Analyzing Primary Sources on Women in World History

Overview

Traditionally, historical writing focused on elites and often rendered women invisible unless they were queens or empresses. With the socio-political changes of the late 1960s, historical inquiry expanded to include a focus on race, class, and gender. This literature has begun placing women’s varied experiences worldwide in historical context. This module is meant to introduce different ways to think of about women in the context of world history through a variety of different source types.

Essay

Introduction

All of these women are figures of historical importance in their own right.

- Queen Hatshepsut and Cleopatra of ancient Egypt

- Shaman-Queen Himiko, 3rd-century Japan

- Emperor Koken-Shotoku, Japan’s last reigning female emperor

- Queen Nzinga, who ruled in precolonial West Africa

- Queen Elizabeth I of 16th-century England

- Catherine the Great of 18th-century Russia

The history of women in the world more often includes names like these:

- Mumtaz Jahan, the wife of 17th-century Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan

- Eva Perón, the wife of 20th-century Argentine president Juan Perón

- Jiang Qing, the wife of Mao Zedong and member of the so-called Gang of Four

- Yang Guifei, the concubine of an early Tang dynasty emperor

These women reflected the importance of men with whom they were associated: husbands, fathers, sons, or, sometimes, consorts.

These women are all exceptional, in part because there are records that tell us about their lives and in part because they appear in world history textbooks. They all played important roles in economic, diplomatic, and political history and had formal or informal access to power.

Traditionally, historical writing focused on elites and often rendered women invisible unless they were queens or empresses. With the socio-political changes of the late 1960s, historical inquiry expanded to include a focus on race, class, and gender. This literature has begun placing women’s varied experiences worldwide in historical context.

Rethinking History

When studying the lives of women throughout history, it is important to consider the questions that have not been asked: “where are the women?” “how would the inclusion of women’s experiences enrich interpretations of the past?” and "why were the roles women played the subject of limited attention in, or omission from, particular historical discussions?" The traditional invisibility of women in history does not mean that they were absent from pivotal events or did not play important roles in their societies.

Consider, for example, how warfare often has been represented in history books: a narrative of battles and military prowess. The visual record of war—from the narrative on the “Royal Standard” of Ur, through those on vases, wall frescos, mosaics, and illuminated manuscripts, to the Bayeaux Tapestries in France—is overwhelmingly one of men fighting men. In many traditional histories, the dates of wars bracket the beginnings and ends of different eras.

As long as historians’ focus remained on fighting, the analysis of war centered on death and heroism, together with military hierarchies and strategies. Questions often raised in connection with war addressed issues of diplomatic, military, and political history. This interpretation of warfare is popularly reflected in the predominantly male figurative statues in memorials throughout North America and Europe. Women are only occasionally found, and those who are depicted are usually shown healing or mourning the dead.

Women were more easily omitted from analysis of the fighting front because, until World War II, when significant numbers of women participated as soldiers in the Soviet Union’s Red Army, they were only rarely found on or near the battlefield. Occasionally mythological figures like the Amazon warriors of Ancient Greece or Tomoe Gozen, the Japanese female samurai, or exceptional real women—such as Joan of Arc, the 15th-century French heroine of the Hundred Years’ War against England—became part of war legend. In rare cases, lesser-known women donned men’s clothing to participate in battle as males. Beyond that, only camp followers, and later nurses, would find places in this history.

What happens, though, when we change the focus? When we consider war as having both a home front and a fighting front? Then the discussion of war expands to include not only women’s varied wartime activities, but also the experiences of families, children, and noncombatant males. This approach permits examination of nonheroic accounts of the male experience of war, differing attitudes toward male and female collaboration and resistance, and postwar social continuity and change.

Standard primary sources, such as government documents and newspapers, contain a wealth of material reflecting women’s wartime experiences. These include accounts of civilian rationing and food supplies as well as statistics on birth, death, marriage, and divorce rates. Private sources, ranging from civilian letters to women’s commentaries about life on the home front, in captivity, or in exile, also help us understand wartime in a broader framework. Taking into account class, cultural, gender, and racial aspects of wartime society expands our understanding of the reach of war.

This example of how the history of war changes when we broaden our focus can be applied to any aspect of world history. When we take this broader view, women emerge from the shadows and become active and important players in our analysis of the past.

Considering the place of women in world history does not simply expand our understanding of events, but reshapes that understanding. Therefore, it is important to think about women, and gender more broadly, as more than adding voices to the historical record. By investigating women in world history, we gain a new way to understand social relations at every level—the personal and the political, the local, the national, and even the international.

What does the source tell us about society?

Investigating women in world history through the use of primary sources requires careful attention to particular historical contexts. Women’s lives have varied dramatically based on geography, religion, level of education, socioeconomic position, marital status, race, and historic time period.

Women have subscribed to many different political, social, cultural, or economic agendas, and these must be taken into consideration to understand women through primary sources. It is important to consider the factors that have rendered women in particular times and places different from women who lived in other situations. How have men and women used the language of gender—defining men’s roles as inherently “masculine” and women’s roles as inherently “feminine”—to structure society? When we look at these roles over time and across cultures, we see that the categories can vary dramatically. For example, British, male colonial officials in Nigeria misunderstood an uprising of women in Southeastern Nigeria in 1929. The officials were interpreting the women’s actions based on how they thought British women would act.

Carefully considering the specific experiences of women in particular times and places and the symbolic roles women have played in history, historians begin their analysis of primary sources by asking a few basic questions, all of which help place the source in historical context.

In a sense, all of the following questions are about social relations. It is also important to step back from the specifics of individual sources to consider how they contribute to a larger understanding of a society.

How does this source fit into what we already know about a situation? Does the evidence contained in this source suggest that we need to revise our understanding about women’s experience of an event or a place or a time period? How does this source compare and contrast with the information we have about women in similar social situations? How does the information contained in this source shed light on the ways that a society imagines itself and its interaction with those outside that society? How does this new information change what we know about the hierarchies of power within and among societies?

Textile production, for example, reflects the availability of products, including cotton, linen, and wool, as well as trading patterns, and sophistication in the production of the cloth itself. Textiles also provide information about female clothing as it relates to the age and economic and social status of the wearer, or its social function—whether or not is was used for cultural-religious ceremonies, or general use.

What kind of source is it?

Different types of sources offer various kinds of information. Official documents rarely contain information about personal and private issues, but they do provide evidence related to larger, more structural issues. For example, legal codes often reflect a society’s ideal vision for itself, whereas court transcripts provide a glimpse into situations of individual behavior considered unacceptable by the society. Personal narratives, in contrast, might offer reflections on larger social issues, but they are usually focused on events as they affect the life of one individual or the lives of several known individuals, rather than a nameless collective.

Careful reading of many kinds of sources can help identify important clues such as the language used, the tone of the source, and motivation of the creator. With visual material, considering the physical form of the source is an important step in analysis.

While many visual or material culture sources do not contain words, scholars analyze them in similar ways. Is the image realistic or figurative? Does it have characteristics that mark it as the product of a particular time or place? Does it draw upon common cultural references or styles? Was it created for a museum or other public use rather than for personal enjoyment?

Similarly, objects of material culture require close reading that considers the form and function of the source. What materials are used to create the object? Was it for everyday use or was it used in religious or social rituals? Is the object decorated? If so, what messages does that decoration convey?

When you first look at a source, you can attempt to identify it by asking some of the questions listed above. If it is a written text, read it, look for information about the author, date, and location to help ascertain the original purpose of the document. If the source is an image, attempt to answer some of the same questions by discovering its location of origin, its material, and its meaning and use at various times. This kind of information will help you decide how to analyze the document in question.

Who created the source and why?

Analyzing sources that pertain to women’s lives and experiences often starts with questions about author or creator and why something was created. Any author, male or female, brings a set of assumptions and values that shape the source. Understanding those assumptions and values is one of the first steps in understanding the source. If an author can be identified, a next step is to learn more about his or her life.

Some sources, such as official documents and newspaper advertisements, do not necessarily have an identifiable author. Nonetheless, they reflect the consensus of a group of creators, such as legislators, diplomats, newspaper owners, and marketing firms. These authors still represent identifiable perspectives that can help explain the sources.

Who is the intended audience?

In addition to identifying the author, identifying the intended audience or audiences is an important part of analyzing any source. Evidence on women in history can fruitfully be divided into “conscious” and “unconscious” sources. “Conscious” sources are materials that have a deliberate subject or audience, such as letters or memoirs. “Unconscious” sources are more ephemeral, items that were made for or by women for daily, personal, or household use. All of these can be studied to learn about the varied experiences of women throughout history.

There is a large difference between public communication—documents created to be read by unknown others—and private creation. Public communication expanded rapidly with the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, and later with the growth of the bureaucratic state across the globe beginning in the 19th century. Private materials are often created for the author, perhaps a journal or a painting, or for a specific other, perhaps a letter to a relative or friend.

In each instance, the creator of the material works with a particular audience in mind. The imagined reader—the self, a family member, other women, the general public—influences not only the content of the source, but also the form. Sources are created to persuade, to inspire religious devotion, to encourage “proper” conduct, to facilitate the day-to-day business of an organization, to preserve an account of a particular event or a particular life, or to provide statistical information about a group of persons or a historical phenomenon. In all of these cases, the author’s motivation shapes the content of the source, and subsequently, the evidence it provides about women in world history.

Types of Sources

There are many different sources one can use to analyze women’s role throughout world history. Explore the links to other World History Commons Methods for more information about using the following kinds of sources.

A valuable source for analyzing modern women’s history is quantitative evidence. It can help locate women within a greater society at the local, regional, national, and even, international level. Statistical data usually contains information about groups of women, categorized by factors such as age, race, location, or economic situation. These often reveal little about individual women’s experiences, but can offer rich information about women’s experiences as a group. This kind of evidence enables us to make transnational comparisons about the lives of women as well as comparisons with men, and can tell us about changes in a wide variety of women’s experiences over time.

Official documents of all types can help locate women in world history. They include government reports, laws, press releases, diplomatic communication, policy statements, declarations of war, treaties, constitutions, pronouncements of organizations, committee hearings, speeches, and court records. They show how societies viewed and treated women as a group, as well as expose women’s everyday lives. Often, piecing different official documents together can provide a clear picture of how different societies viewed women and women’s roles, and shed light on social structure as a whole.

Newspapers, especially dailies and weeklies, contain an enormous amount of information. Reading newspapers from different times and places, historians learn about current events from local, regional, and international perspectives. They also learn what is important to publishers and readers of certain newspapers at a given time. Historical newspapers allow scholars to analyze trends across time or compare coverage of daily events in different newspapers within a city or across the globe.

Religious sources are excellent sites for uncovering the important beliefs and frameworks that have influenced women’s experiences throughout history. Religious systems often provide a comprehensive way to think about aspects of life. Religions can provide information about how particular cultures organize their human relationships, how they make their personal and communal decisions, and how they interact with other societies.

Personal accounts are excellent sources for women’s history. These include travel accounts, diaries, memoirs, letters, and oral histories. These are more common in the last two centuries with the expansion of female literacy—throughout history most women (and men) were illiterate. While documents created for personal reasons often tell us about individual women, some of the attitudes they reflect and the experiences they discuss can be generalized.

Literary sources can provide useful information about women of a particular era or place in world history. Novels, short stories, and poetry created by women express their perspectives on a range of social and cultural issues. Although these texts are works of imagination, women have used them to voice their thoughts on a wide range of issues.

Music can provide an important window into the lives of women in world history. Music is best understood as “humanly organized sound” or “the purposeful organization of sound.” Many different types of music can be found in the historical record: music recordings, song lyrics, written music, spontaneous tunes, staged music performances, and music performances in other social settings, such as work situations and domestic life. Asking a few fundamental questions about a culture’s musical system can open up a unique window into the philosophical, religious, and artistic concepts that shape people’s everyday lives. These questions also can help you determine how societies viewed women’s roles and status.

Visual sources offer important evidence about gender in a society. Paintings, murals, sculptures, and mosaics often provide information about the positions of women in a particular society through representations of women, men, sexuality, class, diet, familial relations, religion, daily activities, leisure, and work. Women are also part of the visual record as artists.

Objects of material culture, such as clothing, textiles, cooking utensils, tools, simple machines, jewelry, or religious artifacts supply information on women’s everyday lives. They provide evidence about women’s positions in society, documenting not only their role in the household economy, which is often predominant, but also the social rites of passage in which they participated. Other items tell us about cultural and religious practices, some of which reflect attitudes toward women.

For more resources on using primary sources related to women in a world history course consult this syllabus developed by Merry Wiesner-Hanks.

Primary Sources

Sample Analysis

Case Study: Prostitution

We can learn a great deal about women’s history from studying women in a particular situation. Discussion of prostitution, a topic that has long excited widespread interest, incorporates ethnographic, historical, philosophical, medical, religious, and sociological elements and can tell us much about different societies’ attitudes toward women. Popular attitudes toward prostitution also provide information on a particular society’s beliefs about race, class, gender, and age, as well as eugenics and hygiene, not to mention gender difference in marriage. The variety of sources described here can be employed as a model for students interested in other women’s history topics.

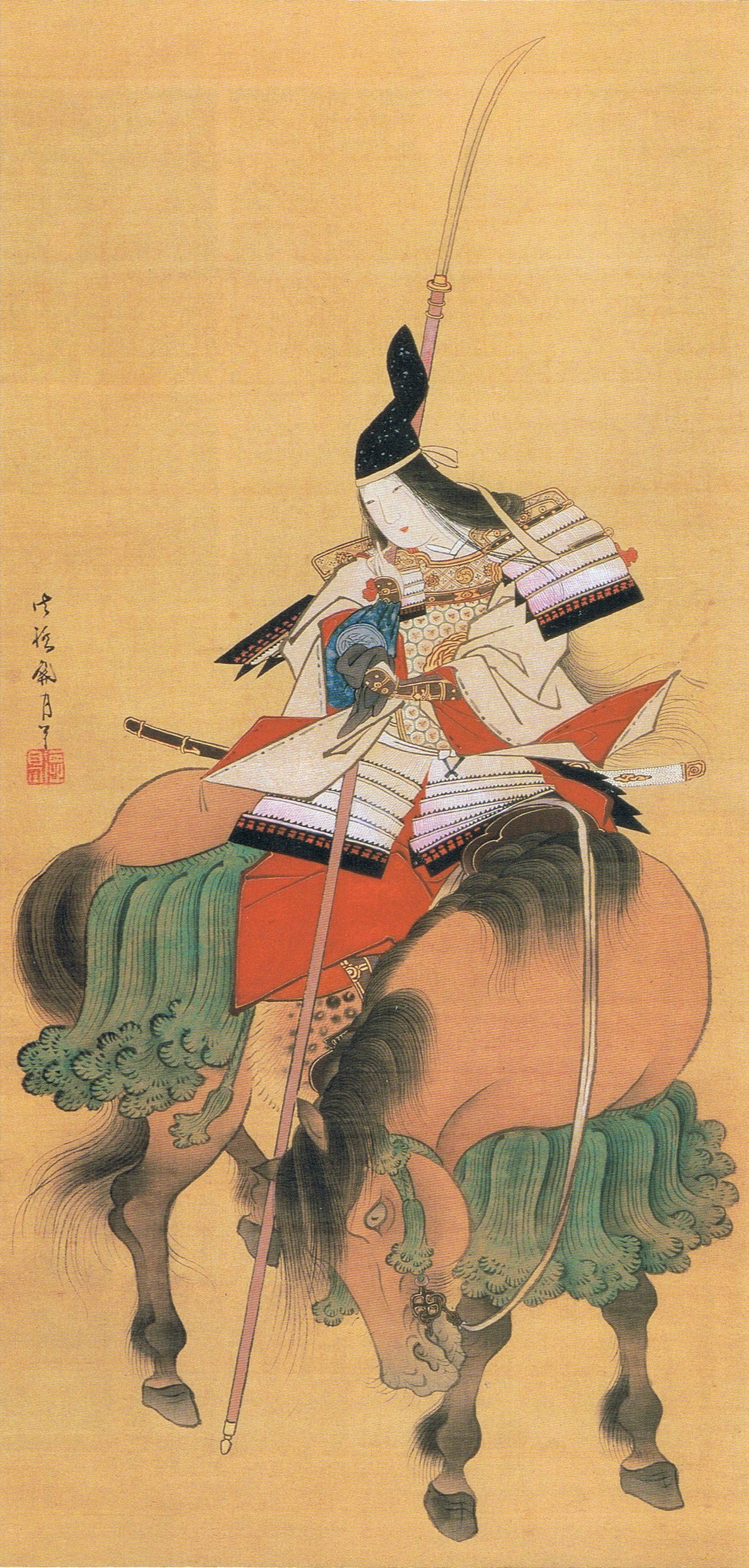

Courtesans, or upper-class prostitutes, are among the women often mentioned in traditional histories, from the hetaerae of Ancient Greece, through the Byzantine Empress Theodora, to Diane de Poitiers, the 16th-century mistress of Henri II, King of France. Courtesans have been the subject of Japanese woodcuts, “Pictures of the Floating World,” dating from the Edo Period, and of European portrait painters.

Some, like the Madame de Pompadour and Madame du Barry, the mistresses of French King Louis XV during the mid-18th century, came to wield significant power. These women, however, represent only a small percentage of prostitutes, many of whom lived—and still live—in poverty.

Both men and women have been employed as sexual laborers throughout history. When Western governments began attempting to regulate prostitution during the 19th century, however, their policies concentrated on the sexual behaviors of women. Journalists, moral crusaders, and politicians discussed prostitution in newspapers, periodicals, parliament, and public speeches or discussions. Novels reflected contemporary female stereotypes associated with prostitution (the “weaker” morals of women or the “dirtiness” of women from certain ethnic groups, often immigrants). Physicians, sociologists, and other specialists sought to explain its causes. Reflecting the growth of prostitution as a global concern, beginning in the late 19th century, countries throughout the world began signing international treaties banning the transportation of women for illicit purposes, which was known as the “white slave trade.”

Standing Prostitute in White Kimono,

early 18th century

European states, as well as some cities in East Asia (but not the United States), that regulated prostitution kept a close eye on “registered” prostitutes, who constituted a small percentage of sex laborers. Most sex laborers worked clandestinely, sometimes only temporarily.

Governments passed laws meant to control the behavior of prostitutes. Officials tracked their health with compulsory medical examinations designed to detect venereal diseases. “Morals” police monitored their behavior and movements, and arrested them for a variety of violations, sometimes resulting in court cases. All of these documents (laws, court records, police records, and health exams) provide a rich source basis for the study of prostitution.

In an era before antibiotics, venereal disease was the main cause of concern about the health of prostitutes. Because registered prostitutes might have as many as 20 clients a day, they risked great exposure to venereal disease (and other infectious diseases) and at the same time exposed many people to it. Indeed, by the time a registered prostitute was discovered to have a venereal disease, she might already have infected numerous clients, who might pass the disease along to a spouse or other partners.

In addition to local, regional, and state governmental documentation of the behavior of individual prostitutes, there are also the numerous publications by social organizations concerned with the issue of prostitution. Although many male and female bourgeois social reformers sought to eliminate prostitution altogether, their approaches were often very different, in part because of contrasting attitudes toward venereal diseases. For example, many reforming middle-class women’s groups in the United States asserted that the very regulation of prostitution discriminated against women and helped force them into a lifetime of prostitution; once labeled as prostitutes, their possibility of finding “respectable” employment was limited.

These varied materials reflect differing class, cultural, religious, and social perspectives on prostitution, especially in the modern, Western world. They tell us what observers thought about prostitution and how their attitudes changed over time. Until recently, there were few personal accounts by prostitutes to provide clues about their varying motivations or their attitudes toward the governments, organizations, or individuals that sought to regulate the practice or abolish prostitution. Oral histories as well as the anthropological and sociological studies that document the lives of prostitutes, many of them from Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe and almost all of them poor, have begun filling this gap.

Credits

Nancy M. Wingfield has published widely on the cultural history of Habsburg Central Europe. She was the editor of Creating the Other: Nationalism and Ethnic Enmity in Habsburg Central Europe (2003) and co-editor with Maria Bucur of Staging the Past: The Politics of Commemoration in Habsburg Central Europe, 1848 to the Present (2001). She was co-editor of Gender and World War in Twentieth-Century Eastern Europe, also co-edited with Maria Bucur in 2006, among many other works.