Short Teaching Module: Borderland Migration and Communities in Twentieth-Century West Africa

Overview

Cross-border mobility has created borderland cultures and led to the development of vibrant communities that in some cases have stretched across several states. One example of this is West Africa, where during the colonial period, people continued to move between different colonies, ignoring the limits that colonial powers sought to put on their mobility. These networks continued after independence, and proved a resource for individuals, families, and communities during times of economic or political hardship, or of violence. To provide one example of these movements, this module uses population tables from the era of World War I, when people fled across colonial boundaries to avoid military conscription, to trace patterns in their migrations. Population figures, combined with reports of the reasons that people migrated, are one way to track the movement of people at specific historical moments. However, other histories of these movements are contained within oral traditions and histories maintained and passed on by family members themselves. In many communities in West Africa to this day, people remember their parents and grandparents fleeing military conscription and moving into new colonies, but maintaining their familial and social ties across borders

Essay

People often think about borders from the perspective of their own nation/state. In the United States, for example, we often discuss the U.S.-Mexico border from the standpoint of how that border affects those living in the U.S., but borderlands—the larger zone surrounding the border—are dynamic spaces where both sides of the border shape one another. In most border zones globally, people have sociocultural and economic connections that span multiple countries and create integrated areas where people live, work, and socialize. Borders provide incentives for people to cross, either permanently or temporarily, to take advantage of favorable socioeconomic and political conditions. And of course, borders have also served to divide people into residents and citizens of different states, at times enforcing those boundaries through varying levels of restrictions. Historically, cross-border mobility has created borderland cultures and led to the development of vibrant communities that in some cases have stretched across several states.

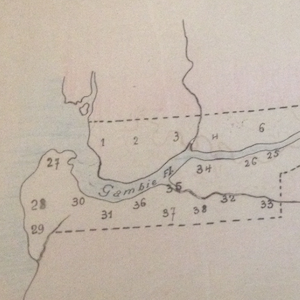

One example of these interconnected cross-border networks comes from areas in West Africa of eastern Gambia, southern Senegal, eastern Guinea-Bissau, and northwestern Guinea. These areas saw substantial migration before the drawing of colonial boundaries in the 1880s, which divided the region into the French colonies of Senegal and Guinea, the British colony of Gambia, and Portuguese Guinea (today Guinea-Bissau). Throughout the colonial period, people continued to move between different colonies, ignoring the limits that colonial powers sought to put on their mobility. Many people fled across colonial boundaries to avoid military conscription, most notably during World War I, as the primary sources in this module will demonstrate. During the war, tens of thousands of people left the French colony of Senegal for neighboring British Gambia and Portuguese Guinea-Bissau.

People moved for a variety of reasons, but whatever the reason, these movements created a cross-border space. The example of Amadú Bailo Djaló, born in eastern Guinea-Bissau in 1940, is instructive. Djaló’s parents came from neighboring Guinea (then French Guinea), and as a child, he and his brother began to trade between Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, and further south into Sierra Leone. Beginning in 1959, Djaló and his cousin began to travel between Guinea-Bissau and Senegal to participate in clandestine trade. Two years later, Djaló opened a market stall in the eastern Guinea-Bissau city of Bafatá, where he sold items from several neighboring colonies/states (Djaló 2010).

These networks continued after independence, and proved a resource for individuals, families, and communities during times of economic or political hardship, or of violence. During Guinea-Bissau’s war for independence (1963–1974), more than 100,000 people fled the country for neighboring Senegal and Guinea. Some of these migrants assisted the liberation movement from their new countries, while others simply settled in communities where they already had family. And throughout the 1960s and 1970s in Guinea, hundreds of thousands left the country due to economic hardship and political persecution under President Sékou Touré’s “modernization” campaigns. Many of these individuals and families followed previous migratory routes and settled in villages, towns, and cities in Senegal, Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau, with some migrating as far as the Senegalese capital of Dakar.

Borderland networks allowed those living in these regions to live in two parallel spaces simultaneously: one of individual, bounded nation-states, separated by governments and colonial/national cultures, and a second, cross-border space characterized by mobility, fluidity, and connection. People moved in between these spaces when helpful or necessary, creating a challenge to integrating borderland regions into the nation after independence. Most of those living in this region were Fulbe people who spoke the region’s lingua franca, Pulaar. Because of their ethnolinguistic connections, residents of one side of the border were easily able to cross the border, integrate into a new community, and claim to their government that they had never lived anywhere else. The scale of these movements was so large that by 1968, one-third of people living in the Senegalese region of Kolda were of Guinean Fulbe descent.

Cross-border migrants were often frequently criticized by their governments, but they continued to move despite public condemnation and efforts to restrict mobility. In a 1976 speech, the Guinean President Sékou Touré compared migrant seasonal farmers to thieves, prostitutes, and alcoholics, all of whom needed saving by the Guinean state. He specifically accused those who went to Senegal of going “to humiliate the Nation” (Touré 1978: 186). However, these migrations continued a long tradition of mobility as a tool to escape state control. As one French report wrote in 1918 during the period of military conscription for World War I, mobility limited their ability to enact legislation because of “the possibility of evading our action by moving a few kilometers” (Archives Nationales du Sénégal 2F10, “Déserters et insoumis,” Nov. 19, 1918). Given the relatively recent drawing of colonial boundaries, many of which were only delineated around the beginning of the 20th century, most communities did not accept these borders as legitimate dividers. The general disregard for the border was furthered by the inability of colonial governments to put in place firm controls to restrict movement, and the minimal investment in most borderland regions. These dynamics were not unique to West African borderlands but exist globally in many former colonies.

Colonial and postcolonial borderlands allow for an understanding not just of the dynamics of border control, but they also provide a clear window for creating transnational spaces outside of national boundaries. States were not and are not bounded containers, with borders separating demarcated territories. Many living in borderlands have created their own parallel geographies that offer an alternative to national spaces, which can be particularly opportune at moments of crisis. These spaces also lead to questions about the meaning of national identity and belonging. What does it mean to be a citizen of a specific state, when the boundary between those in Senegal and Gambia, for example, is quite porous? How have states worked to create national identities, and what limits to these identities do borderland spaces reveal? Of course, governments have often sought to inculcate a sense of national identity through a variety of means, ranging from educational systems to national sports teams to national anthems. Borderlands, especially those in former colonies, often show the cracks in these attempts to create national unity, and the difficulty in manipulating and shaping previous identities.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Amadú Bailo Djaló, Guineense, comando, português (Lisbon: Associação de Comandos, 2010).

Ahmed Sékou Touré, “Enterrer le racism peulh: discours au meeting d’information du Comité Central le 22 aôut 1976,” in Touré, Unité Nationale, Révolution Démocratique Africaine no. 98, 3rd edition (Conakry: Imprimerie Nationale “Patrice Lumumba,” 1978 [1976]) ANS 2F10, Archives Nationales du Sénégal 2F10,

“Déserters et insoumis,” Administrateur de France en Guinée Portugaise au Gouverneur Général de l’Afrique Occidentale Française, November 19, 1918.

Credits

David Glovsky is an Assistant Professor of History at Boston University, where he teaches and researches African history. His research focuses on the history of cross-border Fulbe communities between Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, and Guinea. He has published articles on the religious, social, economic, and military history of West African borderlands.