Browse Primary Sources

Locate primary sources, including images, objects, media, and texts. Annotations by scholars contextualize sources.

Gallic Declaration of War, or, Bumbardment of all Europe

This scatological English cartoon mocks France’s claim that it was going to war for "liberty," suggesting instead that France’s body politic is ill and that England needs to fight back to defend itself from such sickness.

The Queen of Louis XVI King of France at the Guillotine, 16 October 1793

An idealized portrait of Marie Antoinette at the moment of death. Unlike the pale, aged woman the contemporaries observed, this later print memorialized a beautiful, absolutely pure, woman. While in life she had been assailed as a lesbian, a pedophile, and an adulteress with men, here she is being depicted as nearly a saint.

Execution of Marie Antoinette (16 October 1793) at the Place de la Révolution

This postcard in English and French does show the broader scene at the execution of the Queen. Before the guillotine stands Marie Antoinette with Sanson, the same executioner who had dispatched her husband ten months before. Surrounded by soldiers, and tens of thousands of onlookers, she awaits the moment of death. Also on the platform is Marie Antoinette’s confessor.

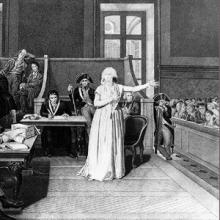

Image of the Queen’s Defense

The trial of the Queen is here depicted in a tinted engraving by Jean Duplessi–Bertaux as part of his series of Historical Scenes of the French Revolution. Although it refers to her as "Marie Antoinette, the Austrian," the etching portrays her somewhat sympathetically, showing her in a graceful pose with a concerned look on her face amid a hostile prosecutor, judge, and soldiers.

Trial of Marie Antoinette of Austria

Some months after the execution of her husband, Marie Antoinette found herself in the dock of the public prosecutor, Antoine Quentin Fouquier–Tinville. The intervention of the radical journalist Jacques–René Hébert had pushed her case to the top, and she was accused most notably of immorality and treason. She defended herself bravely and calmly, as the above image suggests.

The Queen Exhausted

An image produced well after the Revolution shows a Queen, assaulted by the gaze of the people, controlled by the soldier, and tentative in her stance and appearance.

Hell Broke Loose, or, The Murder of Louis

In this English image, as the King’s head is about to fall into the executioner’s basket, bats out of Hell emerge, symbolizing the Revolution. At the same time, God’s favor seems to fall on Louis through a shaft of light coming from heaven. From the first, some English, especially Edmund Burke, were skeptical, indeed critical of the Revolution, and the numbers grew over time.

Louis XVI, King of France, born 23 August 1754, beheaded 21 January 1793

Louis quickly became a matyr to the royalist cause, as this and other memorials indicate.

Louis Arrives in Hell

In classical mythology, the journey to Hell involved crossing the river Styx. Revolutionary cartoonists often invoked this image when describing the fate of their enemies. This is no exception. See the boat on the left with the dog, Cerberus, who was the guardian of the gates of the underworld. Arriving here is the headless Louis, greeted by other prior monarchs.

Rare Animals; or, the Transfer of the Royal Family from the Tuileries to the Temple. Champfleury, 1792

Here the events of 10 August were expressed by reducing the royal family to animals. Driven from their palace to prison, the family became no more than a group of barnyard animals. Contrast these common four–footed animals with the erect revolutionary whipping them along.

King and Queen as Two–headed Monster

The Queen, never popular to begin with in France, also bore the brunt of popular anger in 1792, as seen in images of the King and Queen as animals. This reversal from old regime portrayals of the monarchy is made more remarkable by the fact that beyond 1789 cartoons tried, if somewhat unsuccessfully, to integrate royalty and revolution.

Louis Rides a Pig

Equestrian skills were expected of a monarch. But portraying the King mounted on a pig was most unflattering. Linking royalty to animals was a theme that emerged after the flight to Varennes.

Louis as No More Than a Man

Part of the revolutionary undermining of the monarchy becomes evident in this profile of Louis XVI, shown here without his wig or finery.

Louis as a Drunkard

This image of Louis, already altered by commoner attire and a Phrygian cap, added a raised bottle. This transformation could scarcely have been anticipated even a year or two into the Revolution.

Louis as a Drinker

The arrest of the King prompted an outpouring of sentiment against Louis. Like his grandfather, Louis XV, whose early reputation as "Louis the Well–Loved" faded by the end of his long reign, Louis XVI now became the focus for all sorts of discontents. This image depicting Louis as incapable of governing himself, let alone France, reveals the depth of the scorn expressed.

Louis XVI, King of the French, born 23 August 1754.

Early in the Revolution, LaFayette was among the most visible and popular leaders, in part because of his participation in the American revolution and his relationship to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and others. Further, though noble, he had been sympathetic to the Third Estate.

Long Live Liberty

Cartoonists extrapolated more and more on a new Louis as the Revolution went along. Here, a rather rumpled King, dressed more like a shopkeeper than a monarch, opens a cage to let liberty out. Many scholars argue that the King was already desacralized as much as a couple of decades before the Revolution.

Louis XVI, King of the French

This fascinating print, likely produced before the King’s flight from Paris, takes the Louis XVI of the old regime and makes him a revolutionary with the addition of the Phrygian cap. While the engraver’s intention remains absolutely unknown, contemporaries might have seen this as mocking Louis’s new position in the Revolution.

Louis XVI

Here was the "body politic" of the old regime. Theoretically, France existed only as an entity in the body of the King. The citizens were his subjects; the geographical parts linked together only through the monarch. Robed and wigged, he was an emblem of a centuries–old regime.

Execution of Louis XVI, January 21, 1793, 10:22 in the morning

This image shows much the same scene on the platform as the preceding one, but the surroundings are much more in evidence. Visible here are the troops. Eight to nine thousand were mobilized to avoid any efforts at rescue. This is clearly the last moment as Louis XVI has his coat off and his hands secured behind his back. The confessor steadies the King.