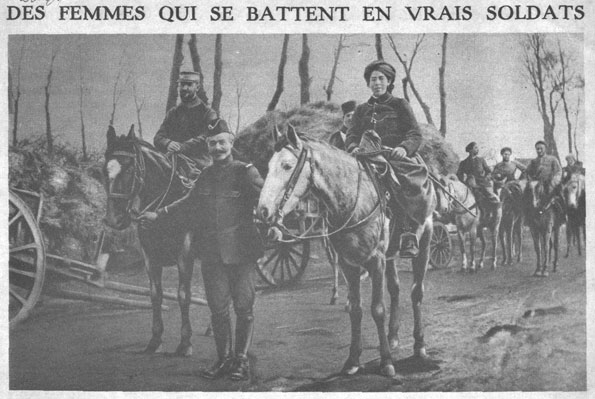

Photograph of Fatima the Moroccan

Annotation

By 1900, only the Kingdom of Morocco remained more or less independent of European rule, although European competition for Morocco was intense between Spain, France, and Germany. Between 1899 and 1912, French armies progressively occupied the country using Algeria as a base. In 1912, the French and Spanish protectorates were declared, with the lion’s share of Moroccan territory going to France. Nevertheless, it took France several decades to quell the numerous rural revolts sparked by military occupation. These rebellions had scarcely been suppressed when the Moroccan nationalist movement emerged in the post-World War I era. One of the ironies of colonialism is that native peoples worldwide were forced into the imperial armies of the French, British, Italian, and other empires. Moroccan soldiers served under the French flag—as did Algerian and Tunisian soldiers—in large numbers. Some were forced into the army against their will; others were enrolled as “volunteers”—“perfect mercenaries” for combat in Europe or other French possessions worldwide. During World War I, France sent tens of thousands of North African soldiers to fight in the trenches in Europe, where they often were deployed as “cannon fodder.” Some 173,000 Algerians served in the French army during the “Great War.” In addition, the North African units were segregated from French soldiers and often housed and fed in an inferior manner compared to European combatants.

At the same time, the European empires employed propaganda to enlist women in the war effort—for example, by laboring in jobs traditionally restricted to men, such as manufacturing weaponry. Women as warriors, as soldiers, women bearing arms, however, has always been problematic. Thus, this photo from the French newspaper, Le Miroir, dated June 13, 1915, is entitled “Women who fight as real soldiers,” raises many issues. The text reads: “Fatima [Fathima in French], the Moroccan woman, whose portrait we reproduce here, followed into battle from the beginning of the war our [North African] units and fought courageously like a man.”

We have no other information on Fatima, the Moroccan, or how she got to the European front during the war. Did she disguise herself as a man? Historically speaking, this was a way that women seeking to fight could do so. Or was she already in France before the war and subsequently volunteered when Moroccan units, perhaps including male family members, arrived to fight with France against Germany? And what propaganda uses were made of her image? Was the photo of her, dressed in a soldier’s uniform, meant to encourage Moroccan soldiers fighting in a strange land for a cause that was not theirs? Or was this image aimed more at European audience, intending to demonstrate the loyalty of the colonized in a world war of Europe’s own making? The questions are endless. Although one hint lies in the weekly Le Miroir’s statement that it “would pay any price for photographic documents relating to the war and presenting a particular interest to the public.”

Nevertheless, one thing is certain—this image contrasts with the depiction of “Belle Fatima,” the sensuous woman clothed in oriental finery and posed reclining in a studio photograph in accordance with the dictates of European male fantasies.

This source is a part of the North African Women and the French Empire, 1850-2000 teaching module and the Primer: Imperialism methods module.

Credits

“Fatima the Moroccan.” Le Miroir. 5eme année, number 81. June 13, 1915.