an end. Did scouting come to an end as well? Why or why not?

Homework

Working from their class notes, students should summarize information about how the basic values and goals were part of the Boy Scout movement early on. They should describe the goals of British colonial authorities as scouting was brought into Africa, and they should give one example of the way in which the Scouts went against British power.

Day Two

Activity #1

- Distribute copies of primary source: The Scouts' War Dance--Baden Powell's adaptation of a Zulu chant, c. 1910

- Distribute blank paper, colored pencils

Have students look at the introduction to this primary source. Point out that Tim Parsons writes, the "odd ritual" of the war dance "was just the sort of thing that Edwardian schoolboys loved for it allowed them to play at being Africans in a thoroughly modern context." Ask students to speculate about what the author means by this statement.

Have the whole class carefully read the description of the dance. Working in pairs, students should:

- Restate the different steps and parts of the dance in their own words.

- Draw or sketch an image of the scouts participating in this dance.

- Discuss what elements of the dance incorporate stereotypes about African culture.

- Discuss what elements of the dance incorporate scouting traditions.

As a whole class: share sketches and discuss "How would this dance help Baden Powell achieve some of his goals for scouting?"

Activity #2

- Distribute copies of primary source: "Appeal for African Scouts: Canon William Palmer to Imperial Scout Headquarters May 5, 1923."

Using a pen, pencil, or highlighter, underline passages in the letter that answer the following questions:

- Who is the author of the letter? To whom is it addressed?

- Where in Africa (what territory) was the author of this letter and his students?

- Why were the students not allowed to call themselves Scouts?

- What were they allowed to do?

- What are three points the author makes to demonstrate that this is unfair?

Homework

Respond in writing to the following question: "What does this conflict (over who may be a Scout) reveal or show about society in the Transvaal at this time?" Support your response with evidence from the document.

Day Three

- Discuss the previous day's homework, focusing on the ways students used documentary evidence to support their point of view.

- Distribute primary source: "Legal Protection for Scout Uniform 1935: Tanganyika Government Ordinance."

- Distribute copies of the "Fact or Fib?" worksheet.

Have students read the legislation with the worksheet in front of them. For each question on the worksheet, they should write a correct response (fact) and an incorrect response (fib).

The entire class should address each question in turn. The student who answers may give the correct response, or the student may give an incorrect response. The other students should listen carefully. If the response is correct they should call out "Fact!" If the answer is false, they should call out "Fib!" Then, when asked, a student who identified a fib may give the correct information.

Discussion

Based on your reading of this legislation, infer some of the problems that were occurring with Scouts in this time and place. In other words, what may have been going on that that government felt it was necessary to create this ordinance?

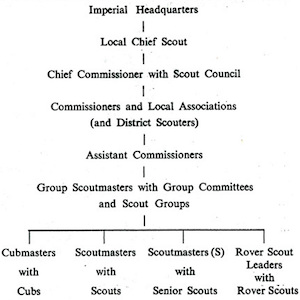

Distribute copies of primary source: "Organization of British Imperial Scouting" (table, 1951)/

As a whole class discuss:

- What are the four groups of troops at the bottom of the chart?

- How many levels of authority were above them?

- What was the highest level?

- What was the second highest level?

- What does this chart show about the relationship between the British Empire and Africa?

Day Four

Document Based Question Essay

Document Based Question

by Elizabeth Ten Dyke

(Suggested writing time: 50 minutes)

In the introduction to this unit, author Tim Parsons writes, "Scouting was thus both an instrument of colonial authority and a subversive challenge to the legitimacy of the British empire." In other words, scouting would "train" African boys to accept colonial power as well as empower Scouts to use the movement to resist or oppose colonial power. Write a well-organized essay drawing on evidence from three primary sources that helps you support this point of view.

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Tim Parsons is a Professor at Washington University. Parsons is the author of several books including: Race, Resistance and the Boy Scout Movement in British Colonial Africa; The 1964 Army Mutinies and the Making of Modern East Africa; The African Rank-and-File: Social Implications of Colonial Service in the King's African Rifles, 1902-1964; and The British Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A World History Perspective.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Elizabeth Ten Dyke has a Ph.D. in Cultural Anthropology. She is Director of Instructional Services for the Kingston City School District, and is the author of Dresden: Paradoxes of Memory in History.

This teaching module was originally developed for the Children and Youth in History project.