Letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu

Annotation

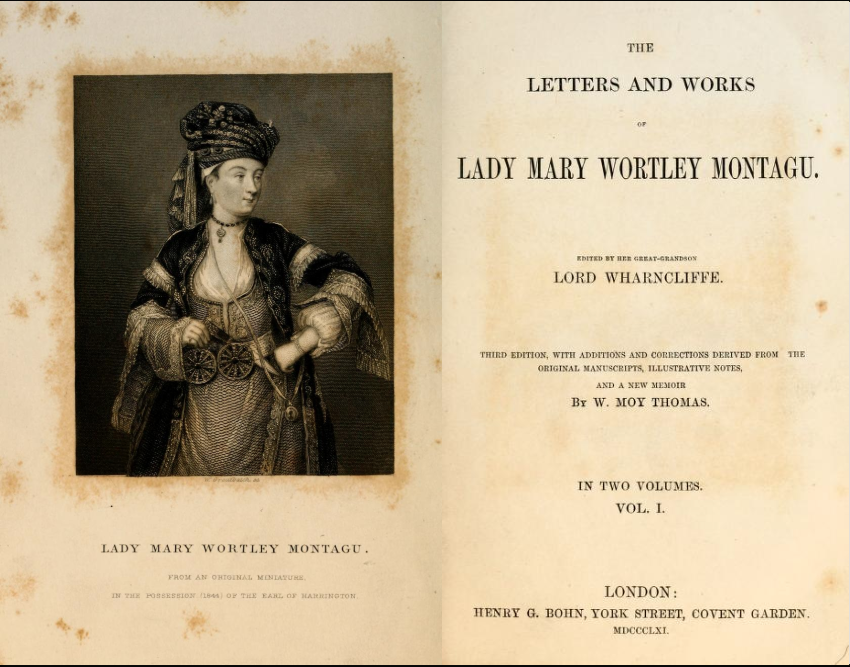

The following are excerpts from the letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), a noted English essayist and one of the earliest advocates of women’s rights. She is perhaps best known for her letters from Constantinople, which she wrote to various friends and family members while living abroad with her husband, Lord Edward Wortley Montagu, the British Ambassador to the Ottoman court from 1717 to 1719. Lady Montagu’s letters demonstrate a keen interest in Turkish customs, particularly those relating to women. She was clearly intrigued by the differences between her own sensibilities—and ideas of propriety—and those of Ottoman ladies. She wrote extensively on those differences, always remaining open-minded and conscious of the cultural differences that explained otherwise “weird” behavior. Her commentaries serve to paint simultaneously a picture of European woman’s views of the world and those of their Turkish counterparts, as mediated by a contemporary woman.

This source is a part of the Women in the Early Modern World, 1500-1800 teaching module.

Text

To the Countess of ____.

Adrianople, April 18, O.S. [1717]

. . . I was invited to dine with the Grand Vizier’s lady, [the Sultana Hafitén, favourite and widow of the Sultan Mustapha II., who died in 1703] and it was with a great deal of pleasure I prepared myself for an entertainment which was never given before to any Christian. . . . I chose to go incognito, to avoid any disputes about ceremony, and went in a Turkish coach, only attended by my woman that held up my train, and the Greek lady who was interpretress. . . . In the innermost I found the lady sitting on her sofa, in a sable vest. She advanced to meet me, and presented me half a dozen of her friends with great civility. . . . The treat concluded with coffee and perfumes, which is a high mark of respect; two slaves kneeling censed my hair, clothes, and handkerchief. After this ceremony, she commanded her slaves to play and dance, which they did with their guitars in their hands . . .

I . . . would have gone straight to my own house; but the Greek lady with me earnestly solicited me to visit the kiyàya’s lady, [the wife of the Grand Vizier’s lieutenant] saying hers was the second officer in the empire, and ought indeed to be looked upon as the first, the Grand Vizier having only the name, while he exercised the authority… All things here were with quite another air than at the Grand Vizier’s. . . . I was met at the door by two black eunuchs, who led me through a long gallery between two ranks of beautiful young girls. . . . I was sorry that decency did not permit me to stop to consider them nearer. . . . On a sofa, raised three steps, and covered with fine Persian carpets, sat the kiyána’s lady . . . and at her feet sat two young girls, the eldest about twelve years old, lovely as angels, dressed perfectly rich, and almost covered with jewels. . . . She stood up to receive me, saluting me after their fashion, putting her hand upon her heart with a sweetness full of majesty, that no court breeding could ever give. . . . Her fair maids were ranged below the sofa, to the number of twenty, and put me in mind of the pictures of the ancient nymphs. . . . She made them a sign to play and dance. . . . This dance was very different from what I had seen before. Nothing could be more artful, or more proper to raise certain ideas. The tunes so soft!—the motion so languishing . . . that I am very positive the coldest and most rigid prude upon earth could not have looked upon them without thinking of something not to be spoken of.

To the Lady ____

Belgrade Village, June 17, O.S. [1717]

. . . I am afraid you will doubt the truth of this account, which I own is very different from our common notions in England; but it is no less truth for all that.

If one was to believe the women in this country, there is a surer way of making one’s self beloved than by becoming handsome; though you know that’s our method. But they pretend to the knowledge of secrets that, by way of enchantment, give them the entire empire over whom they please. For me, who am not very apt to believe in wonders, I cannot find faith for this. I disputed the point last night with a lady, who really talks very sensibly on any other subject; but she was downright angry with me, that she did not perceive she had persuaded me of the truth of forty stories she told me of this kind; and at last mentioned several ridiculous marriages, that there could be no other reasons assigned for. I assured her, that in England, where we were entirely ignorant of all magic, where the climate is not half so warm, not the women half so handsome, we were not without our ridiculous marriages; and that we did not look upon it as any thing supernatural when a man played the fool for the sake of a woman. But my arguments could not convince her, . . . though, she added, she scrupled making use of charms herself; but that she could do it whenever she pleased. . . . You may imagine how I laughed at this discourse; but all the women here are of the same opinion. They don’t pretend to any commerce with the devil; but that there are certain compositions to inspire love. If one could send over a ship-load of them, I fancy it would be a very quick way of raising an estate.

To the Countess of ____

Pera of Constantinople, March 10, O.S. [1718]

I went to see the Sultana Haftén, favourite of the late Emperor Mustapha. . . . The Sultana seemed in very good humour, and talked to me with the utmost civility. I did not omit this opportunity of learning all that I possibly could of the seraglio, which is so entirely unknown among us. She assured me, that the story of the Sultan’s throwing a handkerchief is altogether fabulous; and the manner upon that occasion, no other but that he sends the kyslár agá, to signify to the lady the honour he intends her. She is immediately complimented upon it by the others, and led to the bath, where she is perfumed and dressed in the most magnificent and becoming manner. The Emperor precedes his visit by a royal present, and then comes into her apartment: neither is there any such thing as her creeping in at the bed’s foot. She said, that the first he made choice of was always after the first in rank, and not the mother of the eldest son, as other writers would make us believe. Sometimes the Sultan diverts himself in the company of all his ladies, who stand in a circle around him. And she confessed that they were ready to die with jealousy and envy of the happy she that he distinguished by any appearance of preference. But this seemed to me neither better not worse than the circles in most courts, where the glance of the monarch is watched, and every smile waited for with impatience, and envied by those who cannot obtain it.

TO THE COUNTESS OF _____

. . . Turkish ladies . . . are perhaps freer than any ladies in the universe, and are the only women in the world that lead a life of uninterrupted pleasure exempt from cares; their whole time being spent in visiting, bathing, or the agreeable amusement of spending money, and inventing new fashions. A husband would be thought mad that exacted any degree of economy from his wife, whose expenses are no way limited but by her own fancy. ‘Tis his business to get money and hers to spend it: and this noble prerogative extends itself to the very meanest of the sex. Here is a fellow that carries embroidered handkerchiefs upon his back to sell, as miserable a figure as you may suppose such a mean dealer, yet I’ll assure you his wife scorns to wear anything less than cloth of gold; has her ermine furs, and a very handsome set of jewels for her head. They go abroad when and where they please. ‘Tis true they have no public places but the bagnios, and there can only be seen by their own sex; however, that is a diversion they take great pleasure in.

Credits

Montagu, Mary Wortley. The Letters and Works of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu. Volume 1. Edited by her great-grandson Lord Wharncliffe. London: George Bell and Sons, 1887.