Long Teaching Module: Doña Marina, Cortés' Translator

Overview

What is the language of conquest? What language do people speak when they battle for land and autonomy, or meet to negotiate? During the conquest of Mexico, Spanish and Nahuatl—the mother tongues of the conquistadors and the Mexica—grew newly powerful. Maya, Otomí and hundreds of other languages were spoken in Mesoamerica in the early 16th century. Yet Hernán Cortés understood only Spanish. Whenever he met with indigenous allies or confronted enemies, whenever he solicited food for his men or sought directions across mountainous terrain, he relied upon perilous and delicate acts of translation. In the early days, Spanish was translated to Maya and then to Nahuatl, later it would be Nahuatl to Spanish or the reverse. From 1519 to 1526, Cortés trusted in the translations and counsel of a woman, and she traveled across Mexico by his side. Her name was doña Marina in Spanish, Malintzin in Nahuatl. Today she is often Malinche.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, activities, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, and essay prompts relating to the twelve primary sources.

Essay

Doña Marina’s Biography

In 1519, shortly after Cortés arrived on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, this young woman was one of 20 slaves offered the Spanish conquistadors by a Maya lord. Baptized Marina, she distinguished herself in extraordinary ways, becoming instrumental to the Spaniards’ logistical ambitions and political endeavors. She served as translator, negotiator and cultural mediator. She was also Cortés’s concubine and gave birth to their son, Martín. In 1524, she was married to the conquistador Juan de Jaramillo, and again became a mother—this time of a daughter, María.

The daily patterns of doña Marina’s life cannot be well documented. When doña Marina or Malintzin was a child growing up near today's Veracruz, her people were attacked by the Aztecs, and she ended up being sold into slavery in Maya territory. And for all the respect the title ‘doña’ and the reverential suffix ‘–tzin’ (in Malintzin) imply, she endured difficult days. She survived the massacre of indigenous people at Cholula, the conquest of Tenochtitlan, a grueling march with Cortés and his men to Honduras and back. She witnessed the deaths of hundreds and bore the children of two Spanish men. Whatever her ability to negotiate cultural differences, she died a young woman—in, or before 1527—and probably not more than 25 years old.

16th-Century Sources—Doña Marina and Malintzin

As with so many women from the past, none of doña Marina’s actual words have survived, although descriptions written by conquistadors who knew and relied upon her stress her linguistic abilities. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who marched with Cortés, claims she was beautiful and intelligent, she could speak Nahuatl and Maya. Without her, he says, the Spaniards could not have understood the language of Mexico. Díaz’s account is the most generous of any conquistador, but it was written decades after the conquest—his eyewitness history filtered through memory. In contrast, the conquistador who knew this woman best, Hernán Cortés, mentions doña Marina just twice in his letters to the King of Spain. Her appearance in the Second Letter has become the most famous. Here he describes her not by name but as “la lengua…que es una India desta tierra” (the tongue, the translator…who is an Indian woman of this land).

Indigenous sources from the 16th century depict Malintzin through her deeds. The Florentine Codex, one of the most extensive Nahuatl descriptions of the conquest, hints at Malintzin’s bravery—as when she speaks from a palace rooftop, ordering food brought to the Spaniards, or at other times gold. In visual images, Malintzin appears as a well-dressed young woman, often standing between men who communicate and negotiate via her multilingual skills. Scenes from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala, now just fragments from a larger set of images, draw upon preconquest painting techniques and conventions. Like Malintzin herself, the Lienzo straddles a world of indigenous, preconquest practice and European intervention. Indigenous paintings of Malintzin from the 16th century do not bear their maker’s signature, and many post-date her death. Whether she would have approved of any of these images, we cannot say. Because so few women surface in indigenous representations of the conquest, her repeated appearance confirms that Nahuas, and not only Spaniards, recognized her importance.

Recent Sources—Malinche, Doña Marina, Malintzin

Since the 16th century, doña Marina’s reputation has remained neither static nor settled. Some have condemned her as traitor and collaborator because she aided the Spaniards, quickening the demise of indigenous Mexico and the rise of foreign rule. For others, she was the consummate strategist. Passed to Cortés as a slave and forced to travel at his side, what were her options for survival if she did not translate, if she would not bear his child? And because she bore Cortés a son, doña Marina has been deemed the mother of the first Mexican mestizo. Their child could not have been the first, but her union with Cortés—literally and metaphorically—inextricably binds her to the history of mestizaje.

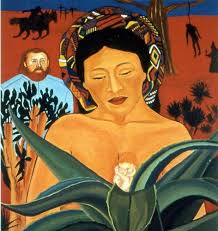

Many Mexican texts and images speak to these conflicted understandings. Two well-known works from the mid-20th century include Antonio Ruiz’s painting, El sueño de la Malinche (“The Dream of Malinche”) and Octavio Paz’s essay, “The Sons of Malinche,” in which he castigates doña Marina as the violated mother of the Mexican nation.

More recently, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Chicana writers, artists, and activists began rethinking the story of Malinche. In 16th-century sources, they found neither victim nor traitor but the strength of a survivor. Malinche did not choose her destiny, but neither did she crumble in the face of adversity. Poems by Adaljiza Sosa-Ridell and Carmen Tafolla explore Malinche’s fate and her abilities to negotiate difficult and competing cultural demands. Their narratives also grapple with the violence of colonization—in history, in Mexico and in the United States. The histories they tell are histories of indigenous and Chicana women, but also of shifting political borders.

The violence of Spanish conquest and the quandaries it unleashed persist in the present. We are reminded of this when comparing two contemporary works of art: La Malinche, by Santa Barraza and Jimmie Durham’s Malinche. The former, which depicts the beautiful, life-giving Malintzin, is a tiny image crafted on metal, it evokes ex-voto and other devotional images from Mexico. While it does not deny the horrors of Christian conquest, it paints a world where beauty and violence coexist. In contrast, Jimmie Durham’s sculpture stresses the darker underside of Malinche’s history. There is nothing redemptive in Durham’s vision—Malinche may wear jewelry and feathers in her hair, but no beauty surfaces, no hope arises.

Is either of these images less “true” than the doña Marina of Díaz del Castillo’s nostalgic recollections or the Malintzin described by Nahua scribes in the Florentine Codex? This is one question posed by this collection of sources. A second question they prompt: does the history of an individual’s life have an end? In suggesting how the life of one woman took form and then was reshaped across the 20th century, in charting the afterlife of Malinche, these sources imply that history is most vibrant when it does not seek to understand individuals at just one moment in the past. To understand the language of conquest, then, it might be necessary to explore how the living remember the deceased, and how ancient accounts transfix the present.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

As a collection, these works describe the shifting meaning of the historical figure known today by three names: doña Marina, Malintzin, Malinche. The source documents range widely across time and media, from the 16th to the 20th century—from chronicle to poetry, essay to sculpture. This collection therefore begs the methodological question: what lends historical authority to an image or written text? For instance, how, or why, can a painting become a viable historical source? No writing or visual image is known today that records doña Marina’s own words or thoughts. It will therefore be useful to ask what perspective on doña Marina each of these sources creates. Reading comparatively, one can look across a selection of these sources with an eye to the events and vocabulary they underscore. Just as one might read texts for their particular emphases or omissions, images can be read in terms of composition and descriptive language (where Malintzin appears, what she wears, what environment or setting she occupies, with what degree of care or inattention each figure is rendered). The 16th-century sources offer an opportunity to weigh distinct ways of representing the Spanish conquest of Mexico and its participants. The 20th-century materials invite further reflection on the legacy of this conquest, the Chicano movement, feminist expression in the United States, and border histories. Attending to the nuances of visual and verbal language in recent sources—“code-switching,” from English to Spanish, or the materials and compositions used to portray Malinche—opens conversations about the way a historical figure accrues or sheds meaning over time.

Discussion questions:

- Consider how 16th-century sources describe doña Marina, Malintzin. What do their similarities (and differences) suggest about her historical role and reputation in the first decades after the Spanish conquest?

- In what ways do the perspectives expressed in 20th-century images of and writings about Malinche differ from those of the 16th century? What do these differences suggest about historical “accuracy”: whose perspectives on this woman are most binding—those of the conquistadors who knew her, or 20th-century feminists who see her as a role model, or painters and sculptors who render her in visual terms?

Lesson Plan

Doña Marina/Malinche: Traitor, Victim, or Survivor?

Time Estimate

Three 50-minute class periods.

Objectives

After completing this lesson, students will be able to:

- read and analyze a variety of sources, both primary and secondary, including poetry and examples of visual art.

- determine the point of view of the creators of the sources, evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of each.

- interpret and evaluate the sources, especially the role of women as seen in these sources.

- reach a possible conclusion as to the accuracy of the portrayal of Malinche by the various sources.

- determine what other sources would be useful (e.g., a map showing the location of those who hated the Aztecs and were willing to join the Spaniards to fight their enemy).

- consider how the interpretation of historical information changes over time.

Materials

- Sufficient copies of the following two excerpts for the hook:

- The New York Times, March 1997

- El Ojo del Lago, December 1997

- The following sources found in the Primary Sources folder on this page:

- Source 3: Painting, Mexican Manuscript

- Source 4: Painting, Florentine Codex

- Source 7: Painting, The Dream of Malinche

- Source 11: Sculpture, Durham

- Source 1: Letter, Hernan Cortés

- Source 2: Personal Account, Bernal Diaz del Castillo

- Source 5: Nonfiction, Florentine Codex (Spanish)

- Source 6: Nonfiction, Florentine Codex (Nahuatl)

- Source 8: Nonfiction, Octavio Paz

- Source 9: Poem, Como Duele

- Source 10: Poem, La Malinche

- Sufficient copies of Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Images

- Sufficient copies of Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts

- Blackboard and chalk or whiteboard and markers

- Paper and colored pencils for less advanced students

Strategies

-

Hook: Hand out and read the two excerpts. Have students discuss what it means to be a traitor, a victim, or a survivor. On the board, create three columns, one for each term. Then list the points made by the students beneath the appropriate term. Lead a discussion on the types of sources needed to make a reasoned, rational judgment. Discuss what students know about the Conquest of Mexico and the role of women in that region during the 16th century. Read the overview of Doña Marina, Cortés's Translator above.

-

Images: Create a chart that has three columns: Traitor-Victim-Neither. This chart will help the students decide between different perceptions of Doña Marina/Malinche and will assist them later in the lesson when a trial is held based on the sources.

Direct students to the following images in Primary Source Folder: Source 3: Painting, Mexican Manuscript, Source 4: Painting, Florentine Codex, Source 7: Painting, The Dream of Malinche, Source 11: Sculpture, Durham Distribute four copies of Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Images to each student (or use a different primary source analysis sheet of your choosing). Divide the class into two groups. Have students examine these sources carefully, noting that two are from the 16th century and two are from the 20th century. As the documents are read and evaluated, each group decides how valid it thinks a document is, what image is projected of Doña Marina, what changes occurred to her image over time. Students should decide which role is suggested by each source, (e.g., the personal account of Diaz del Castillo suggests reasons to believe that Doña Marina was a victim, while the painting from the Florentine Codex implies that she was a collaborator.) Students should complete a worksheet for each source.

Students should also consider the following questions:

- What can we infer about the painters? (What does indigenous mean? Does the name Ruiz suggest anything about the painter's background?)

- What can we infer about the painters' point of view?

- What does each painting tell us about Doña Marina?

- What details suggest her role?

- What similarities or differences are there between the works of the two different time periods?

- What does this tell us about the interpretation of history?

- How valid is each image as a source of historical knowledge?

Students should try to decide if the paintings portray Doña Marina as a traitor or a victim, using the criteria listed on the board to help make decisions. Note reasons for the choices made.

-

Texts: Direct students to the following sources in the Primary Sources folder on this page: Source 1: Letter, Hernan Cortés, Source 2: Personal Account, Bernal Diaz del Castillo. Distribute two copies of Primary Source Analysis Worksheet: Texts to each student. Have students read the sources documents silently. Complete a worksheet for each of these primary sources.

Students should also consider the following questions:

- Who are the authors?

- When were they written?

- How are they alike?

- How are they different?

- Both men knew Doña Marina. Circle the words used by each to describe her. Why would Cortés be so abrupt in his description of a woman he knew intimately? Why is Diaz del Castillo's account more detailed? How valid is each man's assessment of Doña Marina?

- What are the strengths/weaknesses of each account?

Where would each student place these two documents on the Traitor-Victim-Neither chart? Why?

-

Texts: Direct students to the following two sources: Source 5: Nonfiction, Florentine Codex (Spanish), Source 6: Nonfiction, Florentine Codex (Nahuatl). Students read aloud the two versions, one in Spanish, one in Nahuatl, of the Spanish entry into a private home and what happened. Note the author and date of the original source and the translators and source for the later edition. Compare the two (Spanish and Nahuatl) versions of the event.

Students should also consider the following questions:

- What is different in them? Write specific examples of these differences. What does this tell us about translations of sources?

- Look back in the Images sources and find the one that is also from the Florentine Codex. How well does the painting reinforce the account or does it?

- What do we learn from the three examples taken from the Florentine Codex about the role of women?

- Would Doña Marina be a typical example of women of her time and place?

- Where might these two sources go on Traitor-Victim-Neither chart? Why?

- Homework: Have students read Source 8: Nonfiction, Octavio Paz. This is an essay by Octavio Paz to be read and evaluated at home. In addition to the worksheet activity, students should keep a running list of questions raised by their reading, and they should look up unfamiliar terms. The essay is lengthy, has sophisticated language and complex concepts. The reading will take a considerable amount of time and thought. Some questions to consider as the students read the essay, or for discussion on the following day, are:

- What is meant by Mexican hermeticism?

- How do Europeans characterize Mexican/Mexico?

- How does Paz characterize the Mexican work ethic? the servant mentality?

- What "vestiges of past realities" create struggles for Mexicans?

- Who does Paz define as la chingada? hijos de la chingada?

- What are some of the many meanings of chingar?

- What is meant by the phrase, "I am your father."?

- What vision of God does the Mexican venerate? Why?

- Who is Chauhtemoc?

- Who is the symbol of the "violated Mother?" Why?

- What does the adjective malinchista mean?

- What is meant by the frequent shout, "Viva Mexico, hijos de la chingada!"?

- What does the essay tell us about the role of women in contemporary (1985)

Mexican life? - What does Paz tell us about Malinche (Doña Marina)?

- What does this document add to the Traitor-Victim-Neither chart and where should it go?

- Discussion: The homework assignment of the Paz document should be thoroughly discussed. Why is this essay "now a touchstone and point of departure for revisionist work on Malinche, particularly by feminist, Chicana writers, artists and activists?” What is there in Paz's interpretation that would lend itself to revision?

- Poetry: Direct students to Source 9: Poem, Como Duele and Source 10: Poem, La Malinche. Have students read these aloud and discuss the meaning of each. Who wrote the poems and when? Define the concept la raza (the people). Discuss other language as needed. What phrases are used by Tafolla to characterize Malinche? What was Malinche's fate according to Sosa-Riddell? What technique does Sosa-Riddell use to weave the story of both indigenous and Chicana people? What do we learn about the image/role of women from the poems?

- Trial of Doña Marina: The two groups previously selected will work together in class to prepare for a treason trial of Doña Marina. One group will select the Defendant, Defense Attorney, and any witnesses needed for the case. The other group will select the Prosecutor and such witnesses needed for the case. (Witnesses could be Montezuma, Cortés, Aztec persons, neighboring indigenous people, a priest, a Spanish soldier etc. Their testimony must be based on information from the sources. The number of witnesses is optional.) The two groups work to prepare the presentation—Doña Marina's opening statement is NOT the work of one student, but all in the defense group will decide what she is to say. This is true of every speaking role. The jury will have an equal number selected from each group and should be encouraged to render a verdict based on the presentation of the sources. If this fails to bring in a verdict, the "judge" (teacher) renders a decision.

Students should select from the documents in the chart those arguments which best fit their charters. In their statements, students should explain why the sources used are valid ones (e.g., eyewitness account, and in the concluding summation, the weakness of the opponents' arguments should be noted [e.g., too much time elapsed]).

The trial begins with the judge addressing Doña Marina . . . is she guilty or not guilty of treason?

Doña Marina reads her opening statement. The prosecution delivers an opening statement of intent to prove guilt. The defense delivers an opening statement of intent to prove victimization, not treason. Prosecution calls witnesses. Defense calls witnesses. Each side has a summation. Jury deliberates and reaches a verdict. Discussion by the entire class follows to determine how the image of Malinche changed over time. How were the contemporary sources different from the ones from the 16th century? Which sources do the students consider the most effective or “correct?” Which voices are the most believable, those from the 16th or those from the 20th century?

Differentiation

Advanced Students: Have students read from the bibliography (below) about this fascinating woman and the various interpretations of her historic role. What additional sources would be helpful? Advanced students will also take a day to write the DBQ.

Less Advanced Students: Have students create a drawing of Malinche when they have completed activity 2. Omit activity 5, homework. Compile the worksheets and create an outline for these students to use while writing the DBQ.

Document Based Question

Document Based Question (Suggested writing time: 40 minutes)

Directions: The following question is based on the documents included in this module. This question is designed to test your ability to work with and understand historical documents. Write an essay that:

- Has a relevant thesis and supports that thesis with evidence from the documents.

- Uses all or all but one of the documents.

- Analyzes the documents by grouping them in as many appropriate ways as possible. Does not simply summarize the documents individually.

- Takes into account both the sources of the documents and the authors' points of view.

You may refer to relevant historical information not mentioned in the documents.

Question: Using the documents and images from the Doña Marina: Cortés's Translator module

- Describe the role and reputation of Doña Marina that emerges from an analysis of the early (16th century) sources. Were these eyewitness accounts? Did the author/artist know Doña Marina personally? Describe the changes to Doña Marina's role and reputation evident in the later (20th century) sources. Why can history be seen differently over time?

- Evaluate Doña Marina’s status as traitor, victim, or survivor. Express a thoughtful opinion, and in doing so, evaluate the validity of the sources. Which sources seem the most reasonable to use to draw conclusions? Why are there stark differences in the perception of Doña Marina/La Malinche over time? What can these sources really tell us about the lifestyle of women in 16th century Mexico?

Be sure to analyze point of view in at least three documents.

What additional sources, types of documents, or information would you need to have a more complete view of this topic?

Bibliography

Credits

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following institutions for primary sources:

Dr. Blair Sullivan, UCLA Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies

Luisa Barrios, Galeria de Arte Mexicana

About the Author

Dana Leibsohn is Associate Professor of Art History and Director of the Latin American and Latino/a Studies Program at Smith College. Her research interests involve indigenous visual culture in colonial Latin America, with an emphasis on maps and modes of literacy, and she has received recognition and grants from the J. Paul Getty Trust, the National Gallery of Art, and the National Endowment for the Humanities. In 2004 she was awarded the Conference of Latin American History Best Article prize for “Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America.” She is currently working on a multimedia project entitled Vistas: Colonial Latin American Visual Culture: 1520-1820.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Harriett Lillich has extensive experience developing and implementing the Advanced Placement World History and Advanced Placement European History examinations. She received her AB and MA from the University of Alabama and taught for 36 years in Mobile, Alabama—first at Murphy High School and then at UMS-Wright Preparatory School. She has served as Faculty Consultant for the AP European History examination and was on the task force that recommended the implementation of the AP World History exam. She has written test questions for the SATII World Cultures exam, reviews for AP Central Teacher Resources, and AP European History Workshop Materials for 2004-05 (Special Topic: Teaching with Primary Sources). She has also received a Fulbright for study in The Netherlands and a Council for Basic Education grant to read “Imperial Russia: Peter the Great to the 1917 Revolution.”

This teaching module was originally developed for the Women in World History project.