W.E.B. DuBois Details the 1919 Pan-African Congress in Newspaper Article

Annotation

This article comes from Cayton’s Weekly, a historically Black newspaper published in Seattle, Washington. The article, written by W.E.B. Du Bois, offers readers insight into the 1919 Pan-African Congress held in Paris, France. This Congress was comprised of fifty-seven delegates from fifteen nations and European colonial outposts including the United States, the French West Indies, Haiti, France, Liberia, the Spanish Colonies, Portuguese Colonies, Santo Domingo, England, British Africa, French Africa, Algeria, Egypt, Belgian Congo, and Abyssinia. According to Du Bois, delegates expressed their desire to promote racial unity. Some delegates also utilized a human rights discourse, to challenge the legitimacy of racial inequality while the delegate from Liberia presented his country as an example for the rest of the world of a Black republic. France’s Chairman of Foreign Affairs pointed to the fact that France had six chamber members that were persons of color as proof that France was committed to liberty and equality regardless of race. This is contrasted with other white hegemonic states such as Britain and the United States who, despite racial diversity within their populations, lack diversity in government. Several delegates also make reference to the need to people of color to assert and claim rights.

This source is part of the source collection on the Pan-African movement's activism against the global color line.

Transcription

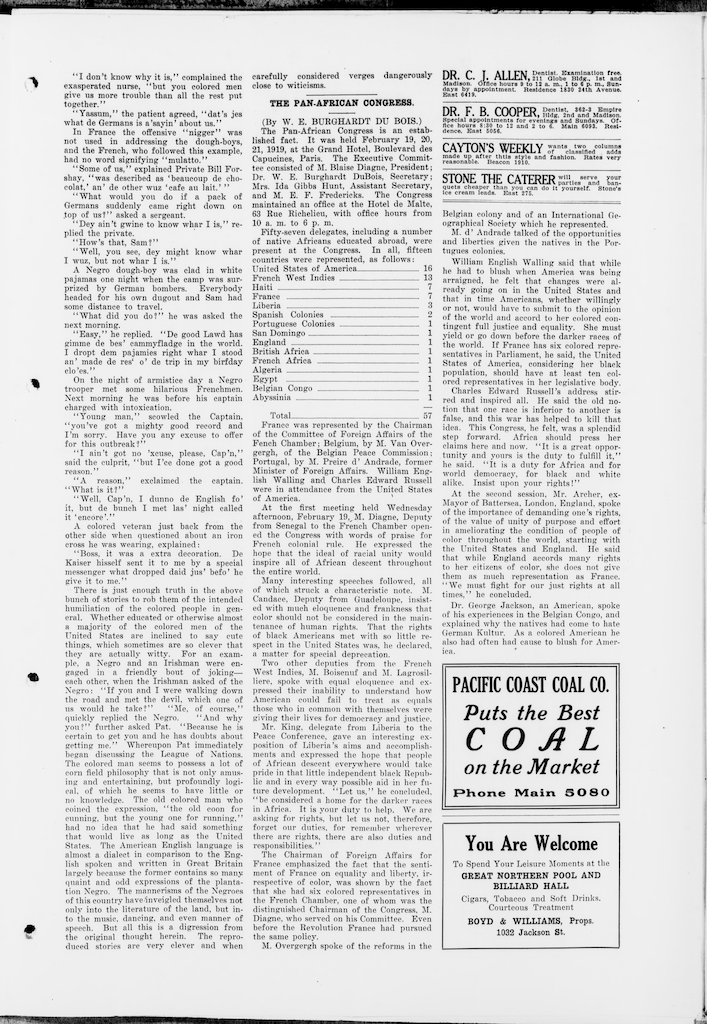

THE PAN-AFRICAN CONGRESS.

(By W. E. BURGHARDT DU BOIS.)

The Pan-African Congress is an established fact. It was held February 19, 20,

21, 1919, at the Grand Hotel, Boulevard des Capucines, Paris. The Executive Committee consisted of M. Blaise Diagne, President; Dr. W. E. Burghardt Dußois, Secretary; Mrs. Ida Gibbs Hunt, Assistant Secretary, and M. E. F. Fredericks. The Congress maintained an office at the Hotel de Malte, 63 Rue Richelieu, with office hours from 10 a. m. to 6 p. m.

Fifty-seven delegates, including a number of native Africans educated abroad, were present at the Congress. In all, fifteen countries were represented, as follows:

United States of America 16

French West Indies 13

Haiti 7

France 7

Liberia 3

Spanish Colonies 2

Portuguese Colonies 1

San Domingo 1

England 1

British Africa 1

French Africa 1

Algeria 1

Egypt 1

Belgian Congo 1

Abyssinia 1

Total 57

France was represented by the Chairman of the Committee of Foreign Affairs of the French Chamber; Belgium, by M. Van Overgergh, of the Belgian Peace Commission; Portugal, by M. Preire d' Andrade, former Minister of Foreign Affairs. William English Walling and Charles Edward Russell were in attendance from the United States of America.

At the first meeting held Wednesday afternoon, February 19, M. Diagne, Deputy from Senegal to the French Chamber opened the Congress with words of praise for French colonial rule. He expressed the hope that the ideal of racial unity would inspire all of African descent throughout the entire world.

Many interesting speeches followed, all of which struck a characteristic note. M. Candace, Deputy from Guadeloupe, insisted with much eloquence and frankness that color should not be considered in the maintenance of human rights. That the rights of black Americans met with so little respect in the United States was, he declared, a matter for special deprecation.

Two other deputies from the French West Indies, M. Boisenuf and M. Lagrosilliere, spoke with equal eloquence and expressed their inability to understand how American could fail to treat as equals those who in common with themselves were giving their lives for democracy and justice. Mr. King, delegate from Liberia to the Peace Conference, gave an interesting ex position of Liberia's aims and accomplishments and expressed the hope that people of African descent everywhere would take pride in that little independent black Republic and in every way possible aid in her future development. "Let us," he concluded, "be considered a home for the darker races in Africa. It is your duty to help. We are asking for rights, but let us not, therefore, forget our duties, for remember wherever there are rights, there are also duties and

responsibilities."

The Chairman of Foreign Affairs for France emphasized the fact that the sentiment of France on equality and liberty, irrespective of color, was shown by the fact that she had six colored representatives in the French Chamber, one of whom was the distinguished Chairman of the Congress. M. Diane, who served on his Committee. Even before the Revolution France had pursued the same policy.

Mr. Overgergh spoke of the reforms in the Belgian colony and of an International Geographical Society which he represented. M. d' Andrade talked of the opportunities and liberties given the natives in the Portuguese colonies. William English Walling said that while he had to blush when America was being

arraigned, he felt that changes were already going on in the United States and that in time Americans, whether willingly or not, would have to submit to the opinion of the world and accord to her colored contingent full justice and equality. She must yield or go down before the darker races of the world. If France has six colored representatives in Parliament, he said, the United States of America, considering her black population, should have at least ten colored representatives in her legislative body.

Charles Edward Russell's address stirred and inspired all. He said the old notion that one race is inferior to another is false, and this war has helped to kill that idea. This Congress, he felt, was a splendid step forward. Africa should press her claims here and now. "It is a great opportunity and yours is the duty to fulfill it," he said. "It is a duty for Africa and for world democracy, for black and white alike. Insist upon your rights!" At the second session, Mr. Archer, ex-Mayor of Battersea, London, England, spoke of the importance of demanding- one's rights, of the value of unity of purpose and effort in ameliorating the condition of people of color throughout the world, starting with the United States and England. He said that while England accords many rights to her citizens of color, she does not give them as much representation as France. "We must fight for our just rights at all times," he concluded. Dr. George Jackson, an American, spoke of his experiences in the Belgian Congo, and explained why the natives had come to hate

German Kultur. As a colored American he also had often had cause to blush for America.

Credits

Library of Congress

Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers

Link: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87093353/1919-04-19/ed-1/seq-3/