Short Teaching Module: Teaching the Intersection of Gender and Race through Colonial Medical Texts

Overview

This module focuses on medical texts written by British doctors working in India and their gendered and racial categorization of ailments and diseases. A detailed analysis of medical texts from the nineteenth century shows the ways in which medical practitioners in Colonial India dedicated much of their time to treating female issues such as menstrual cramps, hysteria, and labor pains. The other gendered medical concerns found in medical texts are treatments for venereal diseases, which practitioners described as female diseases. The gendering of venereal disease paralleled the expansion of the British Empire, because British laws often promoted and guaranteed soldiers’ access to colonial subjects’ bodies. The need to cure the female body often went hand in hand with the expansion of Empire, the sexual availability of colonial women, and maintaining racial boundaries between colonizers (who the British regarded as having healthy bodies) and colonized (who the British saw as diseased). Feminist scholars connect medical practices in the 19th century with the institutional subordination of women in Britain and Colonial India, and medical texts written by doctors in the late 1880s reveal the connection between epistemology and racial and gender hierarchies in Colonial India. This module uses medical texts to explore the connection between colonialism, medicine, gender, and race.

Essay

By the 1760s, British botanists and soldier/surgeons collected plant specimens in South Asia for the express purpose of discovering new drugs and materia medica. Archival records detailing the uses of medicinal plants included gendered descriptions of venereal disease and defined female bodies (both in Britain and across the Empire) as objects in need of curing. This teaching module provides suggestions on how to use medical publications by British and Indian medical practitioners, which not only provides insights into the categorization of medical issues based on gender and race but also the intersection of these categories in treating medical conditions.

Medical practitioners were influenced by scientific racism and determined that “natives” reacted to and needed different treatment than Europeans in colonial India.

Miscegenation laws and cultural taboos strengthened in the latter half of the nineteenth century to maintain access for British men to local women but to prohibit British women from having relationships with local men. Control of women’s bodies (both white and brown) was essential to keeping control of “civilization” which is why many medical professionals and scientists categorized women and people of color as inferior, in need of protection, and in need of civilizing. Controlling venereal diseases ranked high in importance to colonial officials, but medical texts categorized venereal diseases as female diseases, spread by women and cured by men. Defining ailments and cures in gendered and racial terms legitimized colonial hierarchies that were essential to imperial rule.

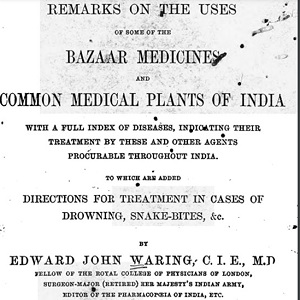

The medical text explored in this module, Edward J. Waring’s, Remarks on the Uses of Some Bazaar Medicines, provides a hegemonic example of medical practices formulated around gendered and racial ideology of the late nineteenth century. Waring obtained a great deal of the indigenous plant knowledge regarding medicinal plants and their uses from local people he vaguely referred to as “Natives.” He stated in the preface to the 1883 publication, “I am perfectly prepared to admit that much of the knowledge I possess of the properties and uses of Indian drugs has been derived from Native sources.” (Waring, pg. xii) He forgives this appropriation directly after this statement by claiming to have discovered uses of medicinal plants unknown to local people. Therefore, in Waring’s estimation, the information he presented, a combination of indigenous knowledge and his own experimentation with medicinal plants in South Asia, was intended to educate all people--whether missionaries, civil servants, soldiers, or South Asians--on the procurement, creation, and application of medicines. Curing the female body was part of a larger endeavour among European men to treat the female body as an object of scientific study, one from which women themselves were excluded. By treating female bodies as objects of study, surgeons silenced the contributions of local indigenous women to materia medica knowledge.

Naturalists and medical professionals traveled with expanding British armies thought it was imperative to collect and codify local indigenous plant knowledge particularly of medicinal plants to create medicine in the field. Waring is one example of a medical professional who compiled local indigenous plant knowledge into a book and included “native” names to make it easier for surgeons to obtain the drugs in local markets. By the end of the nineteenth century, the small act of giving credit to local people for the medicinal knowledge provided by them in their language was largely absent in medical publications such as Waring’s book. This middle period highlights the concerted effort by naturalists and surgeons (often one and the same) to obtain local indigenous plant knowledge and utilize it to treat soldiers and civilians alike while also erasing the context and contributions of local people in creating knowledge.

This medical text provides an interesting opportunity to discuss the intersection of gender and race in the later colonial period. For classes focused on colonialism, gender and empire, natural history collecting, or the history of science and medicine, these medical texts offer a glimpse into the minds of doctors as well as their motivations for treating patients and the historical context within which they created knowledge. Medical texts provide opportunities to focus on the intersection of gender and race in the development of both medical knowledge and colonial hierarchies. Medicines categorized as useful for “natives” were not the same as for white patients, despite the ailment being the same. Power dynamics of epistemology clearly played out in the creation of the book since Waring admits to compiling much of his information based on local knowledge and he depended on local scholars (and doctors) to translate the names into several languages. His book, in effect, is a perfect example of the types of cross-cultural exchange that occurred in the late 19th century colonial world: a European (British in this case) professional man gathers local information and combines it with his formal education obtained in Europe and writes a book to share his discovery with other professionals (primarily other European men). Waring is unique in that he does give credit to some of the local assistants (professionals in their own right) but leaves out the vast majority of people that made the book possible.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Philippa Levine, Prostitution, Race, & Politics: Policing Venereal Disease in the British Empire (London: Routledge, 2003).

Matthew James Crawford, The Andean Wonder Drug: Cinchona Bark and Imperial Science in the Spanish Atlantic, 1630-1800 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016).

Londa L. Schiebinger, Plants and Empire Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004).

Ikechi Mgbeoji, Global Biopiracy: Patents, Plants, and Indigenous Knowledge (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2006).

Credits

Carey McCormack, PhD, is an instructor of world history at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. Her teaching and research focuses on the Indian Ocean World, gender/sexuality in the colonial period, environmental justice, and indigenous plant knowledge. Her previous publications explore indigenous plant knowledge and the development of botany in South and Southeast Asia during the nineteenth century as well as the interconnection between knowledge creation, gender, and colonial subjectivity.