Short Teaching Module: Making Empire Global - British Imperialism in India, 1750-1800

Overview

The study of world history has often overlapped with scholarship on empire and imperialism. The global interactions engendered by empire have given rise to lively debate and even controversy about the nature of imperialism, its economic and political underpinnings as well as its impact on states, societies, and ecologies. This essay considers the beginnings of the British Empire in India and the relationship between imperial state formation and world history. It does so by examining how imperial agents and observers understood, debated, and shaped the increasingly global expanse of the British Empire. Thus, this essay highlights how global imperial connections were forged and emerged as subjects of contestation.

Essay

What do we mean when we speak of global empires? How exactly did global empires emerge and operate across vast distances, especially before the age of steam, telegraph, and the Suez Canal? What precisely was the relationship among the various geographies encompassed by a global empire? Did commerce make such empires global? Or was something more beyond the circulation of money and commodities such as spices and cotton textiles involved? The making of the British Empire in India during the second half of the eighteenth century offers a useful case study for examining the mechanics of global imperial expansion.

The English East India Company, established by royal charter in 1601, famously plied Britain’s trade with not only the South Asian subcontinent but also the wider world of the Indian Ocean, including the Persian Gulf and China. The English East India Company played a prominent role in establishing a commercial and political presence in burgeoning ports and urban centers such as Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras. Following major victories during the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), a global conflict fought against multiple rivals across three continents, the British presence in South Asia expanded far beyond coastal enclaves. This period of growing British territorial control and accompanying administrative expansion in the subcontinent has often been characterized as an era of “Company rule.” Given the vast geographic distance separating Britain and India, the actions of Company servants or so called “men on the spot” dominate both popular and scholarly accounts of colonialism in eighteenth-century India. The project of British imperialism in the subcontinent can thus appear to be a haphazard enterprise, one largely dictated by local contingencies and local actors. The opinions of British politicians back in London, Edinburgh, and Dublin seem to be of marginal significance in Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay. By the same token, events in India often seem peripheral to the major political dramas unfolding within Britain itself through the 1770s and 1780s. Therefore, despite the clear presence of British men, wealth and ships in India, the globalism of the British Empire can appear tenuous.

A consideration of even a handful of texts and images created across both eighteenth-century Britain and India can, however, challenge this commonplace perspective and illumine the profound connections between seemingly far-flung parts of the same empire. Indeed, historians are not alone in probing the precise nature of the relationship between Britain and India in the eighteenth century. Eighteenth-century British politicians, pamphleteers and even ordinary Britons and South Asians regularly interrogated and debated how this relationship might be conducted and transformed. Consider, for instance, this satirical print produced in London in 1788 [Figure 1]. Depicting a colossus-like figure standing astride two land masses and reaching out to the heavens, the print not only critiqued political hubris but also reflected on the momentous remaking of the relationship between Britain and the South Asian subcontinent through a recent parliamentary act. Titled “Dun Shaw, one foot in Leadenhall Street and the other in the Province of Bengal,” the print’s meaning can initially seem obscure to anybody unfamiliar with the daily rhythms of British politics and print culture. Nevertheless, the moniker “Dun Shaw” provides an essential clue by partially alluding to the name of the British politician and minister Henry Dundas, who served in the cabinet of the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger. “Shaw” or “Shah,” meanwhile, refers to the Persianate title for an Emperor commonly used by the Mughals as well as other ruling dynasties across Iran, Afghanistan, and India.

By combining Dundas’s name and the title of Shah, the printmaker sought to demonstrate Dundas’s conflation of domestic ministerial ambition with far broader imperial pretensions abroad. Furthermore, the printmaker chose to represent Dundas through a very specific sartorial combination: a turban and robe indicative of South Asian attire as well as a tartan kilt. While the partial depiction of Dundas in the garb of a South Asian ruler emphasized the minister’s status as a Shah-like figure, the tartan kilt highlighted Dundas’s Scottish identity and prominence in Scottish politics. That a critique of Dundas was partly articulated through a crude visual representation of his Scottishness points to the continuing tensions in the project of cultivating a shared British identity across England and Scotland in the decades since the Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707.

More importantly, for our purposes, the print showed Dundas trampling upon both Leadenhall Street, the location of the English East India Company’s headquarters in London, and Bengal, the site of the most extensive British territorial expansion in India since the 1750s. The print’s critique that Dundas had sought to impose his control on both the East India Company and the settlement of Bengal was not simply comic exaggeration. Indeed, the suggestion that Dundas had bridged the vast distance between London and Bengal through his person or political clout contained more than a kernel of truth. In 1784, the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger and Henry Dundas actively intervened in the governance of British territories in India by creating a new institution called the Board of Control for India Affairs through parliamentary legislation. Intent on sharpening their ability to control political and military affairs in India, Pitt and Dundas used this institution composed of serving ministers, including themselves, as a mechanism for vetting, drafting, and redrafting all official instructions dispatched to British officials in India. Moreover, to strengthen their ability to supervise events unfolding as far away as India, Pitt and Dundas appointed many of their ideological and partisan associates to positions of high office in the subcontinent. This included the appointment of Charles Cornwallis, a veteran of the American Revolutionary War, to the office of Governor General. Therefore, we can read this print as a pointed comment on growing ministerial control over both the East India Company and events in India.

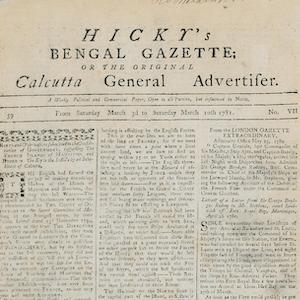

The print’s critique of Dundas’s outsize role implicitly alludes to the deliberate process through which imperial governance on a global scale was institutionalized. Clearly, individuals beyond Company servants on the ground in Bengal had a role to play in governing India. Beyond making visible the administrative circuits binding together disparate parts of the British Empire, this print’s production and circulation in Britain also gestures towards public interest in how precisely British India was being governed. As many other such prints from the 1780s [Figure 2] indicate, India was by no means a relatively peripheral part of Britain’s informal empire of trade, nor a marginal subject for British politicians and the British public. Rather, the question of India’s political future prompted fierce debate in the press and in Parliament and culminated in major legislative interventions throughout the 1770s and 1780s. Newspapers published in Britain as well as India reported on both mundane and momentous happenings across the global span of the British Empire. Hicky’s Bengal Gazette [Figure 3], one of the first English newspaper to be published in India, for instance, detailed British rivalries with the French in both the Indian Ocean and the Caribbean for a readership resident in Bengal. Taken together, such sources capture the makings of a global British empire, one connected by commodities as well as the flow of information, texts, official orders, as well as political satire and critique.

Primary Sources

Bibliography

Christopher A. Bayly, Indian Society and the Making of the British Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988).

K.N Chaudhuri, The Trading World of Asia and the English East India Company, 1660-1760 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978).

Thomas R. Metcalf, Ideologies of the Raj (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994).

Robert Travers, Ideology and Empire in Eighteenth-Century India: The British in Bengal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

James Vaughn, The Politics of Empire at the Accession of George III: The East India Company and the Crisis and Transformation of Britain’s Imperial State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019).

Credits

Tiraana Bains is a historian of South Asia, Britain and the British Empire. Her work examines how Britons and South Asians alike debated questions of empire, statecraft, labor and political economy. Her current book project, Instituting Empire: The Contested Makings of a British Imperial State in South Asia, 1750-1800, explains the emergence of a powerful British imperial presence in South Asia and the wider Indian Ocean world. Drawing upon English, Persian and Hindustani print and manuscript sources, this project demonstrates the regularity and density of contestation over the political futures of South Asia and the British Empire among an expansive cast of historical actors, from Bengali salt-workers and weavers to American colonists and Scottish parliamentarians. The project makes the case for thinking connectively about imperial state-building and institution-making across North America, the Caribbean and South Asia. Equally, it highlights the import of intra-imperial competition and collaboration among multiple British colonies across the Indian Ocean world. Bains is also researching a new project on the sharp divergences in the trajectories of various British colonial spaces such as Ireland and Australia between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries.