Short Teaching Module: Music and Decolonization in the Black Atlantic

Overview

The decades after World War II witnessed rapid decolonization of European empires and a dramatic increase in independence movements for colonized peoples. Historians focus on individual colonies and their transitions to independent countries in order to understand how and why decolonization happened when it did, but they also find it informative to explore the cultural connections made across different parts of empires in order to understand that anti-colonial movements operated at both local and global levels (and in the spaces in between). This module explores transnational histories of music, musicians, and their audiences in order to reveal some of the intricate networks colonized peoples from West Africa and the Caribbean created in their efforts to overthrow British colonial rule.

Essay

How can students begin to grasp the widespread influence of resistance to colonialism and the vast networks of communication and collaboration that colonized peoples created in their struggles for independence? One accessible cultural entry point is through music. In particular, historians use the tools of historical cultural analysis to focus on the music’s lyrics.

One example can be found in the British empire in West Africa and the Caribbean. This module focuses in particular on the connections between Akan highlife music from the Gold Coast Colony in British West Africa and calypso music from the colony of Trinidad & Tobago in the British West Indies. Advances in recording technology by the 1920s meant that music on records was widely available in many parts of the British empire, especially in urban areas where audiences interacted with and supported emerging nationalist leaders. Additionally, live performances or recorded music played at public and private gatherings expanded anti-colonial messages across urban and rural areas of the colonies. By contextualizing the lyrical content, historians generate a deeper understanding of the concerns voiced by colonized peoples. However, the music did not operate in a vacuum; it is best understood in the contexts of the broader networks of cultural production and transfer with which the music, its performers, and their audiences interacted across the Atlantic World. “Soundscape” is a useful term borrowed from music theory and ethnomusicology (among other disciplines) that can be used to encompass the vast networks in which sound was mediated by performers and their audiences and contributed to a collective framework through which colonized people across the Black Atlantic understood colonialism. The “soundscapes” could be heard at live public performances such as calypso competitions, public and private gatherings where calypso and highlife records were played, on radio broadcasts, and many other sonic contexts that contributed to an acoustic construction of knowledge about the experience of colonialism under British rule.

Through analyses of the numerous songs, historians can identify particular themes that were repeated across generations of cultural performances between the end of World War I and the independence period. Thematic analysis reveals the everyday grievances that colonized people had about their lives under British rule. Primary sources discussed in this module focus on economic struggles for Africans during the late colonial period in the Gold Coast Colony as it was transitioning to an independent Ghana during the 1950s. Economic concerns were common themes in calypso and highlife music throughout the first half of the twentieth century. West Africans and West Indians supported the British war effort in both world wars through their military service as well as agricultural and industrial production. However, those who served often found that they did not receive the pensions they had been promised and returned to the colonies to a lack of job opportunities. By the 1950s in Gold Coast Colony, Ghanaians were frustrated with lack of social mobility, so they agitated for self-determination in the belief that an independent Ghana would bring unity and better opportunities for work.

One of the major issues of the latter decades of colonialism was that British officials had introduced a cash crop economy focused on export of a select few agricultural products such as palm oil and cocoa to European markets, leaving Gold Coast to rely heavily on imports rather than maintaining a sustainable, diverse agricultural system to support its own population. This was a significant concern for nationalist leaders who envisioned a future for Ghana as a self-sustaining nation. A highlife song from the 1950s criticized the colonial economy and the lack of African control over the fruits of production. In his highlife titled “Cocoa,” the musician Joe Kelly sang in Akan about these concerns. (English translation is from Professor Kwadwo Osei-Nyame. Translation copies are held at Bokoor African Popular Music Archives Foundation in Accra, Ghana.)

Gold Coast money is taken abroad

Gold Coast money they take it abroad

Gold Coast money they use it to buy cloth

They use it to put up buildings

West Indian artists took a particular interest in the events in Ghana, demonstrating the significance of their transnational networks of cultural connections. Analysis of these kinds of broad connections across the soundscapes of the Black Atlantic reveals much about the collective nature of challenges to colonialism. As one of the first African nations to achieve independence, Ghana became a model for other African and also West Indian nations working toward their own self-determination. In London, West Indian and West African students, journalists, musicians, artists, and other intellectuals and their audiences exchanged ideas in social spaces as they helped create the language and framework for emerging nationalist movements. The connections between West African and West Indian artists in London and in the colonies help historians understand why, for example, the calypso song by the Trinidadian musician Lord Kitchener titled “Birth of Ghana” commemorating Ghana’s independence in 1957 came to be a soundtrack for the moment in the new nation’s history (see annotation). The Ghanaian highlife musician E.T. Mensah, who played music alongside West Indian musicians in London and listened to Lord Kitchener’s records, celebrated the country’s independence as well in his song “Ghana Freedom Highlife” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OUMbrs4aEsA). Today, the two songs are still played at independence day celebrations in Ghana and remain closely tied up with the memory of March 6, 1957.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Emmanuel Tettey Mensah. 1957. “Ghana Freedom Highlife.” Song can be heard on YouTube and other sites: See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OUMbrs4aEsA

Gocking, Roger S. 2005. The History of Ghana. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 86.

Lord Kitchener. 1957. “Birth of Ghana.” Song can be heard on YouTube and other sites: See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c-imEGXqHis

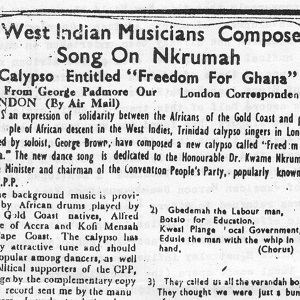

Padmore, George. Feb. 5, 1952. “West Indian Musicians Perform Song on Nkrumah” in The Ghanaian Morning Telegraph (London by Air Mail). Article copy archived at Bokoor African Popular Music Archive Foundation in Accra, Ghana. Original comes from Ghanaian Cape Coast Archives.

Credits

Daniel Kotin received his PhD from Washington State University in 2020. He currently teaches African and World History courses at Willamette University and Washington State University Vancouver. His research focuses on the lasting links between West African and Caribbean cultural histories. He is particularly interested in the impact of public and private cultural expressions upon collective memory and the generation of Black Nationalism in Britain’s Atlantic colonies during late colonialism and decolonization. His dissertation centered on the role of music, particularly Trinidad Calypso and Ghanaian Highlife, in this process.