Southern Manchuria Railway (1906-1945)

Annotation

The world’s earliest locomotive-operated railroads, short stretches transporting coal and ore locally from mines to factories and furnaces, were developed in Britain between 1800 and 1825. Soon the potential for transporting all kinds of goods as well as passengers became apparent, and by the 1830s railways were also being built in France, Prussia and the United States. Shareholder companies sprang up, hoping to reap rich returns for the heavy (and risky) investments required to build and run new railway networks. Engineers prospered designing new locomotives and new projects. Governments from Turkey to Argentina, perceiving the potential of railways to extend their territorial control and boost revenue-generating economic activity, likewise invested heavily in railway construction. In the United States, white settlement of the Midwest in the 1860s and 1870s followed the extension of the railroad network into the prairies. Russia established its first locomotive factories in the 1850s, and by the late 1870s its railways had crossed the Urals: Siberia became an exporter of wheat and dairy, and the Russian Empire extended to Vladivostok on the Pacific coast. In its newly conquered territories of Central Asia, the Russian government built railways primarily to transport troops and weapons and maintain military control. This was also one important function of the railways built by the British in colonial India.

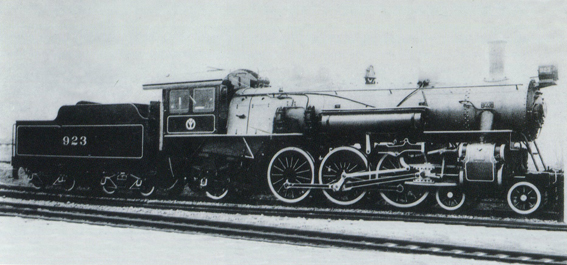

In 1905, seeking colonies of its own, the rapidly industrializing nation of Japan defeated Russia in a war over access to Manchuria and Korea. Japan took over the railways that Russia and China had already constructed in the region, amalgamating and extending them to form the Korean Government Railway (Sentetsu) and the South Manchuria Railway (Mantetsu). In the 1870s Japan had employed British engineers to design and construct its first national railways and to train engineers. By 1900 not only did Japan rely on its own engineers, but it was producing its own engines. The 1921 4-6-2 (Pashishi) locomotive shown here was designed specifically for Korean conditions.

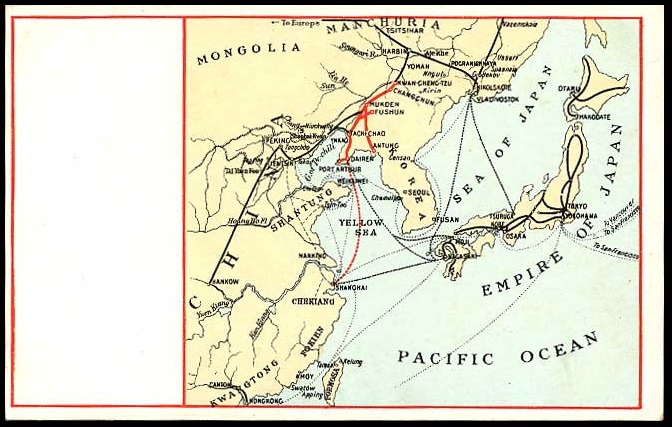

Railways were at the core of Japanese imperial expansion: the lines integrated industrial sectors, assured communications between the homeland and the colonies, and moved troops to trouble-spots and battle-fields. As in other empires, the railway lines that Japan built through its new territories were powerful symbols to its colonial subjects of technical superiority and political control; the United States occupying forces dissolved the imperial railroad companies immediately after Japan’s defeat in 1945. Yet in Japanese eyes the railways were valued not only as instruments of imperial power, but also because they extended Japan’s peaceful reach. The 1920s promotional postcard shown here, printed and distributed in London, declares that the South Manchuria Railway Company provides the “shortest and quickest route between the Far East and Europe.” Linking the country through Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway to Europe, it wove Japan into an international network of civilized and desirable destinations.

Credits

Photograph: South Manchuria Railway, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Post-card: South Manchuria Railway Co. Published by John Barnes & Co. Ltd, London, in the 1920s, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons