Source Collection: Slavery and the Haitian Revolution

Overview

Since the revolutionaries explicitly proclaimed liberty as their highest ideal, slavery was bound to come into question during the French Revolution. Even before 1789 critics had attacked the slave trade and slavery in the colonies. France had several colonies in the Caribbean in which slavery supported a plantation economy that produced sugar, coffee, and cotton. The most important of these colonies was Saint Domingue (later Haiti), which had 500,000 slaves, 32,000 whites, and 28,000 free blacks (which included both blacks and mulattos). Some free blacks owned slaves; in fact, the free blacks owned one-third of the plantation property and one-quarter of the slaves in Saint Domingue, though they could not hold public office or practice many professions (medicine, for example).

This Source Collection includes an informational essay and 41 primary sources.

Essay

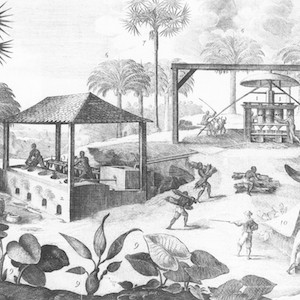

The slave system in the colonies was regulated by a series of royal edicts, the most important of which was promulgated by Louis XIV in 1685. Taken together, the edicts constituted the Code noir, or slave code. This code prescribed a harsh regime of penalties for slaves who resisted their captivity, especially if they tried to harm their masters in any way. Saint Domingue provided extraordinary sources of wealth to the French. To protect their investments, French slaveholders had to learn at least a minimal amount about their slaves. One of the most astute commentators, Médéric-Louis-Elie Moreau de Saint-Méry, wrote a massive two-volume work on life in Saint Domingue in the 1780s. He described many of the features of slave life that worried slaveholders, including voodoo imported from Africa, the presence of many people of mixed race (mulattos), the threat of slaves becoming Maroons (runaways), and the intense fear among slaveholders that their slaves would try to poison them. After the French Revolution broke out, planters looked back on pre-1789 conditions, trying to understand how slavery might have been better organized. Their observations provide yet another contemporary perspective on the plantation and slave system.

The Caribbean colonies were quick to respond to the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789. The white planters of Saint Domingue sent delegates to France to demand representation at the new National Assembly, as did the mulattos. Several prominent deputies in the National Assembly belonged to the Society of the Friends of Blacks, which put forth proposals for the abolition of the slave trade and the amelioration of the lot of slaves in the colonies. When these proposals fell on deaf ears, some deputies sympathetic to blacks turned to arguing that full civil and political rights should be granted to free blacks in the colonies. Before long, radical journalists in Paris began to take up the cause of black slaves, pushing for the abolition of slavery, or at least for a more positive view of the Africans. The pioneering feminist and playwright, Olympe de Gouges, also wrote a pamphlet challenging the colonial pro-slavery lobby to improve the lot of the blacks.

As the agitation in favor of granting rights to free blacks and abolishing the slave trade gathered steam, the colonies became filled with uncertainty and expectations began rising, especially among the free blacks and mulattos. In response, the white planters mounted their own counterattack and even contemplated demanding independence from France. Less is known about the views of the slaves because hardly any of them could read or write, but the royal governor of Saint Domingue expressed concern about the effects of the Revolution on the colony's slaves. In October 1789 he reported that the slaves considered the new revolutionary cockade (a decoration made up of red, white, and blue ribbons worn by supporters of the Revolution) a "signal of the manumission of the whites . . . the blacks all share an idea that struck them spontaneously: that the white slaves kill their masters and now free they govern themselves and regain possession of the land." In other words, the black slaves hoped to follow in the footsteps of their white predecessors, freeing themselves, killing their masters, and taking over the land.

Most deputies feared the effects of the loss of commerce that would result from either the abolition of slavery or the elimination of the slave trade. Fabulous wealth depended on slavery, as did shipbuilding, sugar-refining, and a host of subsidiary industries. Slaveowners and shippers did not intend to give up their prospects without a fight. The U.S. refusal to give up slavery or the slave trade provided added ammunition to support their position.

To quiet the unrest among the powerful white planters, especially in Saint Domingue, the colonial committee of the National Assembly proposed in March 1790 to exempt the colonies from the constitution and to prosecute anyone who attempted to spark uprisings against the slave system. But the steadily increasing agitation threatened the efforts of the National Assembly to mollify the white planters and keep a lid on racial tensions. The March 1790 decree said nothing about the political rights of free blacks, who continued to press their demands both in Paris and back home, but to no avail. In October 1790, 350 mulattos rebelled in Saint Domingue. French army troops cooperated with local planter militias to disperse and arrest them. In February 1791 the mulatto leaders, including James Ogé, were publicly executed. Nevertheless, on 15 May 1791, under renewed pressure from the abbé Grégoire and others, the National Assembly granted political rights to all free blacks and mulattos who were born of free mothers and fathers. Though this proviso limited rights to a few hundred free blacks, the white colonists furiously pledged to resist the application of the law.

Just a few months later, on 22 August 1791, the slaves of Saint Domingue rose up in rebellion, initiating what was to become over the next several years the first successful slave revolt in history. In response, the National Assembly rescinded the rights of free blacks and mulattos on 24 September 1791, prompting them once again to take up arms against the whites. Slaves burned down plantations, murdered their white masters, and even attacked the towns. Fighting continued as the new Legislative Assembly (it replaced the National Assembly in October 1791) considered free black rights again at the end of March 1792. On 28 March, the assembly voted to reinstate the political rights of free blacks and mulattos. Nothing was done about slavery.

In the fall of 1792, as the Revolution in mainland France began to radicalize, the French government sent two agents to Saint Domingue to take charge of the suppression of the slave revolt. In order to gain their freedom, rebel slaves now made pacts with the British and Spanish in the area. The British and Spanish promised freedom to those slaves who would join their armies, even though they had no intention of abolishing slavery in their own colonies. They simply wanted to benefit from France's problems. Faced with the threat of both British and Spanish invasions aimed at taking over the colony with the aid of the rebel slaves, the French government agents abolished slavery in the colony (August–October 1793). Although the National Convention initially denounced this action as part of a conspiracy to aid Great Britain, the Convention eventually voted to abolish slavery in all the French colonies on 4 February 1794. Many mulattos opposed this move because they owned slaves themselves. After more than two years of rebellion, invasion, attack, and counterattack, the economy of Saint Domingue had nearly collapsed. Thousands of whites fled to the United States or back to France.

For all the deputies' good intentions, the situation remained confused in almost all the colonies: some local authorities simply disregarded the decree, others converted slavery into forced labor, others were too busy fighting the British and Spanish to decide one way or the other. Out of the fighting emerged one of the most remarkable figures of the era, Toussaint L'Ouverture, a slave who learned to read and write and in the uprising rose to become the leading general of the slave rebels. Toussaint faced incredible obstacles in creating a coherent resistance. By 1800 the plantations were producing only one-fifth of what they had in 1789. In the zones controlled by Toussaint, army officers or officials took over the big estates and kept the former slaves working under military-style discipline. In 1802, once he had consolidated his hold on power in mainland France, Napoleon Bonaparte reestablished slavery and the slave trade in those colonies still under French control and denied political rights to free blacks. He sent a major expeditionary force to Saint Domingue to enforce his will. It captured Toussaint and sent him back to France, where he died in prison. Nevertheless, the former slaves continued their revolt and in 1804 they established the independent republic of Haiti. The French army limped home after losing thousands to disease and sporadic fighting. A slave rebellion had succeeded.

Americans in the new United States followed the events in Saint Domingue with anxious interest. Since the southern states relied on thousands of slaves to work their plantations, a slave revolt in the world's richest plantation colony was bound to excite their concern. In addition, when white settlers began fleeing Saint Domingue, many of them came to the United States. Newspapers in the United States published letters offering eyewitness accounts (and rumors) about the uprising. The accounts in the Pennsylvania Gazette are excerpted here.

Primary Sources

Credits

From LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION, https://revolution.chnm.org/exhibits/show/liberty--equality--fraternity/slavery-and-the-haitian-revolu