Short Teaching Module: Filipino Comfort Women

Overview

This lesson on Filipino “comfort women” fits into a women’s history course. I chose this topic because it exposes the false dichotomy between being a victim and being a forceful advocate for your cause. These women prefer the word “survivors” as opposed to the word “victims” to describe themselves. While they were clearly victims of rape and military sexual slavery during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, by telling their stories and participating in protest work, they have become feminist activists and advocates. Thus, this topic can also be taught as part of a history course that focuses on the uses of oral history.

Essay

The issue of Japanese-enforced military sexual slavery during the Japanese occupation of Asia only began to be publicly discussed in the 1980s. Before then, it had been a taboo subject. The Japanese have refused to acknowledge that it actually happened in their history textbooks. Moreover, the stigma of shame and rape meant that the women had kept silent for many decades after the war. The only primary sources for this topic are the oral testimonies of the former victims of rape.

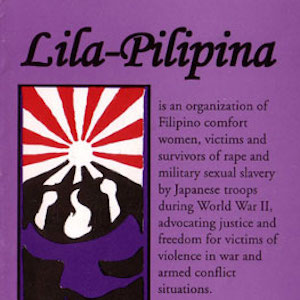

I would like the students to see these testimonies as a form of performing oral history—a spectacle of protest. Many of the Filipino “comfort women” come from the urban poor. Their victimization has resulted in a life of poverty; as social victims, they were forced to leave their villages and move to the city, where, deprived of an education, they were compelled to remain in low-paying jobs such as laundry women and salesgirls. Despite this deprivation, once these women become members of Lila-Pilipina (the organization of “comfort women”), they become graduates of a feminist education. Thus, these stories are not merely memories of the war or stories of rape and victimization. They are a form of protest politics in which women demand compensation from the Japanese government as well as an apology and the rewriting of official national histories in textbooks. They are also feminist protests. The women become feminist advocates—they are linked to feminist transnational organizations with other “comfort women” in Asia, as well as feminist groups in Japan, and they ally with other feminist organizations campaigning for “a world without war.” In telling their stories, I’d argue, these women become transformed from victims into feminist advocates.

Scholars writing on this topic have been either feminist scholars or scholars of World War II. Historians who grapple with the theory and practice of oral history have largely neglected this issue as part of performing oral history as spectacle of protest.

I recommend teaching this topic over three weeks or three discussion sessions. I suggest that the students read the secondary sources first, then the biography of Maria Rosa Henson. For the last exercise, they analyze the Lila-Pilipina brochure and the group of photographs depicting two scenes: (1) Filipino “comfort women” giving their testimonies to Japanese Tourists in Manila, and (2) Filipino “comfort women” demonstrating in front of the Japanese Embassy in Manila.

In the first session, students should be asked to read the secondary literature on the field. I suggest they focus on the feminist scholarship on the topic.1 Usually I require students to write answers to questions in a journal that I collect at the end of each class. This technique is to ensure students do the reading before class and participate in an informed manner (they refer to their journal in class). They get a mark for each journal exercise. During the first week, students answer questions about the authors’ arguments.2 In the second week, students focus on the primary sources, by reading and journaling3 about Maria Rosa Henson’s autobiography, Comfort Woman Slave of Destiny.4

The last discussion session focuses on Lila-Pilipina—the organization of Filipino “comfort women” who are members of the GABRIELA (General Assembly Binding Women for Reforms, Integrity, Equality, Leadership and Action), an umbrella organization of more than 200 grassroots women’s organizations. GABRIELA is a militant women’s organization that is unabashedly feminist in orientation, with a national democratic bent. The sources include a brochure of the Lila-Pilipina group, an issue of Piglas-Diwa (newsletter publication of their Center for Women’s Resources) focusing on the “comfort women,” and a series of photographs taken of “comfort women” telling their stories to Japanese tour groups and demonstrating in front of the Japanese Embassy in Manila in August 2003. I ask students to consider the use of oral history as performance protest in this material. At the same time, I ask them to think about the self-representation of the “comfort women” in the brochures and the photographs.

The Lila-Pilipina brochure and the Piglas-Diwa newsletter/booklet serve as primary sources that reveal how Lila-Pilipina wants to represent itself. The discussion can be divided into two parts. In the first half, I ask students to explore how Lila-Pilipina and the “comfort women” represent themselves in the brochure and booklet. Do they present themselves as victims or feminist advocates? What are their demands and what are their strategies for achieving them? At this point, I remind students that the struggle is not just against the Japanese government but also against the Filipino government, which has also ignored them and has resisted including their stories in the country’s national histories. I then direct students to think about the first week’s reading by Hyun Sook Kim where the Korean government is reluctant to support the “comfort women” and their cause because it reflects the nation’s crisis of masculinity.

Photographs 1-3 show the lolas (Filipino word for grandmothers—the term used for Filipino “comfort women”) telling their stories to a group of Japanese tourists. Four lolas were asked to meet with Japanese tourists, though only two actually told their stories. The photos show Lola Asiang telling her story in Tagalog (Filipino). First, her words are translated into English and then into Japanese. So this is a slow process. As she tells her story of rape and imprisonment, she breaks down in tears. But at the end of her story she finishes with a militant protest: “It has been 11 years and there is still no justice. I thank all of those who have helped us. We are not going to stop, even our president is not listening to us. Thank you to Lila-Pilipina. I only want justice. Tell the government to respect the rights of women who are victims of Japanese soldiers. It is hard to tell my story, I just bear it.”5 After two lolas tell their stories, Richie Extremadura, the Director of Lila-Pilipina, introduces the audience to Lila-Pilipina, summarizing its history, its court cases, and its demands from the Japanese and Philippine governments. The organization’s brochure summarizes this information as well. Then there is a short question-and-answer period.

It is important for students to know that this activity can be interpreted as a spectacle or performance, since the lolas tell their stories several times according to a set script. The lolas know that telling their stories moves both them and the audience to tears, and that the story will finish with a cry for justice. Pamela Thoma, in a reading from week 1, was troubled by the “comfort women’s” testimonial becoming something close to a spectacle, since the Korean woman’s story was retold by an interpreter. Thoma saw this use of an interpreter as a “compromise.” Simonie Smith’s chapter is also structured around a “comfort woman’s” testimony at the University of Michigan. Students should be asked if they view the performance of oral history as spectacle as something that troubles them or as a necessary strategic act of protest. Simonie Smith also raises the point that telling these stories also relives the trauma for these survivors who have to relive the experience again and again.

Photographs 4-15 show Lila-Pilipina protesting on Memorial Day, August 14, 2003, in front of the Japanese Embassy in Manila. They arrived with banners and protested for about an hour, giving speeches and chanting slogans. Part of their protest included a dance/drama. The dance/drama was a metaphor for their life memories. The first part of the show was a rural traditional folk dance with women in national dress, including some dressed as men. This was supposed to represent their happy life in the countryside before the war. The next and final part of the performance showed a group of soldiers throwing the women violently to the ground. Then the dance-drama abruptly ended. Director of Lila-Pilipina, Richie Extremedura, revealed in my interview with her that if the lolas had their way, they would have reenacted the rape scenes, but Richie had censored this from the script. Afterwards, the women tied black ribbons with the words “Justice Now!” all over the grounds of the Japanese Embassy. When this was accomplished, the women got into their bus and drove away to a prearranged picnic in the park.

I ask students to analyze these photos and texts sources for evidence of self-representation. How does Lila-Pilipina represent itself? The demonstration is a staged event, and although I took the photographs and they were candid shots taken in available light, the scene was a script written by the women themselves. Students should systematically analyze the photographs: they can analyze the women’s dress (t-shirts with Lila-Pilipina logo, rural national dress), deportment (clenched fists, militant stance), and accessories (the signs they carried). For example, none of the lolas there spoke fluent English, and yet all the signs were in English. The demonstration was orchestrated for the press and for the Japanese Embassy who were the target audiences. Certainly, despite their advanced age, these women looked much younger (they are in their seventies and eighties). They appeared militant and sad at the same time. But they did not look weak. They stood with arms raised and clenched fists. And they all carried signs in English making pointed statements (this could also be analyzed). One could also analyze the use of national dress (which blends with the definition of woman as bearer and wearer of “tradition” and the association of native dress with the pre-rape days). What messages (semiotics) do the photographs convey? There was certainly an aura of spectacle complete with dance/drama and the dramatic ribbon-tying ending.

The demonstration was particularly poignant because Lila-Pilipina is aware of the obstacles facing them. The lolas themselves believe that the Japanese government strategy is to wait for them to die, hoping that the issue will disappear with their demise. Since the organization was founded, 38 out of the 173 lolas have died. It is the knowledge that they are in their twilight years that imbues the performances of oral history with more urgency. And therein lies the “imaginative power” (to borrow Laura Hein’s phrase) of the “comfort women” issue. While their oral histories as live performance are primarily protests against patriarchal governments, the performance have caused profound changes for the women themselves. Since the governments refuse to listen to their impassioned please for recognition, hoping that the protest will die out quite literally, the impact of the testimonials has not been in the big picture—not in the arena of national and transnational history and memory—but in the transformation of the victim into militant feminist.

Through these exercises, students learn that women’s histories often conflict with national histories and national memories. The women featured here are former victims who use oral history as a performance protest in order to achieve feminist goals as well as to contest national memories of war. Thus, women “survivors” can be both victims and advocates. They also represent themselves in ways that would empower themselves and make their demands known.

1They should start with: Sidonie Smith, “Belated Narrating: “Grandmothers” Telling Stories of Forced Sexual Servitude during World War II”, in Wendy S. Hesford and Wendy Kozol, eds., Just Advocacy? Women’s Human Rights, Transnational Feminisms, and the Politics of Representations, (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2005), pp. 120-145. Then I recommend the following: Laura Hein “Savage Irony: The Imaginative Power of the “Military Comfort Women” in the 1990s”, Gender and History, Vol, 11, No. 2, July 1999, pp. 336-372, Hyun Sook Kim, “History and Memory: The “Comfort Women” Controversy”, Positions, Vol 5, No. 1, 1997, pp. 73-106, and finally, Pamela Thoma, “Cultural Autobiography, Testimonial, and Asian American Transnational Feminist Coalition” in the “Comfort Women of World War II” Conference, Frontiers, Vol 21, No. 1/2, 2000.

2[HANDOUT] Students should be asked to summarize the arguments made by each scholar. Other suggested questions for discussion are: How does the issue become used as a feminist issue? Do you agree with Pamela Thoma that the performance of oral history at conferences is a spectacle with a negative connotation? Do you think “comfort women” should be performing their oral histories in this way? (After all, it is a well-rehearsed story—something performed repeatedly following a set script to an audience.) In what way is the “comfort women” issue a topic about contesting national memories? Why does the story of the “comfort women” become subsumed in the contest for masculinity and national pride? What does that imply about women’s lives and histories of nation? (See Hyun Sook Kim article).

3[HANDOUT] They could answer the following questions in their journal for that week: What does Maria Rosa Henson’s story let us know about the experiences of “comfort women” in World War II? How does she appear in the story—as a victim, as a survivor, as an advocate or fighter? How has her experience as a military sex slave affected the rest of her life? Do you think of her as a victim or as an advocate? How does her life story reflect the history of Japan and the Philippines? (Is she a victim because the Philippines is a country lower in economic status than Japan?) Is telling her story an attempt to reclaim agency or reclaim dignity for herself or for her country? Compare your own assessment of the autobiography with Simonie Smith’s analysis in the above chapter (in the reading for week 1).

4Maria Rosa Henson, Comfort Woman Slave of Destiny, (Boulder, Rowman & Littlefield, 1999).

5The author’s translation from Tagalog to English.

Primary Sources

Credits

Mina Roces is a Senior Lecturer at the University of New South Wales, School of History, in Sydney, Australia. She is the author of Women, Power and Kinship Politics: Female Power in Post-War Philippines. This teaching module was originally developed for the Women in World History project.