Primer: Gender in World History

Overview

Gender history developed in the 1980s out of women’s history, when historians familiar with studying women increasingly began to discuss the ways in which systems of sexual differentiation affected both women and men. Historians interested in this new perspective asserted that gender was an appropriate category of analysis when looking at all historical developments, not simply those involving women or the family. Gender became a primary focus of many historical studies – and women’s history continued as its own field – and also a method of analysis for all kinds of topics. Gender historians have paid particular attention to certain topics in world history, including the study of studies of movements for women’s rights and rights for LGBTQ+ people, migration, colonialism and imperialism, and the diversity understandings of gender and sexuality around the world.

Essay

Gender history developed out of women’s history, which itself was a product of the feminist movement that began in the 1960s, for which one goal was to understand more about the lives of women in the past. Historians familiar with studying women increasingly began to discuss the ways in which systems of sexual differentiation affected both women and men, and by the early 1980s to use the word “gender” to describe these social and cultural systems. “Gender” spread in other academic fields as well, and then into ordinary speech, becoming the accepted replacement for “sex” in many common phrases – “gender roles,” “gender distinctions,” and so on.

Historians interested in this new perspective asserted that gender was an appropriate category of analysis when looking at all historical developments, not simply those involving women or the family. Every political, intellectual, religious, economic, social, and even military change had an impact on the actions and roles of men and women, and, conversely, a culture’s gender structures influenced every other structure or development. People’s notions of gender shaped not only the way they thought about men and women, but the way they thought about their society in general. Hierarchies in other realms of life were often expressed in terms of gender, with dominant individuals or groups described in masculine terms and dependent ones in feminine. These ideas in turn affected the way people acted, though explicit and symbolic ideas of gender could also conflict with the way men and women chose or were forced to operate in the world.

Gender became a primary focus of many historical studies – and women’s history continued as its own field – and also a method of analysis for all kinds of topics. There was resistance from more traditional historians, but conferences, articles, books, scholarly journals, courses, and programs in women’s and gender history affirmed the field was here to stay. These are unevenly distributed, as the amount of research on and teaching in English-speaking areas outweighs that of the rest of the world, but there are signs that this imbalance is changing somewhat.

Women’s and gender history developed at roughly the same time as world and global history, but until about 2000, there was little connection between them. World/global history tended to focus on large-scale political and economic processes carried out by governments and commercial elites. Most of the people involved were men, but how gender shaped their experience was not evaluated, as the primary emphasis was on material rather than cultural factors. Historians of gender have tended to have a narrower range of focus, choosing to study individuals, families, circles of friends, and other small groups, and have been worried that these would get lost in narratives that emphasize impersonal processes. Although many have studied economic developments and political movements, they have also paid more attention to cultural issues, representation, and meaning than have most world historians.

This lack of intersection is beginning to change, however, particularly on certain topics. These include studies of movements for women’s rights and rights for LGBTQ+ people; recent scholarship has made clear that these movements were (and are) transnational, though with different emphases in different parts of the world as they connected with other social and political issues, such as nationalism and anti-imperialism. Comparative and global studies are evaluating similarities and differences between feminism and other social justice movements in West and East, North and South, and examining what happens when ideas, institutions, and individuals cross borders.

Migration itself is another world history topic in which there are growing numbers of studies that integrate gender. Although in some earlier eras the large majority of migrants were men, today approximately half of all long-distance migrants are female, with women’s migration patterns sometimes similar to those of men but sometimes quite different. Scholars examine the “transnational” character of migrants’ lives, in which women and men physically move back and forth and culturally and socially create and maintain links across borders. They also discuss ways in which gendered migration shaped (and continues to shape) the economies, societies, and polities through and across which people moved.

The history of colonialism and imperialism is a third area of fruitful intersection. Both men and women were agents in imperial projects, and colonial powers shaped cultural constructions of masculinity and femininity, in both colonized areas and the metropole. Recent works explore the ways that imperial powers controlled families and sexuality, developed racialized notions of gender relations and difference, and established policies of inclusion and exclusion. They also examine people who challenged or ignored restrictions and boundaries through intermarriage and other types of sexual and intimate relationships, which facilitated cultural exchange, mixing, and hybridity. These occurred especially in colonies or border regions that were both political and gender frontiers.

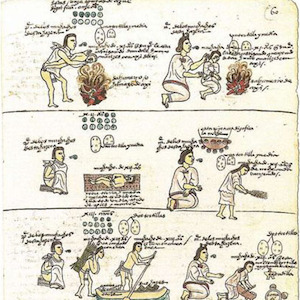

Gender is often thought of as a dichotomy, a male/female binary linked to other binaries, including light/dark, strong/weak, nature/culture, public/private, inner/outer, and order/disorder. But today we increasingly recognize that the categories “woman” and “man” are socially created, and that gender is more complex than it at first seems. This more complicated notion of gender might seem very modern—or even “post-modern”—but historians and anthropologists are increasingly demonstrating that diverse and fluid understandings of gender and sexuality have a long past, a fourth topic that brings together world history and gender history. They have found that many of the world’s cultures had (and sometimes continue to have) a third or even a fourth and fifth gender, often with specialized religious or ceremonial roles. Not only in the present is gender “performative,” that is, a role that can be taken on or changed at will, but it was so at many points in the past, as individuals “did gender” and conformed to, combined, or challenged gender roles and identities. Such historical examples are often used by people within the LGBTQ+ community to demonstrate both the extent of nondichotomous understandings and the socially constructed and historically variable nature of all notions of gender and sexual difference.

Gender analysis has been used for many other common topics of world history as well, including the domestication of plants and animals, the growth of cities and states, the spread of world religions, slavery, rebellions and revolutions, diplomacy, labor and leisure, industrialization, and modernization. Scholars examine the ways that gender combined with race, class, sexual orientation, religion, and other factors to create interlocking systems of oppression, an idea the critical race theorist and feminist legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw called “intersectionality,” which, like gender, has moved from academia into activism and ordinary speech. The concept of intersectionality has also become increasingly dynamic and global, analyzing (and critiquing) structures of power and oppression that arise from a variety of situations.

Over the last thirty years, scholars have shown that there is no aspect of human existence that is untouched by gender. From the earliest human cultures until today, the process of defining societies, ruling them, settling them, and building them has been carried out by women, men, and people who understood themselves to be another gender entirely, but always according to gendered principles.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Further Reading

Collins, Patricia Hill and Sirma Bilge. Intersectionality. London: Polity, 2016.

Kent, Susan Kingsley. Gender: A World History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Meade, Teresa A. and Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks, eds. A Companion to Global Gender History. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd ed. 2021.

Rose, Sonya O. What Is Gender History? London: Polity, 2010.

Stearns, Peter. Gender in World History. London: Routledge, 3rd ed. 2015.

Willoughby, Urmi Engineer and Merry E. Wiesner-Hanks. A Primer for Teaching Women, Gender, and Sexuality in World History. Series: Design Principles for Teaching History. Series Editor: Antoinette Burton. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018.

Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. Gender in History: Global Perspectives. London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd ed. 2011, 3rd ed. 2022.

Credits

Merry Wiesner-Hanks is Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. She is the long-time senior editor of the Sixteenth Century Journal, an editor of the Journal of Global History, and the editor-in-chief of the nine-volume Cambridge World History (2015). She is an author or editor of more than thirty books and nearly 100 articles that have appeared in English, German, French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Greek, Chinese, Turkish, and Korean.