Short Teaching Module: East Asian Developmental States in Global History

Overview

The essay examines the concept of the “developmental state” in East Asia, tracing its evolution and application across both capitalist and socialist regimes of the twentieth century. It highlights how Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea achieved rapid economic growth post-World War II through state-guided industrialization, influenced by historical models of state intervention in Europe during World War I, the Soviet Union, and imperial Japan during World War II. The essay also explores the developmental state’s relevance to China's economic transformation before, during, and after the Mao period (1949–76), suggesting significant connections between different periods of twentieth-century China. By integrating the histories of both capitalist and socialist industrialization efforts, the essay underscores the broader, transnational genealogy of the developmental state in East Asia and beyond.

Essay

East Asia’s economic development after World War II provides rare cases of non-Western countries catching up with the developed economies in North America, Western Europe, and Oceania. During the 1950s and 60s, the Japanese GDP grew at about 10% per year, and from around the 1970s, Taiwan and South Korea experienced even faster growth. Scholars have presented a variety of explanations for the “East Asian miracle.” A particularly influential concept is the “developmental state”—a term coined by political scientist Chalmers Johnson in his book MITI and the Japanese Miracle (1982). According to Johnson, in post-WWII Japan, the state bureaucracy guided private enterprises toward industrialization through methods such as protectionist tariffs and low-interest loans. The concept was later applied to other Asian countries, such as Taiwan, South Korea, and most recently, China.

Although most scholars used the developmental state concept to explain differences among capitalist regimes, the exclusion of socialism from the discussion is problematic, given that the largest East Asian economy, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), defines itself as a “socialist” state. Historians have studied the “developmental state” in pre-Communist China and its legacy in the aftermath of the Communist Revolution. Social scientists applied the developmental state concept to China’s market-oriented reform from the late 1970s, while stressing the persisting legacies of the planned economy. The case of China suggests that some important connections might have existed between the developmental states and the socialist regimes.

This essay reconsiders the transnational genealogy of the developmental state both under capitalism and socialism. The practice of the developmental state was a product of decades of experiments by differing late-industrializing regimes in East Asia and beyond. Whether under socialism or capitalism, these regimes made attempts to catch up with the advanced industrial economies, collectively called the “West,” through various forms of state guidance.

World War I of 1914-18 redefined the relationship between the state and industry globally. To enhance their military capacity, the major European governments directly controlled many realms of the economy. This shared experience of total war inspired the Bolsheviks, who seized power in Russia in November 1917. In 1918, Vladimir Lenin wrote that “our task is to study the state capitalism of the Germans, to spare no effort in copying it.” The Bolsheviks began to place major industrial enterprises under state ownership.

The Soviet Union, established in 1922, continued to be inspired by the models of advanced industrial economies. Thousands of copies of Henry Ford’s autobiography were circulating in Russian translation. The Soviet Union imported machines and invited experts from American or German companies, especially during the First Five-Year Plan (1928–32).

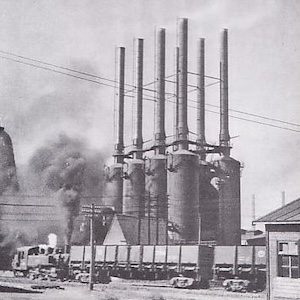

The Soviet Union’s extremely high pace of industrialization impressed many non-Western policymakers and intellectuals, including Japanese bureaucrats in Manchuria (Northeast China), which Japan occupied between 1931 and 1945. Partly emulating the Soviet Union, the Japanese-sponsored government of Manchukuo implemented five-year plans for state-directed heavy industrialization. But rather than place all the industries under state ownership, the Manchukuo government also allowed private businesses, many of which were owned by the Japanese, to operate in Manchuria.

Many Japanese bureaucrats of Manchukuo were later transferred to Japan, where they brought home their recent experiment of regulated capitalism during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–45) and the Pacific War (1941–45). The core of Japan’s wartime economic mobilization was the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MCI), which introduced various forms of bureaucratic control on private enterprises.

After Japan’s surrender in the summer of 1945, the U.S. occupation (1945-51) changed Japan’s state structure considerably through demilitarization and democratization. Nevertheless, the U.S. occupation reform towards Japan’s prewar bureaucratic and economic elites was not as far-reaching as reforms in other fields. The pre-1945 civilian bureaucracy, including the MCI, remained almost intact.

During the 1950s and 1960s, Japanese government officials developed select private industries through their control over foreign exchange and imports of technology, low-cost loans, tax breaks, and orders to create cartels and bank-based industrial conglomerates. Especially important was the successor of the MCI, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry, the subject of Johnson’s MITI and the Japanese Miracle (1982). The post-WWII Japanese developmental state, at least partly, built upon the legacies from the pre-1945 period.

The government’s role was even stronger in Japan’s former colonies, South Korea and Taiwan, which arguably built upon colonial-period institutions even after 1945. In post-WWII Taiwan, the government controlled the banking sector and used it to finance state-owned enterprises rather than private ones. In South Korea, Park Chung Hee, a Japan-educated military officer, established an authoritarian regime in 1961 and nationalized the banking sector to mobilize savings and direct investment. These patterns differed from Japan, where despite the bureaucratic influence of the state, major financial institutions and most manufacturing enterprises were privately owned. The economic growth in Taiwan and South Korea was also more export-oriented than that in Japan.

The East Asian “developmental state” was widely discussed among scholars in the 1980s and 1990s, but the concept came to receive less attention by the 2000s as the Japanese economy stagnated and a model based on its experience lost appeal to many observers. Recently, however, the developmental state concept saw a revival, not least because of China’s economic rise and scholars’ attempts to explain it with a “developmental state” model. This essay ends with an overview of the making and remaking of the Chinese developmental state.

Historians have used the developmental state concept to refer to China’s Nationalist government (1927–49), especially during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-45). Inspired by state-directed industrialization in imperial Japan, Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union, the National Resources Commission (NRC) of the Nationalist government founded and developed a variety of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in heavy and military industries to resist Japan’s military threat and aggression. Following Japan’s surrender in 1945, the NRC confiscated Japanese-controlled factories and reorganized them into SOEs. Many NRC members thus moved to formerly occupied parts of China, especially Manchuria.

When the Communists led by Mao Zedong founded the People’s Republic of China in 1949, a substantial proportion of Chinese industry, especially in Manchuria, was already under state ownership because of the Nationalist SOE system. Many NRC staff stayed to work in the early PRC. While building on the pre-Communist legacy, the early PRC tried to build socialism by emulating the Soviet system of planned economy and importing technology from the Soviet Union. From the late 1950s, however, the deterioration of Sino-Soviet relations led the PRC to pursue China’s own version of socialism.

After Mao Zedong’s death in 1976, the PRC gradually introduced the system of a market economy. Despite dramatic changes, however, the post-Mao system also built upon the legacies of the Maoist period. Importantly, the PRC party-state continues to control strategically important sectors, such as energy, telecommunication, and banking, through gigantic SOEs. The continuous evolution of the Chinese SOE system under the Nationalist, Maoist, and post-Maoist periods show that the East Asian developmental states were products of the longer global history of catch-up industrialization under socialism and capitalism.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Allen, Robert C. 2011. Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

Bian, Morris L. 2005. The Making of the State Enterprise System in Modern China: The Dynamics of Institutional Change. Harvard University Press.

Haggard, Stephen. 2018. Developmental States. Cambridge University Press.

Harrison, Mark. 2017. “Foundations of the Soviet Command Economy 1917–1941.” In The Cambridge History of Communism, edited by Silvio Pons and Stephen A. Smith, 1:348–76. Cambridge University Press.

Hirata, Koji. 2021. “Made in Manchuria: The Transnational Origins of Socialist Industrialization in Maoist China.” The American Historical Review 126 (3): 1072–1101.

Hirata, Koji. 2023. “Industry,” in Andrew Denning and Heidi J.S. Tworek (eds.), The Interwar World. Routledge: 636–655.

Hirata, Koji. 2024. Making Mao’s Steelworks: Industrial Manchuria and the Transnational Origins of Chinese Socialism. Cambridge University Press.

Johnson, Chalmers. 1982. MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975. Stanford University Press.

Leung, Ernest Ming-tak. “Developmentalisms.” Phenomenal World, September 2021. https://phenomenalworld.org/analysis/developmentalisms.

Lenin, V. I. (1918) 2002. “‘Left-Wing’ Childishness.” Marxist Internet Archive. https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1918/may/09.htm.

Link, Stefan J. 2020. Forging Global Fordism: Nazi Germany, Soviet Russia, and the Contest over the Industrial Order. Princeton University Press.

Sawai, Minoru 沢井實, and Tanimoto Masayuki 谷本雅之. 2016. Nihon keizai shi: Kinsei kara gendai made 日本經濟史:近世から現代まで. Yūhikaku.

O’Rourke, Kevin H., and Jeffrey G. Williamson, eds. 2017. The Spread of Modern Industry to the Periphery since 1871. Oxford University Press.

Zheng, Yongnian, and Yanjie Huang. Market in State: The Political Economy of Domination in China. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Credits

Koji Hirata is Senior Lecturer/Senior Research Fellow in History at Monash University. He earned his Ph.D. in history at Stanford University. He was a Research Fellow (JRF) at Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge, before coming to Monash. His research focuses on modern China, Japan, and Russia/Soviet Union, with broader implications for the global history of capitalism and socialism. His new book, Making Mao's Steelworks: Industrial Manchuria and the Transnational Origins of Chinese Socialism, was published by Cambridge University Press in December 2024 (https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/making-maos-steelworks/A4E9283F0FE304448D3D8B98CAF1E42F). Between 2024 and 2026, he serves as an ARC DECRA research fellow, working on his new book project on Maoist China’s foreign trade.