Analyzing Oral Histories

Overview

The modules in Methods present case studies that demonstrate how scholars interpret different kinds of historical evidence in world history. This module is based on a series of oral history interviews conducted in the mid-1990s. The interviewees were Palestinian women who grew up under the British Mandate and were active in the Palestinian Women’s Movement. Analyzing the interviews offers an important look at the lives of these women, who were often educated and very active in their communities, and at the process of working with oral history. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

Video Clip Transcripts:

1. What kind of source is this?

This was an interview with a lady named Sa’ida Jarallah done in the spring of 1994. At the time, she must have been in her early 70s. She was one of the first Palestinian Muslim women to study abroad in the 1930s. This is an interview about her life, about social and cultural aspects of growing up as a young female in the 1930s in British Mandate Palestine. Right after World War I, much of the Arab Middle East was divided into mandates that were granted to the British and the French by the League of Nations. In what became Israel later on, the territory of Palestine was granted to Great Britain. The mandates were supposed to be a training period for the Arab countries of the Middle East to eventually become independent. In the case of the Palestinian Mandate, this was not clear. Written into the mandate was the Balfour Declaration, which granted permission for the Jews to establish a “national home” in Palestine. There were contradictions as to protecting the rights of what they called the non-Jewish population, the Arabs (mostly Muslims, some Christians), and the rights of a burgeoning nationalist Zionist movement. The period is about 1920 to 1948, and most of the young women of the middle or upper classes who were educated did not go abroad. Sa’ida Jarallah went to England. And in the time period and society we’re talking about, that was something that broke with tradition. Sa’ida Jarallah was doubly daring and innovative because she actually went to a Christian country, and the country of the occupiers, and studied there. These young women were self-conscious about the fact that they were pioneers, which is a word that they actually used in the literature often. And they were very aware of the fact that they had to be extra careful as young Muslim women in a society that restricted women’s mobility and roles. They had to be careful not to do things that would jeopardize those who came behind them. She says: When I left to England I was only eighteen. I finished school early and got a scholarship to study in England. My mother told me she worried about sending me but that she couldn’t prevent me. She said that if something happened to my reputation then I would ruin things for my six sisters. She was worried about me because I was not used to talking to men and to come and go as I wish. I never forgot her tears and her tears made me be careful with whom I talked and with whom I visited. This was a very long time ago, in 1938.Video Clip Transcripts:

2. What were the social and political experiences of women in Palestine?

The political movement in Palestine was volunteer. The leadership ended up mostly being single women because most of the women involved in the movement were married, had family responsibilities. They funded it themselves. They weren’t working-class women who were burdened with jobs. They had more leisure. Many of them had some household help, for example. That being said, they were extremely active during certain periods. They were formally organized. Sa’ida Jarallah was not one of the major leaders of this movement. She ended up being an educator, and most of her sisters and sisters-in-law were as well. And this was one of the major respectable areas for a woman of that class to work. Many of these young women were not educated towards any career. To be educated in the context of this place and time had a very specific connotation. Being educated meant more than actually having an education. It meant being of a certain mindset. The word that people used in referring to these women was muthaqqafat, which comes from the word for culture muthaqaffa. There was not a lot of difference in the experience of Muslim and Christian women of this generation. The common tie, which many of them spoke about, was the fact that they were educated at the same schools. One woman even mentioned how she felt that the fact that they were all educated together created a sense of common bond and culture. We never felt the difference. We were all the same. We were educated and never felt any difference but the old generation used to differentiate between both Christians and Muslims. We used to live together in boarding schools and in the training college and as members of the same associations. Miss Wahbi, [who was a Christian educator in Palestine during the Mandate period], was my teacher in the training college and her sister Sofi taught me in Schmidt [another school]. We lived together like sisters and never felt any difference. We used to love each other.Video Clip Transcripts:

3. What are some strengths and weaknesses of oral histories?

Many times, when I went to an interview with an idea of the kind of information that I wanted, the people I was interviewing took control of the interview. And what is interesting to emphasize is what it seems to tell about the person. What do they focus on? If you ask them a question that seems straightforward, what kind of tangents do they get off on? What does this tell us about what is important about their history to them? Particularly with oral history, you have to go into it with a much more open mind than we often are trained to do as formal historians. This happened to me in almost every interview I did, and I did about 70 of them. I went into these interviews wanting to ask women about the organizations that made up the Palestinian women’s movement during the British Mandate period, about leaders, activities, individuals. I would ask questions and the women would say something simple or dismissive or say, “Well, I don’t know that much about this, but when I was 16 . . .” and then they’d launch into discussing other things. I thought I was going to write a book about the Palestinian women’s movement. And I did. But I ended up writing a lot about women’s education and women’s lives and the status of young women of a certain class during the Mandate period. And it was people like Mrs. Jarallah who contributed to constructing a picture of that time that I had not thought out myself. They tutored me indirectly about certain topics that meant things to them. And one of the big themes that emerged was education. These were women who were very proud of being educated. It was extremely significant to them in a way that I didn’t immediately recognize. Language is always an issue, because I interviewed people in both Arabic and English. In some cases, women liked to show off their English. In other cases then, you have the intermediary of translation. When people are speaking in the language they’re more comfortable in, they’ll talk more fluidly. When I first started interviewing, I used certain language that I had learned as a grad student in Arabic that people didn’t use. For example, the word for mandate in Arabic is intidab. I’d go in and say I wanted to talk about al intidab al britani, which is a British Mandate, and people would look at me as though I was speaking Japanese. They said things like “When the English were here,” or “Under the English”, taht al ingliz. One of my obstacles was to learn not to talk so formally. Everybody who does oral history has these same kinds of sets of issues, and they’re not easily overcome. Women’s hesitation, the issues of women not thinking of themselves as worthy narrators of history, the problem of concepts of history, (my concept, their concepts, men’s concepts, women’s concepts).Video Clip Transcripts:

4. What factors shape an oral history interview?

Being a younger woman talking to older women, too, I ended up being perhaps overly deferential and allowing them to control the interviews. When you’re dealing with human sources, human beings, and human interactions, I think it’s very difficult to make it a science. You can’t anticipate what it’s going to be like—facial expressions, chemistry with people. In my case, it was very important to interview women without men where possible. You frequently would have men censoring the women or trying to take control of the interview. There are subjects they would discuss with a Palestinian woman that they wouldn’t discuss with me, and I think subjects they would avoid with a Palestinian woman that they talked to me more about. In some respects, politically, they were freer to talk to me. When it came to issues that they didn’t want to show to the outside world, there were certain issues they might have avoided. Talking about sexuality isn’t as big a deal as one might imagine, particularly for older women who are poor or peasant women. They have a much more practical sense of birth, death, sexuality. The identity of the interviewer, as long as it’s a woman, may not be such an issue. In the rural areas, people would talk about stories that they had heard. Specifics are not known, things are not written down. It’s more a part of collective memory. So that I had different responses according to who I was interviewing. Sometimes there was an avoidance of questions. There was one issue which was a bit sensitive. In the Mandate period in Palestine, there was incredible tension between two factions associated with two major notable families in Palestine, the Hussani family and the Nashashibi family. It was indirectly responsible for why the Palestinian Nationalist movement was not strong enough to meet confrontations against the Zionist movement. And the women’s movement started out as one women’s organization. In the 1930s, it split into two factions. It was not as contentious and not as tense as it was in the male-led nationalist movement. And yet women tried to avoid discussing it, partially, I think, because they wanted to project unity from this period. People outright denied that this existed or talked about it in a way which was very sensitive. On other levels, the older Palestinians were eager to talk about the past. When we got talking about the late 1940s, people broke down. And in one case, a woman was so upset about what happened to the Palestinians in 1948 that she wouldn’t talk at all. Some people would refuse to talk just out of sadness. It had nothing to do with me personally. These were obstacles. The time I interviewed was before the Oslo Accords. The Israelis militarily occupied the West Bank and people were fearful of a strange person asking questions. It didn’t prove to be a major obstacle because I had lived in Palestine before. I spoke Arabic. I had friends accompany me. And I started cultivating a network. It wasn’t too difficult because I was talking about events that happened, at that time, 60 or 50 years earlier. One quote I got frequently is, “Why are you talking to women? They didn’t do anything. Talk to the men.” People tried to steer me toward men. When I wanted to talk to ordinary people, they often tried to steer me toward people who were well known, who were in the contemporary political scene and had nothing to do with my topic.Video Clip Transcripts:

5. How do students analyze Sa’ida Jarallah’s interviews?

In this quote, she talks about her father, a highly placed judge in the Islamic court system in Jerusalem. He’s a recurring theme in the interview—how he helped her and her sisters become educated. My father was in the Shari’a [Islamic law] court; later he became a mufti [which is a high position]. That’s why people used to blame my father for allowing us to study in Catholic schools and sending us to finish our education abroad. His job required him to be consistent with the Islamic Shari’a and not allow his daughters to do as they wish. But he used to trust us and love and respect us, and never did anything to disappoint us. My father believed in educating women. He would say that a woman should have her diploma as a bracelet in her hand. For if she did not get married or married but was widowed or divorced, she should be independent and have her own job and life and not depend on her father or brother to support her. We were seven daughters and he was always worried that we should be able to provide for ourselves. I asked her, “Why wasn’t your father against the idea of educating his daughters?” She said: “That’s just the way he was. He believed in educating women.” She doesn’t really have an explanation for that, but this is one way of reading the source. He had seven daughters and one son. You can see why he might be concerned about women’s education, about his daughter’s future. If a student were to use this, it seems somewhat straightforward. It talks about her father supporting education, supporting these girls. In fact, there’s some cultural even Islamic codes in here. He said that a woman should have her diploma as a bracelet in her hand. This has a specific Islamic context to it. When women marry, they receive a dowry from the husband. And it’s a very important part of Islamic law, the fact that women receive their own property, which is not conjugal property. Traditionally, in Palestine and in much of the Arab East, the form that the dowry has often taken has been valuable jewelry, such as a bracelet. So when he says it’s a bracelet in her hand, it’s a symbol of security and economic independence. That dowry belongs absolutely to a woman. Part of the dowry is deferred until the end of the marriage. If the woman was divorced, then the deferred dowry is owed to her. If the husband dies, one of the first aspects that is settled is the deferred dowry. If a woman is divorced or if her husband dies, she usually goes home to either her father or a brother. This is a very strong statement about her father and how he really believed in the independence of his daughters in a time period when this was highly unusual.Video Clip Transcripts:

6. What do students learn from this oral history?

Most American students dealing with the Middle East have stereotypes. When I prepare them to read this, I try to get them to look for what might surprise them. And I try to get them to look at issues of reading it from the outside going in. What kind of ideas did they have about a young Muslim woman in the 1930s in a country like Palestine? How does this interview deconstruct these preconceptions? What kind of personality can they sense here? I tell them to pay attention to language. This is a little difficult because they’re reading it in translation. I ask them to look at how it is that the person responded to questions and the way that people shape their own narratives in an interview—the fact that they emphasize certain things, or that they stray off into another topic. And I ask them to think about what that means and how to interpret that. I prepare them for the fact that this is very different from reading, for example, a diplomatic document. It gives you a sense of everyday people. Students respond much better to these kind of sources. They’re fascinated. They remember more about them. The things that they notice are very different often than what I notice. There’s another section that strikes them. It’s about wearing the head scarf called hijab in Arabic. I asked “What did you used to do as young girls?” She says: We used to go to the cinema at the holidays. My father did not mind us going but my mother was against it and did not like us to go. But we did anyway. There were beautiful old movies. I remember seeing Gone With The Wind three or four times. Sometimes my mother and father used to go with us and my father used to explain the movie to us. My father was more like the foreigners. They used to blame my father for letting us do as we wished. This is a favor my sisters and I will never forget from our father for as long as we live. He was honest to us. He loved us and respected us and treated us like real women. And those days, people still wore the hijab [the Islamic head scarf]. People used to look differently at me when I rode the bus to the Training College. I used to be wearing nice clothes. Men used to look at me differently because I was not wearing the hijab. Once I was riding the bus and an old woman wearing the hijab recognized me. She said to me, “Sa’ida, why are you not wearing the hijab? Do you think when you get married that your husband will allow you to go out without the hijab?” I answered her in front of all the men on the bus. “If Shaykh Hussam gave me the permission to go out without the hijab then there is no one in the world that can force me to wear it.” What strikes the students is how a Muslim man, her father, was more liberal than her own mother, a woman. And how an old woman on the bus was the one who criticized her. It makes them rethink their stereotypes about Muslim men as opposed to just Muslim women. It gives you a sense of gender, not just women. They recognize that, in fact, Muslim men were not oppressing women, which is how they tend to think about men in Islam. Once I get them to recognize how this interview destroys their stereotypes, they have to understand this interview with an overall historical context. There were Muslim men who supported female education, and there were Muslim women who were educated and had opportunities. And yet they have to situate this individual within the broader historical context. This was an exceptional woman. Students have this tendency to take a source and then generalize everything from it. So once they get into it from the inside out, then they have to go from the outside in and recognize it as a unique source. What’s very difficult is to understand these subtleties, to not overly generalize either from the perspective of stereotyping all Muslim people in the Arab world or from exceptionalizing or having this distorted version of what people are like. This shows them the complexities of this world.Download Full Video Transcript

Primary Sources

Credits

Ellen Fleischmann received her PhD from Georgetown University and is Associate Professor of History at the University of Dayton. She is author of The Nation and its "New" Women: The Palestinian Women's Movement, 1920-1948, and has written numerous articles on women in the Middle East.

Grateful Acknowledgement is made to the following institutions and individuals for permission to publish material from their collections:

Aziz al-Azmeh, Private collection

Orayb Najjar, Palestine Exploration Fund

Walid Khalidi, Before Their Diaspora: A Photographic History of the Palestinians,1876-1948 (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1991), and the

Institute for Palestine Studies, http://www.palestine-studies.org/

For:

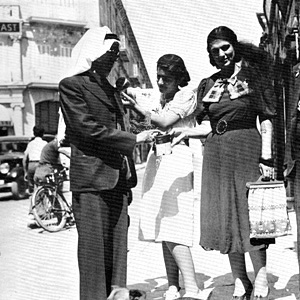

- Palestinian women, Jerusalem, 1930s

- Jerusalem Girls’ College, c. 1920

- Fundraising for Palestinian families, Jerusalem, 1936

- Boarders at Schmidt Girls’ College, Jerusalem, 1947

- Schmidt Girls’ College, Jerusalem, 1947

- Palestinian conference, 1930

- Palestinian Delegation, London, 1930

- Prominent Muslim family, Jaffa, c. 1925

- Palestinian village family, 1927

- Muslim wedding, near Ramleh, 1935

- Palestinian students, London, 1928