Analyzing Music

Overview

Everywhere you go, there it is.

Even when we are not listening, music is around us. It blares from radios and headphones, kicks off sporting events, energizes crowds at demonstrations, and intrudes on our shopping experiences. Just now, a tune tinkling from a passing ice-cream truck interrupted the writing of these words. The commercial marketing of recorded music has been a fact of life since the early 20th century. Its inescapable presence reminds us how music shapes almost every moment of our waking lives.

Essay

The daily barrage of sound makes it easy to forget that music has amazing powers as well. To demonstrate this, think of the last film you saw and enjoyed. Try to imagine viewing it without the music. Is something missing? Now, try to imagine attending a wedding, a funeral, or birthday party where no one is singing, nor is any kind of music being played or performed. You’ll find that not only is it impossible to imagine such an event taking place, but that something about the quality of the experience seems to fade—as if you were seeing a color film in black-and-white.

But music is more than a component of other kinds of activity. When we delve deeper into even one kind of sound that surrounds us on a daily basis and grapple with its meaning, we get a unique opportunity to travel through other kinds of experiences and perspectives. This kind of inquiry—studying music through the ears and eyes of the people who make and consume music—is called ethnomusicology. You can use some of the ethnomusicologist’s tools to uncover the historical and cultural significance of any musical event you may encounter.

What Makes Music 'Musical'?

It’s music to my ears.

That’s not music, it’s noise.

Turn down that noise!

What is music? How do we know what’s musical and what’s not? Why is music music to some ears and noise to others? Everyone thinks they know music when they hear it, but few can say exactly what it is and why. If you’ve ever been on the receiving end of a command like “turn down that noise,” you know how slippery ideas about music can be.

Few have succeeded in truly defining music. Imposing a single definition on all of the world’s music is difficult because people’s opinions differ about what music is and what is musical. Many scholars of “world music” study behaviors and sounds that are not considered to be “music” by the people who make it—the chanting of the Koran, for instance. It’s our job to figure out a way of studying music that makes sense to the people who make it. Rather than trying to come up with a definition of music, we look for a concept of music that works for the culture we study. Here are a few that are likely to work for any music.

1. Music can best be understood as “humanly organized sound” or “the purposeful organization of sound.”1

2. Music is a form of communication. Music has much in common with language, and the two are almost inseparable as ingredients in popular song, opera, and other musical forms. The relationship between music and language has been an important part of the human musical experience since prehistoric times.

3. Music is difficult to describe in nonmusical means (i.e., words). As Elvis Costello has observed, “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.”

4. People’s concepts of music do not always match the way they perform and experience music. For example, societies may claim that music is highly valued, but deny artists a livelihood, persecute them politically, or call them a danger to public morals. Asking questions and comparing answers about the activities and social status of musicians is key to the informed study of music.

Many music lovers insist that music is best appreciated if we do not define it, analyze it, or expect it to communicate anything at all. So what does music have to tell us? Why study music? Music offers a record of history and human experience that words and images cannot. This record is especially important in nonliterate societies, or in cultures where colonization, war, and social rupture have interrupted the transmission of written history.

Second, music has a unique ability to convey memory. Both song texts and tunes can remind us of people, places, and events, accessing an ancient “hard drive” of historical memory. In my own study of elderly Jewish immigrants, singing particular songs in the Yiddish language helped them retrieve important recollections from their past. It made it easier and less painful to recall their experiences in the Holocaust, and as refugees in New York City and Israel. Certain songs situated them (and me, their listener) at a specific place in time, conquering the inadequacies of historical facts and events to describe a particular situation.

We must always respect the fact that for many people music is just music, and it acts on them in ways that are personal and individual. Yet ethnomusicologists have found that music is often “implicated,” or repurposed for different ideas and agendas beyond its original conception. For example, Richard Wagner’s music was used by Nazis to express notions of Aryan supremacy in Germany. Music has been used to strengthen the power of governments, sell cars, foment revolution, and convert souls to a particular religion. Music does not just act as a mirror of the culture that created it; it “performs” that culture.

Who is Making the Music?

Asking questions about the makers of music can be revealing. We often identify and describe music makers in a way that reflects our own values and experiences. In the Western classical music tradition, the composer is often seen as an all-powerful creator. Scholars studying Western music can see some of the concepts of genius and individualism that helped to shape post-Enlightenment European culture by studying the way certain composers are honored and revered.

In many societies throughout the world, composers are not placed on a pedestal and musical “talent” is not believed to be possessed by only a few fortunate souls. For the Kaluli of Papua New Guinea, the songs of birds are expressions of deeply-felt sentiments. Performing these songs is crucial for carrying out a variety of important ceremonies, from weddings to food distribution. In singing these songs, people all take their part in a musical pattern that connects them to the natural world and provides emotional release. Therefore, to get through life—to get through the day—everyone must be some kind of composer or musician. A similar principal is at work among Asian Americans who participate in karaoke singing. In this tradition, the act of participating in the karaoke performance is considered to be more important than how well someone can sing. In learning to replicate beloved popular songs, the individual becomes part of a historical continuum symbolized by the act of repetition.

When first approaching a culture’s music, you might set out to identify who the “musical experts” are, what they do, and how people evaluate their skills and personalities. Among the Mande people of West Africa, experts in speech and song are highly valued as advisors to kings and guardians of history as well as artists. These male artists, known as jaliya (singular, jali) inherit their craft from their fathers. Jalis memorize elaborate genealogies and heroic stories. Before the modern era, they commanded the respect merited by a learned person and had significant duties in the affairs of state. In a nonliterate society, a jali’s performance was once the only way the historical past could be brought in close contact with the living. British rule reduced the wealth and power of the royals and the jalis alike. Yet these performers (seen at weddings and other social occasions) helped the Mande people to retain their music as an important aspect of their culture.

It is also important to ask questions about how these musical experts are regarded. What is daily life like for musicmakers? Are they allowed to make a living at their craft? Are they given special status, or treated like pariahs? In some parts of India, composers and musicians constitute separate castes of people who must endure a lower social status. In a place where music is made not by local citizens but by “outsiders” and “others,” in places where musicians and composers are subject to controls and restrictions, there are key questions to ask about the power relations that shape their lives and their music.

Who listens to the music?

Listeners also participate in making music, whatever their role—passive or active; knowledgeable insiders or musical “tourists;” glued to their headphones or dancing in the aisles. Asking questions about who is listening and how can be quite revealing. In staged concerts, music is often performed for audiences other than those for whom the music was originally created. Performing for audiences other than the “original listeners” can help to change the music itself. In 1989, a group of choral singers from Bulgaria performed for an eager crowd of “world-music” enthusiasts at the Lisner Auditorium in Washington, D.C. A colleague brought me backstage to meet the performers. Through a translator, I asked one of the women how they were enjoying their tour of the United States. “It’s wonderful that people want to hear this music,” she said. “But I still am not used to singing in that voice on a stage.”

The singer was referring to the piercing, penetrating “outside” voice that women use when singing their songs in the meadows of their homeland. Her comment reminds us just how important the listener can be in shaping a musical performance. If we traveled to a village in Bulgaria where young women gather with their friends in a tight circle, shoulders touching, to sing the songs they know from childhood, we would be listening to their music in its intended setting. Chances are you would not be just listening, but also participating. There are no “audiences” at such gatherings because everyone present is expected to sing. If you don’t know the tune, you may be asked to “drone” a part, holding a single note while another singer adds a melody above it. How is the experience different when listening to this music in a concert hall?

When the venue and the audience are different, musicians adapt by changing aspects of the performance. Musicians in concert halls often have to adjust the length of pieces they perform. For example, in Java, musicians perform in all-night shadow puppet plays. When they are invited to perform at Lincoln Center, they must keep in mind the audience’s expectations of a two-hour concert performance, not to mention the stagehands’ union contracts. Changes are also made in the music when musicians perform outside a formal concert hall, such as at a street fair or a social event, to provide atmosphere—such as Caribbean musicians staging a limbo contest at a corporate fundraiser.

Adapting to the recording studio environment, in which the sound engineers and their microphones run the show, raises a very different set of questions about how technology intervenes in our listening experience. In the early days of recorded popular music, blues, jazz, and rural music performers adapted to the four-minute song length (the “side”) imposed by the limitations of the 78-rpm recording.

Likewise, most listeners adjust their ears and eyes in some fashion. In church and onstage, an audience for a gospel performance often joins in the show, shouting back encouragement to their performers such as “Amen!” or “Oh, yeah!” Outsiders to a tradition often frame what they hear in terms of their own life experience. If we are aware of how we listen to music—if we listen critically—we can narrow the distance between a musical event and its “foreign” performance setting. However, we need to keep in mind how performers expect us to listen—do they want us to sit still or tap our feet? Is this music for dancing? Do people in this culture have in mind a “right” way to listen to this music or is it considered to be music for everyone? Understanding the listening experience can help us fully appreciate the setting of a musical event and what this music is supposed to mean.

What is the musical system?

Your school’s marching band is gathered on the football field, ready to play. Each note they perform, every rule, custom, and procedure they follow—from watching the conductor’s baton to having their uniforms pressed—is a part of what ethnomusicologists refer to as a musical system.

When you approach a new kind of music, find out what vocabulary is used to describe it. Much music can be said to contain the following elements:

- rhythm, the purposeful organization of sounds in time

- melody and harmony, the organization of notes

- form or formal structure of a musical piece; and

- timbre, or the sound quality and texture of instruments and voices performing the music.

These can provide a working vocabulary for discussing and analyzing any kind of music.

Start by listening to a piece of music several times through and make some observations about at least one or two of these musical elements. In this example from a Tuvan throat song, the issue of timbre comes to the fore. Timbre is not just a formal element of this music, but a key to the worldview of those who sing. Singers from Tuva point out that the different textures of their singing correspond to how they see and experience their rugged landscape: “mountain,” “nose,” and “chest,” and other textures related to the visual effect created by the sun setting on the steppe.

Asking a few fundamental questions about a culture’s musical system can open up a unique window into the fundamental philosophical, religious, and artistic concepts that shape people’s everyday lives. For example, drums and rhythm have always been a central part of music throughout the Indian subcontinent. Drums exist in a variety of shapes, styles, and sizes. They are played with sticks, hands, or fingers and they accompany dancing and singing.

One of the manifestations of the Hindu god Shiva is Natarja who represents the movement of the universe. The small drum in Shiva’s hand symbolizes the audible space that fills the universe, the sound of creative energy. So rhythm, drum, and music are manifestations of fundamental Hindu beliefs. At concerts of Indian music, audiences listen to drummers raptly and follow their complex rhythms in cycles. Western audiences, used to rhythmic patterns of two, three, or four beats, get “lost” while Indian listeners can follow these cycles (some more than half an hour long) with the greatest of ease, using hand gestures (a wave of the hand, a count of the finger) to track the divisions of metric cycles. These cycles reflect cultural ideas about time that are documented in writings on music from Vedic times (1500-1600 BCE). These writings express time through circular imagery, such as the wheel of a chariot, the sun, the eye, or the human life cycle.

As you ask questions about the musical system, find out how people learn music and how they acquire knowledge of their tradition. Is music restricted to certain people or transmitted through a master-apprentice system? Rarely is music open to “just anyone” who cares to play it. Professional musicians have a vested interest in setting standards and limiting their competition!

In India, musicians who want to play professionally must align themselves with well-respected family-based “schools” known as gharanas. Indeed, observing changes in this tradition, such as accepting nonhereditary students out of financial necessity, offers a unique angle on the fragility of family lineage in the modern world as well as the “revival” of Hindu culture among middle-class Indians in the post-Independence period.

How is the music performed?

As we have seen so far, music can incorporate so many levels of meaning, depending on who is making it and who is listening. We have already seen that music can express many different ideas and concepts through melody, rhythm, and words. Another important aspect of musical expression is performance. Music must be performed in order to exist. A piece of music isn’t just “out there” to be admired, like a painting. It needs to be recreated at each hearing. It cannot exist unless we are there to listen. The re-creation of the music—and what it conveys to audiences—is what ethnomusicologists call performance.

When a rock band takes the stage before a crowd of enthusiastic young people, or when a Javanese gamelan (court orchestra) presents a concert of intricate music played on expensive, exquisite bronze instruments before an audience of dignitaries, a society’s values, ideals, and self-image are put on display for all to see and hear. What the gamelan performs depends on context. In a private, intimate court setting, the gamelan displays the elegance and largesse of its patrons. In a Western urban concert hall, the gamelan helps to activate some curious listeners’ appetite for the “exotic” sounds of the East. Among Indonesians, the gamelan helps activate cyclical concepts of time and beliefs in reincarnation that predominate in the Hindu religion. Performance is the realization and presentation of music in its social and cultural context—values and ideas set in sensory form.

How do we identify the important elements of a musical performance? Imagine the last time you saw a live concert with a favorite artist or group. Remember the setting, the excitement of the crowd, or the feeling of seeing a solo artist play “acoustic” in a small club venue. Think about the audience, onstage chatter with the audience, the lighting and sound system, and what the artists were wearing. Now listen to the same group or artist on a recording using headphones. Everything that is missing is an important piece of performance. Consciously or not, singers convey values through behavior, dress, and attitude together with the sounds they are making. These elements of performance can change the meaning of the music itself.

What is a musical artifact?

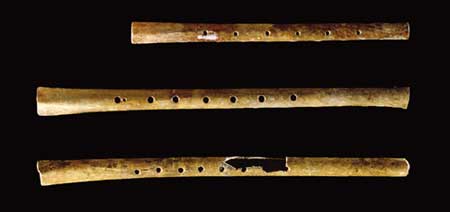

As we explore the nature of music, it is important to consider the objects that make the sounds: musical instruments. The use of musical instruments, such as clay flutes and bone whistles, has been traced back to the earliest documented historical period in China (Shang dynasty, 1765-1121 BCE). Instruments have since taken hundreds of thousands of forms and shapes. In the case of China (and in pre-Columbian civilizations as well), the discovery of ancient instruments such as ocarinas, or vessel flutes, are evidence of a sophisticated musical culture that thrived thousands of years before Europeans composed symphonies and operas.

In addition to serving as musical documents, instruments and the substances from which they are made have much to tell us about the landscape, natural resources, and the culture of the people who make them. For example, rainforest peoples of Africa and Brazil hand-carve panpipes and xylophones from wood, reflecting their special relationship with the natural environment. In America at midcentury, factories produced elaborately decorated accordions sporting bright colors and intricate grillwork. These tell us much about a postwar preoccupation with technological innovation, not to mention America’s love affair with molded plastics. Musical instruments also have a great deal of social and symbolic meaning within their communities. In the folk religion of Haiti (vodoun), certain kinds of gourd rattles are associated with spirits and are used to evoke them in religious ceremonies.

Ethnomusicologists have given a great deal of thought to describing and classifying the huge range of musical instruments. The Sachs-Hornbostel system divides instruments into five categories based on how sound is produced. For example, rattles belong to the category of idiophone, a “self-sounding” instrument. Accordions are aerophones because they make use of vibrating air. And Casio keyboards are kinds of electrophones.

As you explore music from different cultures, however, ask questions about how local people describe, classify, and name their instruments. Why do some jazz musicians refer to their saxophones and trumpets as “my ax”? Can instruments (and voices) be tools or even weapons that give their players a way of expressing hidden or suppressed ideas and powers?

Voices produce their own distinct sets of sounds. Each society has its own notion of what a “beautiful” or “good” voice is. Paying attention to these notions can reveal puzzling complexities and inconsistencies within a culture. Often we hear similarities in some traditions between vocal and instrumental production. Particularly fascinating are those traditions that imitate instrumental sounds through song, as in the “drum syllables” (vocal sounds such as din, din, da) with which Indian performers duplicate the special sounds of the tabla (frame drums).

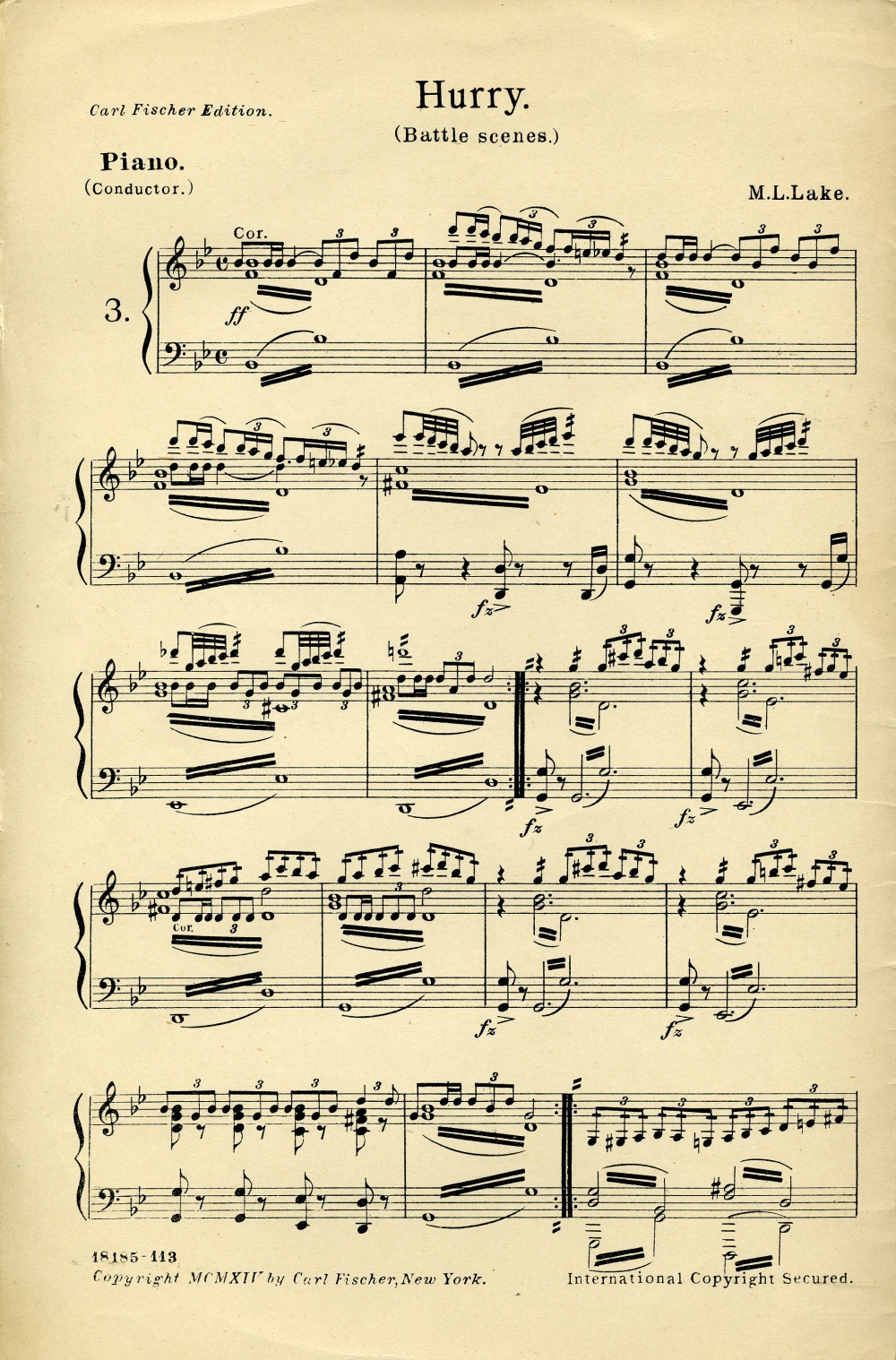

Almost every musical sound has been preserved on recordings in some form. Since the development of the phonograph in the early 20th century, recordings have joined the teacher, guru, or musical expert as key transmitters of music. The role of the recording in transmitting music has been particularly important where traditional music suffered a period of decline. A recording is one way that music can be preserved and transmitted in a durable, accessible form. As you learn about musical systems, look for other ways that people have tried to transmit music. In Europe, illuminated manuscripts were treasured and costly possessions, as much works of art as musical documents.

In analyzing processes of transmission, we need to be alert to the limitations of any mechanical or electronic means of transmitting music. Vinyl and the magnetic digital chip both have limitations. A recording, regardless of its sound quality, is only a document of a musical work as it was heard at one moment in its history (music scholars compare many recordings before they make comments on a particular musical sound or style). Comparing a variety of sources and documents is the best way to get a handle on any musical system.

Primary Sources

Sample Analysis

The Case Study: Steel Bands Battle in Brooklyn

By asking and answering these five basic questions, we can build a “mini-ethnography” of a musical community, drawing forth some insights into what music reveals about the culture that makes, performs, and listens to music. In Bedford-Stuyvesant, a thriving West Indian neighborhood in Brooklyn, late on a Friday night in August, one passes few people and many vacant lots. The air is still and damp, and the only sounds are the hum of window air conditioners and an occasional car alarm. Yet turning down Sterling Avenue, one is suddenly surrounded by the ringing sounds of several different steel drum orchestras, or steel bands. These community-based ensembles of tuned metal drums and assorted percussion instruments play lively melodies at a galloping pace. The people in these groups (pannists, or panmen and panwomen) devote the better part of summer to their bands and to perfecting their musical skills.

The focus of these efforts is organized public performances, and doing well at these is the most important objective of steel bands. To get ready for these performances, pannists raise money, promote their bands, and seek publicity. Bands work hard to impress one another and their audiences in order to raise their profile in the community.

One of the biggest events for steel bands in Brooklyn is Panorama. Originating in Trinidad, it is tied to the Carnival season and is best understood as a music competition embedded in a series of festive activities and performances. Carnival in Brooklyn is celebrated on Labor Day; allowing many Trinidadian New Yorkers who return to the island for Carnival to celebrate the event twice a year. Early in the summer, masquerade bandleaders and designers start planning their themes and costumes for Carnival.

Music is a major sphere of activity during the buildup to Carnival. As soon as one Carnival ends, composers of calypso songs (calypsonians) begin composing new songs that comment on current events, social trends, or male-female relationships, or explore the general theme of arts, creativity, and exuberant pride in Caribbean music and cultural heritage. The themes are reflected in these shouted lines from the calypso song “Music in We Blood” from the 2003 Carnival season:

“You can’t get away! It’s in your system! It’s in your blood! Turn on your radio and run! It’s like your DNA! You can’t get away!”1

The reference to radio clues us into calypso’s commercial viability. Once calypsos are released, they are immediately aired and played repeatedly on Caribbean radio stations on the AM dial.

Preparation for Panorama begins about six weeks before the event. Each band determines how many functioning pans it has, and how many players it needs. Bands then select their arranger, who in turn decides what the tune will be. Each band presents a single tune, and it must be a calypso from the current year’s carnival season. Rehearsals begin, pannists drift into the panyards, and there begins the long and arduous process of teaching the tunes by ear. A week or so before the competition, tuners blend (tune) all the pans. A day or so before Panorama, players give their pans a thorough going-over with window cleaner and rags to make them shine.

Panorama itself is a one-night event taking place the Saturday night before Carnival in the parking lot of the Brooklyn Museum of Art. Steel bands fill the area and many are busy holding last minute rehearsals. Crowds cluster. People are there to dance (“jump up”) to the sounds of pan. But Carnival isn’t until Monday. Here, it is the music that matters. At Panorama, band after band plays, and the event ends in the early morning. Judges select and announce the winners and award the prizes ranging from $10,000 to $15,000. All the prize money goes to the arranger. No pannist ever sees a cent.

Who makes the music? Who is listening?

Steel bands first appeared on the streets of Port of Spain and other Trinidadian towns. Their players, the creators of the early steel drums, were young males of African descent. They belonged to the “grass roots” of Trinidad, the unemployed drifters, the disenfranchised working poor. Steel bands often engaged in violent conflicts and were compared to street gangs. Later, following Trinidadian independence in 1962, an emerging middle class began to embrace the steel band as a valued cultural tradition. The pan-playing Trinidadians both of the Island and immigrant communities in Brooklyn (the Trinidadian Diaspora) today run the gamut of professions, ages, and interests. Here are a few people I met when visiting the panyards.

- Jeanette, 63, born in Trinidad; a grandmother and mother of a teacher of steel band, impresario, and “pan matriarch,” whose daughter is in a band. She considers the fellow band members to be her children, and she helps them by bringing food and raising money for uniforms, instrument tuning, and for the arranger’s fee, which can run more than $1,000 per Panorama season.

- George, 58, Jeanette’s husband; a pharmacist, pan enthusiast, and self-professed “panaholic” who practices each day after returning home from work at a local hospital.

- Tianna, a 16-year-old high school senior of African American descent.

These three “snapshots” suggest that the history of pan is taking a different turn from its roots in the rough-and-tumble working-class male culture of Trinidad. The majority of players in most of the bands are young, teenage women enrolled in local high schools. To people like Jeanette, whose parents forbade her to visit panyards when she was a girl, the present pan culture (which includes active retirees, students, and working people) is a welcome development.

Bands depend on independent arrangers. This person is in charge of selecting the tune, orchestrating it for steel band in the appropriate style, and teaching it to the band. Well-known arrangers are revered and regarded as musical celebrities inside and outside the Brooklyn West Indian community. They are well paid for their efforts.

Bands also depend on a coterie of supporters, fans, and fundraisers to succeed in Panorama. Rehearsals attract regular listeners and become social centers. Supporters of each band often dance in the yard for most of the evening,, and enjoy drinks and food. Enthusiasts check up on their favorite bands and make predictions about the upcoming contest. Panorama is local in its orientation. It is devoted specifically to the Carnival tradition and calypso music—the popular and folk music of Trinidad—and it hopes to convey pride in and enthusiasm for that tradition.

The most powerful listeners for Panorama are the judges. With their long checklists of criteria such as “modulation” and “dynamics,” they bring a specific set of sensibilities, similar to those that inform listeners of European classical music. They perceive pan music not just as Trinidadian heritage music, but as an art form that has transcended the local tradition to become part of the international music scene.

Pans as Artifacts

Each day when George—whom we met earlier in the panyard—arrives home, the first objects that greet him are a set of steel drums. Gleaming and displayed on racks, the pans take up an entire wall of the living room.

Like the piano positioned on the opposite side of the room, the pans are on display for visitors. They remind us that this family can afford a few expensive things (a good pan costs $500-800), has enough leisure time to play music, and has good taste (is it a coincidence that the pans match the chrome accents of the living room chairs?). These pans are there to be played , but because of their iconic power, these also function as powerful “signs” or “signifiers.”

Both George and Jeannette are aware that their favorite instrument embodies the ingenuity of their forebears in Trinidad. Early steel drums took shape in the 1930s and 1940s through the efforts of industrious young musicians who experimented with combining and manipulating castaway metal objects such as biscuit tins and oil drums. They know about the tremendous advances made in the tuning of pans and the expansion of the range and quality of the instruments. In the 1940s, “the father of the modern pan,” Ellie Mannette, developed an elaborate process which is now standard for making pans: the sinking of grooves in a pan with a hammer to create the different notes, the tempering of the steel by heating the pan in a fire, and the tuning of the notes by hammering the sections.

In George’s home, pans are symbolic of the family’s personal style, their identity and sense of themselves as cultured people. When the pans are on display in public, they are symbolic for the community that supports this tradition. Pans are closely linked with the musical traditions cultivated by African slaves working on plantations in Trinidad’s early colonial days. Forbidden to play drums, the slaves developed ensembles of bamboo sticks and other percussive instruments that allowed them to play a key role in the island’s annual Carnival celebrations.

Steel pans carry forward a deeply embedded African heritage, but also allow many Trinidadians, proud of their cultural sophistication, to participate more fully in the Western European classical heritage. In steel bands, pans are organized in various sections corresponding to the symphony orchestra. The tenor pans carry the melody. Rhythm pans play harmonies, “fills,” and accompaniments. They often jump to the forefront of an arrangement by playing challenging solo passages. The jumbo-sized 55-gallon oil drums are the bass section of a steel band. They are accompanied by a rhythm section—drum kit, timbales, irons, scrapers, cowbells, and various Latin percussion instruments—which is aptly known as the “engine room.”

The Panorama Musical System

Panorama is a concert, a social event, and a festive affair, but it is also a competition. Players are part of an arduous teaching and learning process that is unique to Panorama. Arrangers teach by rote. They begin by demonstrating the music, phrase by phrase, to the top players. They in turn must teach it to others within the sections of the steel band. The objective is for each pannist to perform each note exactly as taught. Unlike other kinds of Caribbean music, there is no improvisation. Rehearsals last six or seven hours, every night of the week.

A Panorama arrangement is an elaborate musical composition between eight and ten minutes long—double or triple the length of a calypso. Essentially, the arranger’s goal is to reshape the calypso into a magnificent new original, borrowing from the styles and music of American pop, Latin music (salsa and merengue), funk, jazz, and European classical music.

Most calypsos today adhere to the soca style, a genre of Trinidadian popular music developed in the 1970s. Soca developed in part as a local response to commercial American pop music (funk, disco, and R&B) and boasts a strong, highly syncopated bass line. In this example, a central rhythmic theme, a “riff,” is played by rhythm guitar, cowbell, and high-hat cymbal. The structure of the calypso consists of a verse and chorus which is repeated. This calypso has two “interludes” for dancing and a finale. The finale revolves around an upbeat improvisational vocal style similar to scat singing.

Listen to the calypso song "Music In We Blood" from the 2003 Carnival season:

Let us now turn our attention to how a skilled steel band arranger handles a calypso. The orchestras used for Panorama pieces are quite large, between 50 and 100 people. The typical Panorama piece has an expanded structure, consisting of an introduction, verse, choruses, variations on verse and chorus, and an ending. Bridges and vamps are used.

Listening to “Music in We Blood” as arranged by Ken “Professor” Philmore and following the chart below, we can hear how the calypso is transformed into a competition showpiece.3

Listen to "Music in We Blood" performed by the Sonatas at Panorama 2003:

0:00 Introduction

0:44 verse

1:09 chorus (two-part) and repetitions of second half of chorus

2:09 first variation of verse [punctuated by players shouting hey!]

2:33 repeat of verse

2:57 variation repeats

3:40 vamp in r&b style

4:36 key change C to F

5:00 2nd variation of verse in key of F, melody in cello pans

6:05 variation of vocal material

6:37 second half of chorus (Bb)

6:51 “jam”: repetitions and variations of melodic material (improvisatory style)

6:59 Bb to C major chromatic modulation

7:09 introductory material in key of G

7:15 verse in C (third variation)

7:38 chorus repeated (four-pan solo)

8:18 coda

How much of the old version of “Music in We Blood” is left here? Note that the restatements of verse and chorus are not literal repetitions, but loose approximations of their originals. This gives the arranger more leeway to decorate the melody with countermelodies (melodies playing against melodies), snippets of new tunes, and new riffs. Although this version of “Music in We Blood” is certainly not a vocal piece, the performers shout “Hey!” at 2:09. This signals the first variation of the verse, traditionally the most difficult and challenging passage in a Panorama tune. Now that the band has your attention (and hopefully, that of the judges), they can show off some fancy musical moves. Each of the sections is given the opportunity to perform a brief solo. At 6:51, the arranger lets loose with a “jam,” evoking the spontaneous rhythmic energy of Carnival while sticking closely to the Panorama conventions.

Philmore’s treatment of the syncopations in the chorus riff borrowed from the calypso is noteworthy.

In the calypso version, the riff is as follows:

In the Panorama piece, it is adapted slightly:

Both riffs are “syncopated,” they stress notes played on the weak beats. Syncopation is a characteristic of many African, African American, and Afro-Caribbean musics. In the Panorama tune, the arranger has balanced out the syncopation, making it less lopsided and easier to handle by a large ensemble. It infuses the finished product with a smoother style, suggestive of R&B or classical music, or both, depending on how you’re listening.

Other elements one finds in arrangements of calypsos for Panorama include shifting of keys, call-and-response patterns, crescendos and decrescendos, vamps, and scale runs. How many of these can you identify in “Music in We Blood”?

As commercial popular music, soca music and “socalypsos” (calypsos based on the soca style—most calypsos released in the last ten or 15 years) are mainly disseminated on recordings. Panorama pieces are sometimes recorded, but steel band recordings do not have wide distribution beyond the players and their fans. Steel band audiences prefer to see live performances because the performance setting is so compelling. In addition, recordings of these large ensembles are difficult and expensive to create. The concert culture of steel band performance may deprive steel bands of a permanent record of their activities to pass on to their fans, their community, and historians from later generations. If this is true, the ethnomusicologist’s toolkit—oral history, firsthand observation, and attendance at rehearsals and live performances—becomes even more essential in documenting the history of these artists in their local musical communities.

Fire in the Engine Room: Performance of Panorama

It is not enough for a steel band to play pan (or in local slang, “beat pan”) competently. They must cultivate an exciting and dynamic performance style. At Panorama, the entrance of the steel bands is climactic. Once a band is ready to play, the announcer states who they are, their tune, and their arranger. The pannists play frantically, dancing in place or jumping on their instruments as they play, and their supporters shout and applaud furiously.

Performance does not only take place onstage. Bands muster support through publicity for months leading up to the competition. Steel-band websites such as www.basementrecordings.com provide the central focus of this type of activity. Bands rely heavily on their promoters (often volunteers or members of their family) to spread the word. A cheering booster section at Panorama can make all the difference to the morale of the performers, and may help sway the opinion of the judges. Hence, bands not only perform their music, but their self-image as well. Artifacts such as publicity materials, websites, and news coverage are worth studying because they reflect the aspirations of musicians.

What does this photograph of one musician, pictured here apart from her instruments, seem to want to say to the viewer?

What does the music do?

A Panorama composition is a hard-working piece of music. It is created for a specific purpose—to win a contest. In that sense, its players are its “end users,” aware of the music’s role as functional art. Yet many players give up their summer for Panorama without expecting a win. Crucial to their participation are concepts of local creativity, struggle, and achievement. As several ethnographic studies of pan have pointed out, pannists perceive the steel bands—and the miraculous story of their instrument’s creation and development—as evidence of a distinctly Trinidadian or Trinidadian-American creativity. They like to be part of the evidence. At the same time, many people perceive the histories of steel bands as tied up with the struggle to build the Trinidadian nation up from a long history of slavery, colonialism, and poverty.

Many members of the Trinidadian community in Brooklyn face the added challenges of maintaining their culture while living as second-class citizens in New York City. From their perspective, beating pan—and all the sacrifices that need to be made to keep the steel bands going—are part of everything else that people do to become more independent financially, emotionally, and culturally. The fact that others (non-Trinidadians) have joined their efforts has enhanced the value of pan in raising the prestige of Trinidad and Caribbean-American culture in the wider world.

This case study has been an attempt to reveal the role of music and musicmaking in developing a single community’s cultural identity. The role of music in helping to shape national consciousness is not unique to Trinidadian Americans. Many other forms of music allow people to explore their values and experiences and various visions of themselves as they are seen by outsiders. Do the experiences of pannists in steel bands have anything in common with local choruses, folkloric music and dance ensembles, and musicians in your community? Do people prefer to pursue music through “official” musical institutions, such as symphony orchestras, ballet schools, or ballroom dance academies? Or privately at home, with keyboard, MP3s, and headphones? Now it’s your turn to be the ethnomusicologist.