Letters of Philip II, King of Spain, 1592-1597

Students who are interested in European history will surely know of the 1588 defeat of Spain’s fleet of ships, her Armada, at the hands of the English and bad weather. The best account of the battle is Garrett Mattingly’s classic, The Armada; a more recent account by David Howarth is also quite serviceable. But, your fledgling historians may ask, what happens to Spain—and to the Spanish fleet—after this battle? This site offers at least a partial answer with an online collection of 153 letters in Spanish from King Philip II to Diego de Orellana, his representative on the northern coast, and others, penned between 1592 and 1597.

The first letters, in 1592, concern the construction of 12 galleons, known as the Twelve Apostles. A letter from 1594 (7 March 1594) gives Captain Domingo de Villota the right to privateer against the English and the Dutch.

If we turn to the letters of spring 1595, we see the king concerned that a fleet be assembled quickly, but with plenty of experienced sailors on board. And how might one find willing sailors for such a project? Philip, known in Spain as Philip the Prudent, suggests to Diego de Orellana (10 Feb 1595) that he might tell prospective sailors that they will be very well treated, paid punctually, and that they’ll be given permission to return home when the fleet winters over. It’s not too difficult to imagine, reading Philip’s words, what some of the typical problems were for sailors of the time.

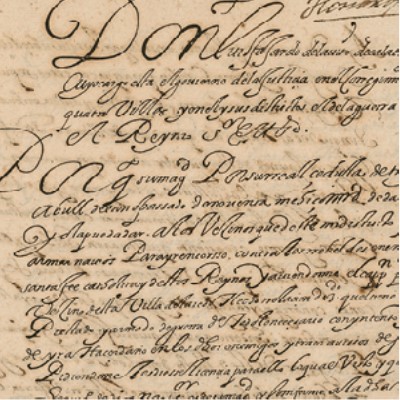

The collection is presented digitally in admirable fashion. The letters, grouped by the year in which they were written, are offered in a clear, readable facsimile. This is not always the case with primary sources online. The collection at U.C. Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, for example, occasionally provides an image of the document instead of a legible copy to work with.

This site, on the other hand, provides not only a readable image, but a transcription for each letter as well, for those whose paleography is not yet up to the challenges of the 16th century. Navigability is excellent, as indeed it ought to be on so nautical a site. Switching between facsimile and transcription, or traveling forward or back, is an option offered at the foot of each page.

Alas, there is no translation in English available on the site, although there are summaries for each letter in English. Thus, students who wish to work with these documents should be both confident of their Spanish and imaginative enough to puzzle out 16th century abbreviations and phrases. Though challenging, it might be an interesting project for third-year Spanish students.

This correspondence between the king and his representatives in the north may interest those intrigued by the politics of the 16th century, but high-school students who imagine sailing the high seas may find Carla Rahn Phillips’ Six Galleons for the King of Spain—which discusses the construction and outfitting of some of the galleons for the Armada—much more interesting.

For those who want more, Professor Phillips’ new translation of Pérez-Mallaína’s work, Spain’s Men of the Sea, will give students an idea of life aboard the ships that made the Atlantic crossing in this time. Who knows? Perhaps these works in English, and some encouragement from their Spanish teachers, will have them puzzling out this site’s online transcriptions of Philip II’s letters—and even attempting the original paleography!