Social Capital in World History: Lyon and Pittsburgh as Examples

Overview

Lyon, France, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, are connected by the thread of social capital, or people power. This essay situates social capital as an non-financial asset possessed by people who have little wealth, but who use a variety of strategies to facilitate community improvements. During the period between 1980 and 2010, minority citizens on the economic, social, and political margins found creative ways to build and use social capital in low-income communities in Lyon and Pittsburgh. Both cities operate under very different national contexts—housing programs in greater Lyon are heavily influenced by a strong central government; whereas in Pittsburgh, a lack of a strong federal response required residents to develop creative partnerships to leverage scarce public resources. In both cases, local actors influenced national initiatives through the use of organizing techniques, coalition building, and direct action within cities increasingly divided by space, race, and income.

Essay

This is a comparison of people in both Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Lyon, France, on the economic, social, and spatial margins who built and used power from the ground up, known as “social capital,” to improve their communities in the three decades between 1980 and 2010. A transnational examination of the similarities and differences of these two cities helps illuminate people’s resistance to discrimination and deprivation. It is also a story of resilience, as many residents of these communities have overcome great hardships and negative stereotypes.

Social capital is a valuable comparative framework for examining people from communities with differing economies, demographies, and backgrounds. Aside from their location at the confluence of two rivers, Pittsburgh and Lyon are vastly different cities. Lyon was founded in 43 CE as the Roman city of Lugdunum, while Pittsburgh was established by the British in 1758. They share industrial backgrounds, and in 1980, the two cities were of similar population sizes. But since then, Lyon’s population has grown to more than a half-million (mainly due to immigration), while Pittsburgh lost residents; its population now stands at just over 300,000. However, studying people’s responses to marginalization in both cities provides a window into how they marshal political, social, and economic resources to survive, thrive, and shape the outcome of their communities.

In addition to the fact that the two have never been studied in a comparative context, Pittsburgh and Lyon are ideal examples of what Bruce Katz and Jeremy Nowak (2018) call “metro sovereignty,” smaller cities independent of megalopolises like New York and Paris. Minority residents in Pittsburgh and Lyon share discrimination and isolation—what Wacquant (2008) calls “territorial stigmatization.” Social capital is analyzed through profiles of several individuals who creatively combat systematic discrimination created by state and private actors. Resident mobilizations occurred outside of the standard channels of organized labor and longstanding civil rights organizations. French immigrants and American community development leaders forged their own networks to challenge systemic failures.

My research is motivated by the opportunity to change perceptions about place. Media images of riots in French banlieues (suburbs) in 1981, 1990, and 2005, coupled with popular films, such as Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) and Ladj Ly’s Les Misérables (2019), in addition to scholarship, such as Mustafa Dikeç’s Badlands of the Republic (2007) and Loïc Wacquant’s Urban Outcasts (2008) do little to change perceptions of these areas. Likewise, in the United States, recent rebellions in Baltimore, Cleveland, and Ferguson, Missouri, are reinforced by books by Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton, American Apartheid (1993); William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears (1996); and Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis (1996). No doubt these communities face many hardships.

I highlight citizen control over their communities that not only reduces violence and crime, but increases wealth and enhance an area’s overall image. In Pittsburgh, social capital represents the ability of neighborhood residents to create community development corporations (CDCs) to organize neighbors, marshal financial resources, and control real estate. In Lyon, social capital includes the efforts of French citizens of North African origin to mobilize low-income people to demand legal protections, require that the state invest resources into their communities, and declare themselves equal players in the national identity of France. While the federal government plays a role in the regeneration of many low-income neighborhoods, the residents themselves ultimately sustain the long-term vision for the community. This narrative shifts the perspective from one where poor people are the victims to one where they are the arbiters of their own destinies.

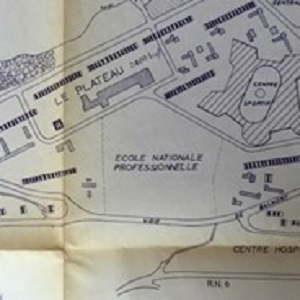

Communities highlighted include those which were the sites of violent riots in the Lyon region and, in Pittsburgh, symbols of postindustrial decay. In greater Lyon, I describe the social housing communities of Les Minguettes, in Vénissieux to Lyon’s south (site of a clash between youth and police in 1981), Mas du Taureau and La Grappinière in Vaulx-en-Velin to Lyon’s east (which was set alight in 1990), and La Duchére within the city of Lyon (location of a 1997 rebellion). Archival information, interviews with residents, and site surveys show improvements to the banlieues were the result of resident demands for improvement in these quartiers.

Similarly in Pittsburgh, I describe the community reinvestment movement which emerges in the late-1980s and early-1990s as a result of a coalition of community development leaders who redirect bank investments into low-income and minority neighborhoods. Within Pittsburgh, I focus on the city neighborhoods of Garfield, Bloomfield, Friendship, East Liberty, and Larimer, as well as the Hill District and Manchester—neighborhoods that were once redlined by banks and written off by city planners. As Tracy Neumann argues in Remaking the Rustbelt (2016), government, corporate, and foundation funding of community-based organizations created a “durable partnership.” But my story explains this transformation from below.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Lyon-based leaders such as Djida Tazdaït and Toumi Djaïdja formed associations to combat violence against immigrants and first-generation French citizens of Algerian origin. They also put a more positive face on the youth of the cités, the suburban high-rise towers that became associated with lawlessness and disorder in the minds of the French public. During the same period in Pittsburgh, CDC executives such as Stanley Lowe and Rhonda Brandon of Manchester, Aggie Brose and Rick Swartz of Bloomfield-Garfield, and Karen LaFrance of East Liberty negotiated multimillion-dollar deals with banks to increase private capital in redlined neighborhoods. New loan products and creative marketing programs, such as the “Ain’t I A Woman Initiative,” yielded an increase in black homeownership in Pittsburgh.

These developments had varying degrees of success on both sides of the Atlantic. But by the 2000s, communities in Pittsburgh and Lyon found themselves struggling with gentrification and widening inequality between rich and poor. Lastly, this type of study suggests pathways to create effective public-private partnerships that include the voices of low-income people and minorities in the sustainable and equitable development of metro regions.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Saul Alinsky, Rules for Radicals: A Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals. New York: Vintage Books, 1971.

Paul Brophy, ed., On the Edge: America’s Middle Neighborhoods. New York: The American Assembly, 2016.

State-driven versus people-driven Policies

Herrick Chapman, France’s Long Reconstruction: In Search of the Modern Republic. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Allen Dieterich-Ward, Beyond Rust: Metropolitan Pittsburgh and the Fate of Industrial America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Allen Dieterich-Ward, “From Satellite City to Burb of the ’Burgh: Deindustrialization and Community Identity in Steubenville, Ohio,” in James J. Connolly, ed., After the Factory: Reinventing America’s Industrial Small Cities. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2010.

Mustafa Dikeç, Badlands of the Republic: Space, Politics, and Urban Policy. Malden, Ma.: Blackwell Publishing, 2007.

Daniel Holland, “Communities of Resistance: How Ordinary People Developed Creative Responses to Marginalization in Lyon and Pittsburgh, 1980-2010,” University of Pittsburgh Dissertation, 2019.

Howard Gillette, Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005.

Michael R. Geenberg, Restoring America’s Neighborhoods: How Local People Make a Difference. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1999.

Social Capital and Capitalism

Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (1974).

Chris Butler, Henri Lefebvre: Spatial Politics, Everyday Life and the Right to the City. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Tracy Neumann, Remaking the Rust Belt: The Postindustrial Transformation of North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Robert D. Putnam, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Robert D. Putnam. “Tuning In, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America” PS: Political Science and Politics 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1995), 664-683.

Robert Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

Lawrence Vale, Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

State structures, Policies, and the Urban Environment

Loïc Wacquant, Urban Outcasts: A Comparative Sociology of Advanced Marginality. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2008.

Dave Waddington, Fabien Jobard, Mike King, eds., Rioting in the UK and France, 2001-2006. A Comparative Analysis. Abington, UK: Willan Publishing, 2009.

Comparative Studies of Global Cities

Derek Hyra, The New Urban Renewal: The Economic Transformation of Harlem and Bronzeville. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Impact of Globalization on Local Communities

James J. Connolly, After the Factory: Reinventing America’s Industrial Small Cities. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2010.

Richard Florida, The New Urban Crisis: How Our Cities Are Increasing Inequality, Deepening Segregation, and Failing the Middle Class—and What We Can Do About It. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

Brian Alexander, Glass House: The 1% Economy and the Shattering of the All-American Town. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2017.

Credits

Dan Holland currently teaches history at Duquesne University and the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work. A Pittsburgh native, Dan founded the Young Preservationists Association of Pittsburgh and has held leadership positions at local, regional, and national community reinvestment organizations. He specializes in modern American History, History of Pittsburgh, nonprofit management, historic preservation, and community reinvestment. Dan has taught World History, Western Civilization II, History of Sport, Sport & Global Capitalism, History of the 1960s, Debating the Purpose of American Government, and History of Pittsburgh at the University of Pittsburgh, Duquesne University, and Penn State New Kensington. Dan has also taught graduate courses at Université Jean Monnet in Saint-Étienne, France.