Long Teaching Module: Educational Reform in Japan (19th c.)

Overview

Soon after overthrowing the Tokugawa government in 1868, the new Meiji leaders set out ambitiously to build a modern nation-state. Among the earliest and most radical of the Meiji reforms was a plan for a centralized, compulsory educational system, modeled after those in Europe and America. Envisioning a future in which "there shall be no community with an unschooled family, and no family with an unschooled person," Meiji leaders hoped that schools would curb mounting social disorder and mobilize the Japanese people against the threat of encroaching Western imperialism. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

This long teaching module includes an informational essay, objectives, discussion questions, guidance on engaging with the sources, potential adaptations, and essay prompts relating to the nine primary sources.

Essay

Introduction

Soon after overthrowing the Tokugawa government in 1868, the new Meiji leaders set out ambitiously to build a modern nation-state. Among the earliest and most radical of the Meiji reforms was a plan for a centralized, compulsory educational system, modeled after those in Europe and America. Envisioning a future in which "there shall be no community with an unschooled family, and no family with an unschooled person," Meiji leaders hoped that schools would curb mounting social disorder and mobilize the Japanese people against the threat of encroaching Western imperialism.

The purpose of this module is to use the example of Japan to illustrate some key themes in the story of the rise of modern education: the connection between modern educational systems and the formation of the nation-state; the impact of European imperialism upon the spread of those systems; the increasingly inseparable association of "education" with "schooling"; and the accompanying impact of modern schooling upon the culture and social experience of childhood.

The Meiji government's decision to create a centralized school system can be seen in the context of two broad transformations in the concept and practice of education that have occurred worldwide in the last 400 years. The first is the widespread proliferation of educational institutions for commoners. This transformation occurred first in Western Europe and North America during the 17th and 18th centuries, when clergy and local elites, convinced that a limited education for local masses would have a positive effect upon the moral climate and the level of religious devotion in their communities, established schools for local children. Meanwhile, the expansion of the written word into the social and economic lives of ordinary people enabled them to conceive of the potential value of such schools.

This convergence of factors established the context for an unprecedented expansion in both school attendance and popular literacy. In England, France, New England, and parts of Germany and Italy, more than half of the male population, and over a quarter of the female population, had received some form of schooling and achieved at least a modest level of literacy by the end of the 18th century.

At that time, Japan was just beginning to undergo a similar transformation. However, a rapid increase in the number of schools enabled Japan to achieve comparable rates of school attendance and literacy by the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868.

While these changes were taking place in Japan during the early 19th century, a second transformation in education was underway in Europe and America. What defined this transformation was not a fundamental change in the number of schools or the patterns of attendance and literacy, but one in the organization and control of educational institutions. What we see, for the first time in history, is the systematic intervention of the state in the education of ordinary children.

Two key factors set the stage for this phenomenon. The first was the rise of industrial capitalism. Industrialization may or may not have stimulated a demand for education among the general population; however, what is clear is that the demographic shifts and social dislocations associated with industrialization begat new anxieties among elites about popular unrest.

Old fears about the danger of over-educated commoners gave way to the even more threatening specter of uneducated urban masses who lay outside the influence and regulation of social elites. Such concerns generated new ideas about how to prevent unrest through techniques of social management. Schooling came to be conceived as one of these techniques. Social elites, intellectuals, reformers, and government officials realized that the school could be used as a vehicle through which to properly socialize the lower classes—namely, to teach them discipline, frugality, and other values conducive to their new role in an industrializing society.

Another major development that formed the context for the intervention of governments in education was the emergence of the nation-state. This new political formation was premised on the active involvement of the entire population in the life of the nation. Governments at this time sought to integrate people into the institutions of the state, mobilize them for various kinds of service to the nation, and inculcate in them a personal identification with the nation. It was soon recognized that schools could facilitate these efforts.

Just as schools could prepare people for their new economic roles in an industrialized society, they could prepare people for their new political roles as participants in the nation-state. Schooling was therefore a task too important to be left uncoordinated. Nor could the responsibility for schooling be relegated any longer to local elites or the Church, who themselves constituted a threat to the power of the central government.

Thus the rationale of the nation-state required that governments assume an educative role, instructing people—particularly children—in values and habits conducive to building the strength of the newly-conceived national community. Childhood therefore became a window of opportunity during which the state could shape its citizenry and thereby strengthen the nation in an era of international competition.

By the mid-18th century, then, schooling in Western societies was closely bound up with industrial development and the emergence of a new kind of polity that relied upon the integration and mobilization of the masses. This was not lost on those Japanese who had opportunity to investigate conditions in the West. They had already discerned that the power of Western nations derived precisely from their industrial might and their ability to tap into the collective energies of their respective populations.

In the years following the Restoration, Meiji leaders also determined that widespread, centralized schooling would be essential if Japan were to harness these new forms of power for herself. Very early in Japan's state-building project, Japan's leaders hitched educational reform to the goals of strengthening the nation and protecting its independence; this much was agreed upon, even though officials diverged widely on many key aspects of educational policy. Much was riding on the creation of a new educational system, and as such, it became the nation's "urgent business" (kyūmu)—one of a number of terms that would be repeated endlessly by local officials during the early years of educational reform.

While the public educational systems in mid-19th century Europe and America represented the cumulative product of several phases of interventions by the state, in Japan the urgency of this task would not allow for such a fitful process. Rather, the creation of a new educational system would be attempted in one sudden, systematic, sweeping intervention.

Primary Sources

Teaching Strategies

Strategies

While this module is part of a larger project on the history of youth and childhood, the sources deal mainly with the history of schooling and education. More narrowly, they deal with the issues faced by a single country—Japan—as it attempted for the first time to establish a national education system. For this reason, instructors should be prepared to help students make connections between the specific sources in this unit and the larger issues relating to the history of youth and childhood.

First, instructors may need to make explicit the connection between the history of childhood to the history of schooling and education. The connection may seem self-evident: after all, childhood is the stage of life when people go to school and receive an education. However, this has not always been the case. For the overwhelming majority of people, and for most of human history, formal schooling has not been a part of the experience of childhood.

The sources in this unit focus precisely on the moment when the Meiji government, in its efforts to modernize the Japanese nation, sought to make schooling an essential part of being a child. Furthermore, it is in large part through modern schooling—through the exercise of moving children out of the home and into a distinct institution charged with their care—that childhood as we know it has been defined. Instructors using these sources should try to point out this larger context, to help students to understand that their automatic association of childhood with schooling was something that has not always existed, and that these sources come from a time when it began to exist.

Second, students may require some assistance in placing the case of Meiji Japan in a global historical context. As I discuss in the introductory essay, there are two larger contexts in which Meiji-era education can be understood. First, it is an example of the initial efforts by modernizing governments to intervene in society's efforts to educate children by creating compulsory, state-run school systems. This is a relatively recent phenomenon, dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, and the case of Meiji Japan should be seen as part of this larger historical movement.

Third, many of the sources in this unit can be best understood within the context of the history of Western imperialism. While several of the sources in this unit reveal an enthusiasm for Western models of schooling, it is important to remember that the specter of imperialism loomed behind all discussions of childhood and education. Japanese leaders understood that the adoption of Western models for schooling were part of the effort to overturn unequal treaties and prevent future incursions upon Japan's sovereignty. The context of imperialism, in turn, helps us to understand how the issues of childhood and education get wrapped up in discussions about tradition and national identity. Efforts to model Japan's education on the example of the West—the very nations that Japan perceived as threats—naturally spurred anxiety about the loss of tradition. Discussions of schooling and childhood—like discussions of gender, for example—were often proxies for discussions about tradition, modernity, imperialism, and national identity.

Discussion Question

To help draw out these contexts, instructors might want to ask questions that encourage students to connect these sources to larger issues in the global history of childhood. For example:

- What kinds of ideas about the purpose of education would not lead to the creation of school systems?

- How do you think the onset of compulsory schooling changed the experience of childhood? (A more informal, personal version: How would your life be different if schooling were not a part of it?)

- What motivations might governments have for investing so much effort into creating systems of education? What kinds of obstacles might governments face in attempting to do so?

- Why do you think that children might have become so important to governments beginning in the 18th and 19th centuries? How does the issue of childhood reflect larger questions about national identity?

- How do you think the debates about education and schooling we see in Meiji Japan might have played out differently in 19th-century Europe and the U.S.?

Lesson Plan

by Susan Douglass

Time Estimated: two to three 45-50-minute classes

Objectives

- Explain the relationship between modernizing the Japanese education system and Japanese nation-building.

- Explain the identification between education and schooling in the modernizing state.

- Assess the impact of modern schooling on Japanese culture and changes in children's lives.

- Analyse the impact of European imperialism on the decision-making process regarding educational reform.

Materials

- Printouts of primary sources sufficient for each student to have a full set of the texts and images in the Educational Reform in Japan (19th c.). 1

Day One

Hook

Compare the two images of Terakoya vs. Meiji School. Jot down a list of characteristics that describe the first school and th e second one. How does the nature of education seem to have changed? Which one would you rather attend, and why? What may have been lost and gained in the process of change?

Making Sense of the Sources

The most difficult task in using this teaching module is differentiating among similar ideas expressed in the written documents, and matching them with the various quarters of society in which they originated. It is necessary to identify the voice (traditional elements, progressive modernizers, state officials) and record their keywords and viewpoints, the outlines of debates and issues, tensions between the need to reform and the need to preserve, the social tensions and practical issues involved. Use the graphic organizer to collect and summarize ideas expressed in the documents about the nature and purpose of education in Meiji Japan, filling in the chart as an individual or small-group activity. Debrief after filling out the chart, discussing the change in the subjects, objects, and purposes of education these writers contemplated or realized. Finally, what evidence do the documents present concerning the sources of pressure to change the education system?

Use the Kaichi and Mitsuke Schools image to describe the physical setting of the modernized schools, including the second and third of the series of classroom images in Terakoya vs. Meiji School. Discuss the change from traditional education to modern education in light of what the documents reflect of Japanese intellectuals' and officials' vision of a modernized Japanese society. How do the school buildings reflect both traditional Japanese and Western influences?

Day Two

How do you think this new form of education affected children in rural and urban areas? How did it change the position of the child among adults, and the family's and the child's relationship to the state?

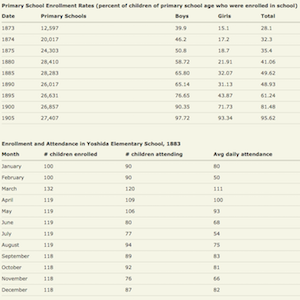

Using the image of rural children together with the attendance table, identify the obstacles and challenges to instituting universal schooling in Japan. Identify documents in the group that discuss difficulties to attaining education among the various classes. Compare these problems with contemporary challenges to school attendance and parental involvement in your own school and in contemporary discussions of education reform in the media.

Ask students individually or in groups to come up with an additional type of document or information set that would help clarify the issues raised in the document based question. [For example, the documents reveal nothing about the proposed curriculum for these schools, to answer the question of balance between traditional learning and modern learning, academic subjects vs. practical /vocational learning and the arts. This is especially interesting in the case of Japan, whose educators were more attentive than some modernizing states to traditional arts and crafts, for example.]

Day Three

The culminating activity is writing the DBQ essay, which can be done as an outside assignment or a timed activity, at the instructor's discretion. In the latter case, this would add one class period to the length of the activity.

Differentiation

Advanced Students

Students may research additional information on Japanese schooling during the Meiji period, such as curriculum and images of textbooks, narratives about school days from literature and film, for example.

Less Advanced Students

Remedial students can focus on a more limited range of documents and themes and could be given a modified question that of more limited scope. Alternatively, they can be given more time and scaffolding to help identify the issues. A small-group activity, for example, would have each student become very familiar with just one of the documents, and represent that voice and point of view in a panel discussion role-playing a debate among Japanese policy-makers on how to reform the schools. Their preparation could be supported by reading textbook summaries on the social history of Japan during that period, in order to identify the various interest groups and associate them with the positions taken in the documents.

1 Texts include:

- Emperor Meiji to President Grant on Iwakura Mission, 1871 [Letter]

- Preamble to the Fundamental Code of Education, 1872 [Government Document]

- Encouragement of Learning, 1872 [Literary Source]

- Terakoya vs. Meiji School [Images]

- Meiji Era School Attendence [Tables]

- Kaichi and Mitsuke Schools [Images]

- Imperial Rescript: The Great Principles of Education, 1879 [Official Document]

- On Education [Essay]

- "The Imperial Rescript on Education" [Official Document]

- Two Girls Carrying Children [Photograph]

- Explanation of School Matters [Official Document]

Document Based Question

by Susan Douglass

(Suggested writing time: 45-50 minutes)

Using the images and texts in the documents provided, write a well-organized essay of at least five paragraphs in response to the following prompt.

- Based on analysis of evidence in the documents, assess the importance in Meiji Japan of developing a system of universal education as a requirement of nation-building.

Include in your discussion evidence of:

- leaders' and intellectuals' views on the purposes and goals of education,

- elements identified as needing change in Japanese society, and the obstacles to achieving it,

- justifications for achieving educational goals by establishing universal, compulsory education, and

- the sources of motivation for reforming education and the models on which the new education system would be based.

Your essay should:

- have a clear thesis,

- use at least six of the documents to support your thesis,

- show analysis by grouping the documents into at least two groups,

- analyze the point of view of the documents, and

- recognize the limitation of the documents before you by suggesting an additional type of document or source to make your discussion more complete or valid.

Bibliography

Credits

About the Author

Brian Platt is an Assistant Professor of History at George Mason University. He is the author of Burning and Building: Schooling and State Formation in Japan, 1750-1890.

About the Lesson Plan Author

Susan Douglass is a doctoral student in history at George Mason University, and also serves as education outreach consultant for the Al-Waleed Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding at Georgetown University. Publications include World Eras: Rise and Spread of Islam, 622-1500 (Thompson/Gale, 2002), the study Teaching About Religion in National and State Social Studies Standards (Freedom Forum First Amendment Center and Council on Islamic Education, 2000), and teaching resources, both online and in print, including and the curriculum project World History for Us All, The Indian Ocean in World History, and websites for documentary films such as Cities of Light: the Rise and Fall of Islamic Spain and Muhammad:Legacy of a Prophet.

This teaching module was originally developed for the Children and Youth in History project.