Analyzing Newspapers

Overview

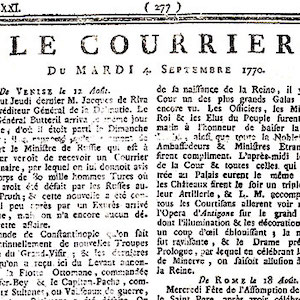

The modules in Methods present case studies that demonstrate how scholars interpret different kinds of historical evidence in world history. In the video historian Jack Censer analyzes an 18th-century French newspaper, Le Courrier d’Avignon, and an image of the reading public in France around the same time. By the late 18th century, newspapers had become important means of communication in France, England, and other countries. Papers like Le Courrier d’Avignon had correspondents in many cities and reported on both domestic and international news. Newspapers offer an important window into the past, but to understand them as a historical source, it is important to look at the newspaper, competing newspapers, literacy, and to ask how people read newspapers in different times and cultures. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

Video Clip Transcripts:

1. What are some of the challenges of reading a newspaper?

These are the front sections of the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Washington Times for Monday, May 19th [2003]. The most important thing, actually, that if you just took a look at the paper and if the paper were laying open, each one of them has a non-political story. The front page is traditionally a political medium. Over time, the American press has made more and more space on the front page for non-political stories. The Washington Times, right in the center of its page, even above the fold, has a story on a woman who puts her head in the mouth of a crocodile. The New York Times has a picture of a baseball at San Quentin. And then an article on hackers in the Washington Post. This [treating non-political stories] is something that journalists think now they need to do. They need to appeal beyond the political, and these are three large color pictures in the center of the page. The New York Times and the Washington Post are more discreet; they’re below the fold. And that’s important when you realize that at newsstands and in machines, below the fold doesn’t show. Let me talk about the most interesting contrast [between the New York Times and the Washington Post]. Their main story, in the middle of the page, with exactly the same picture, although cropped differently, is a story on the problems in establishing civil authority in Iraq. Fundamentally, they give different reasons for why there are problems in post-war Iraq, why things aren’t working. The New York Times story focuses on the failure of General Garner and his subordinate bureaucracy. If we turn in to the Washington Post, we find no mention—virtually no mention [department of defense]—of General Garner’s failings at all. The explanation here turns largely on Donald Rumsfeld. Despite the fact that they featured the same story and their editors put it on the front page—the editors used the same photograph by the same person, Murad Sezer working for the Associated Press—in the end, if you read the story, they have totally different takes on why things are falling apart. One chooses an individual, one chooses basically a bureaucracy. What’s interesting here is not this individual story, but just imagine that, if over time, the New York Times generally ascribed failures to individuals, and the Washington Post generally ascribed failures to bureaucracies, one could have a whole different world view of how things work or don’t work. And that’s what a historian has to do. You have to tease out the meaning of every story, but you can’t take too much in any story because any individual story could, in fact, be anomalous. Now to turn to the Washington Times. I don’t actually have to pick up the paper, I can see from here they don’t cover the story. And if you go through the entire paper as I did, looking page by page, there’s nothing on this. So why is it that the New York Times and the Washington Post have this story and the Washington Times does not? Here, I think a common sense answer would be the following: The looting is extremely embarrassing to the Bush administration, and it violates a basic promise that there would be peace created by the American forces in the brief transition to Iraqi rule. The explanation for this lacuna in the Washington Times could be innocuous: they ran out of space, they thought the story was unimportant. Or in fact, they don’t want to embarrass the Bush administration and so they play down this problem. This is for the historian to find out. Not by reading three newspapers but by seeing if this pattern endures over weeks and months. That’s the difference actually in a lot of ways between the historian and the journalist: we have the luxury of looking for months and years.Video Clip Transcripts:

2. How did you first get interested in newspapers from the French Revolution?

I was trained as a social historian, so instead of taking up texts that were written by smart people for smart people, I took up texts that were written by people who didn’t fancy themselves as intellectuals for the reading public. Well, the reading public was still pretty smart because it was very well educated. But still, I saw myself as being part of something called the social history of ideas, where you’re studying the ideas not of intellectuals, but of the middling classes. Then the notion of mentalité came in. Mentalité means what are the assumptions—the hidden assumptions even to the people of the time that frame their ideology. And I got really into using the press as a source for mentalité and these examples are trying to get at the underlying structure of what these people think. I was working on the revolutionary papers, which are propaganda, which have opinions. And so you’re presented with the opinions right away. You know who the authors are. But the real problem was that I still wasn’t interested in just another source to explain the ideology of Marat. That was already well known. What I was trying to get at was to get into the rhythm of the press, to let its own internal rhythms provide insight into how people thought about political things. What were their presuppositions? What was their mentalité? You can’t really call it ideology. You call it assumptions, to see what was the framing set of assumptions that they were working with. The second thing that I went after was, what did they think was an event? And how did they cover events? What I found was not surprising at one level, but surprising in another. These papers, which were, for the most part, propaganda journals, I mean they were “point-of-view” journals. I’m not saying that they just printed lies, but they definitely wouldn’t have printed something that was against their point of view. They still had 50 to 60 stories in a single issue. In other words, in a sense, it diluted the paper, their message. And I was very interested by the fact that they wouldn’t just cover the same incident over and over, driving home their point of view. Then the third thing I was interested in is how they covered individuals. In this environment, individuals only had two statuses: they were either heroes or villains. You’re with them, you’re a hero. You’re against them, you’re a villain.Video Clip Transcripts:

3. How do you read “between the lines” of a newspaper?

It’s very hard to make anything out of the 18th-century press, just as it would be if I just gave you the AP wire. There’s no background there. The most important thing you can find out from reading the papers is that you can’t go to them cold, unlike the modern paper. There is no periodical press in France until the early 17th century, and no really formalized one until the 1630s. The state realized that the press could be a problem from the beginning, and so they set up their own newspaper, the Gazette de France. They tried to have three newspapers, the Mercure, the Gazette and the Journal des Savants—Journal of the Intellectuals—and that would be it, that’s all they wanted. They didn’t want any independent press. But, with the technology of the time, France’s borders were a sieve. It was impossible to keep other papers out. And so, in fact, there’s two systems. There’s the state press and all around the state press are periodicals that are published in France but are censored. Or there are periodicals that are published beyond the borders of France that—they have licenses to get in and they can be revoked at any time. They’re directly controlled by the French government, that’s one set of papers. Then there’s domestic French papers that are under a lot of pressure. And then there are foreign papers that there’s a kind of negotiation. “If you don’t say this, we’ll let you in. If you go beyond that, we won’t.” Well this is a paper, the Courrier d’Avignon that I have here the Courrier of Avignon, that is kind of a mix between—this is a political newspaper—between the domestic papers and the foreign papers. It’s a mix because Avignon is not France, but it is entirely surrounded by France. Courrier d’Avignon is a little more independent because they can’t come in and smash the presses. On the other hand, the Courrier had to get along with them. This is from September 1770. A huge uproar was going on in France. The King was trying essentially to get control of his enemies, the parlementarians, the law court judges in Paris. And he was trying to really put clamps down on them. So that’s the lead story in the mind of everybody in France that picks up the Courrier d’Avignon. The first page and a half is on Venice. The next page and a half worth is on Rome. The next three-quarters of a page is on Genoa. Only when you get to the last page do you get to Paris, which is what most people in France bought this thing for. So in other words, they’re providing all sorts of innocuous news that’s not going to really bother the French all that much. “Ce sont les Vaisseaux le Dauphin & le L’Averdy arrives a l’Orient, l’un de Pontichery & l’autre de la Chine le 26 du mois dernier, qui ont apporte la Nouvelle de la rupture entre Hyder-Ali-Khan & les Anglois dans l’Inde.” “These are the vessels the Dauphin and the Averdy which arrived from the Orient, one from Pontichery and the other from China the 26th of last month which carried the news of the breakdown between the Hyder-Ali-Khan and the English in India.” It’s Parisian news alright, but it’s not going to shake the government. There actually are two small paragraphs, one sentence each, which concern the battle between the King and the Parliamentaire. Here’s what it says: “Les Chambres s’assemblerent Vendredi au matin, & M. M. les Gens du Roi leur avoit fait dire, qu’Elle ne vouloit ni recevoir, ni entendre ces Remontrances. Sur ce rapport la Cour remit la deliberation au Mardi 20 de ce mois, que les Chambres doivent se rassembler. ” “The chambers [of parlement] assembled Friday in the morning, & the King said to them that he doesn’t want to receive nor hear their complaints. On this report the Court postponed the deliberation until Tuesday the 20th of this month, and the chambers will reassemble after that.” This report comes from the 20th of August. So in other words, yeah, if you really know what’s going on already, you can learn something. But if you don’t, if you happen to be reading a newspaper because you wanted to find out about the controversy, you just know there is one. The only real reference to what it is, what’s going on, which historians could tell you all about, but I don’t know that contemporaries who read this paper could, is it’s on the affair of Monsieur le Duc d’Aiguillon. You have to know what that is.Video Clip Transcripts:

4. What can you learn about a society from newspapers?

There’s a bunch of things happening out there. No written source could ever cover them, no human being could comprehend them. What every paper has to do is sort out what it thinks is important and report that. That’s their basic job. The great majority of things fall onto the cutting room floor—not for ideology, not for point of view. But because no one can know them all. So when you come to a paper, what’s useful to know is as much as you can possibly know about what’s going on in that society through reading history books. So that you see what do they cover—what is strained out from the vast range of things. But that’s only a partial view because of many things that are happening. It’s not only that they don’t have time to cover them, they can’t think them. In the 18th century, they couldn’t think in terms of gender. They don’t have the category to work with. They have a sense of class, but not the Marxian sense of class. So they can’t think in those terms because no one is thinking in those terms. So the second thing you have to do is to take a number of contemporary sources and then you can see what the range of things that they can think about are. And then to see what this individual source does think about. They never talk about the role of God in winning a battle. Because they no longer—they’ve secularized—they no longer see the outcome of a battle as the direct hand of God. So that’s not in there. It’s also best to know what different contemporaries thought of the same thing because then you have a fair way of judging what they did. And you get that by reading other newspapers generally.Video Clip Transcripts:

5. What can you learn from newspaper advertisements?

What this paper is full of is ads for different things. And what I used it for is the same thing that people use ads right now for and that’s to get at the assumptions of society. What do people want to buy? So when you look at an ad for cigarettes or an ad for a car, you know the things that are emphasized are things that the advertisers believe will strike chords with the people who they hope will see them. And so, consequently, these are incredibly useful because you have people who have enormous incentive for knowing what are the basic assumptions of the society. They’re trying to pitch products that people want, and so they can tell you a lot about consumption. The vast majority are real estate. What I tried to do with these was I tried to basically bifurcate the ads into two categories. Are they trying to sell it as a piece of property that has certain inherent attributes? Or are they trying to sell it as a piece of property that actually had a certain history? In my mind, if it had a certain history—you know, so-and-so lived there, they made candles there, the past use of a building was what they were selling it for—that was a mindset that emphasized tradition. The 18th century is a watershed between understanding—having very traditional understanding of the economy—and believing in capitalism. A lot of these ads, more than half, and more and more as the century goes on, give you the dimensions, give you the physical attributes of the place, give you what you would need if you were going to put any business there, rather than the business that had been there. And this is also true for houses. The older ads tell you how the prior owner had it furnished. The newer ads tell you how many rooms there are and what the rooms were like.Video Clip Transcripts:

6. Who reads newspapers and how?

So the problem with the press is that you have an essentially anonymous writer and you have an unclear audience to you many times too. And unlike a book, which is meant to be read front to back, and many people read it that way, no one reads the newspaper that way. So you have to have a strategy. You have to imagine how someone actually has read this newspaper. You have to have a strategy that’s the generalized read. And then the other thing is that there are vast quantities of text. You could spend hours and hours if you said, “I want you to read every word.” No one does that. No one can do that. There are two ways that papers are read in 18th-century France. They are read in bookstores—people get subscriptions to reading rooms in the back of bookstores and they’ll find a whole slew of newspapers. And then a lot of people subscribe, they get their own. Papers are incredibly expensive. For example, the Courrier d’Avignon, I think, costs 35 or 40 pounds a year. The average artisan in this period is going to make 200 pounds a year. The people who read them from the artisanal classes are going to read them as hand-me-downs, as paper that was used to wrap something and then they read it again. Or they might have some access to a reading room. Unfortunately, to date, for 18th-century France, no one has really found a complete list of buyers for more than a couple of fugitive papers. What we generally have is a little information here and a little information there. And basically, that is, that’s as you’d expect for something that costs this much, the social elite dominates. And, in fact, at the top of the economic spectrum, nobles vastly over-represent themselves in terms of who buys these things. And then the next class would over-represent itself a little bit less. By the time you get down to the merchants, they under-represent themselves, even though they constitute an important part of the subscription list. Once you get beyond what French historians call the public, or you might call the literate elite, virtually no one buys these papers. One of the most interesting things about the press is the press is one of the first consumables. So they had to teach people to buy something that they were going to throw away. In other words, you have to eat, you have to have clothes. You know you’re going to throw them away when they’re threadbare, but most other items were bought forever. And so here they’re buying an item whose obsolescence is built into it and it takes a long time to convince people. So in fact, actually, we have a lot more copies of the press then anybody now would retain. People bound newspapers, you know, saved them, stuck them on shelves the way they would a book because, in fact, the whole notion of consumption is an 18th-century notion.Video Clip Transcripts:

7. How have newspapers changed over time?

This political newspaper is arranged as almost all political newspapers were arranged until the very tail end of the 18th century. It has a title, it has the date it was published. And then, what they do throughout, is they break it into stories that are the news from the point of view of different cities. So the first column is Venice and it has two stories that are from Venice but not necessarily about Venice. It’s what people in Venice think is interesting. Sometimes, you can see the same story pop up in different datelines, but you’ll see it from a different point of view. The most problematic part is there’s no headline and there’s no storyline embedded in it. It’s a nugget of information and it’s up to the reader to put it in. The huge change that occurs between the 18th century and the middle of the 19th century and on, is the arrival of headlines and the writing of the story so it could be sent out over a wire. So in fact, every story is, to, at least to a certain extent, self-contained. So that’s what’s fundamentally different. It’s not so much what’s there, but to the modern eye, what’s not there. And that’s the headline and the story. And the story is not encased. So you have to get into it. You have to dig out and ferret out what that story might mean. And it’s a big challenge to the historian.Download Full Video Transcript

Primary Sources

Credits

Jack Censer is Professor of History at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. Most recently, he published, with Lynn Hunt, a general study of the French Revolution entilted Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, which includes a book, CD-ROM, and website. He is also the author of The French Press in the Age of Enlightenment and Prelude to Power: The Parisian Radical Press, 1789-91 and of many articles on the history of French periodicals of the eighteenth century. He has edited two books: Press and Politics in Pre-Revolutionary France and French Revolution and Intellectual History. He has taught courses on the French Revolution, the social and cultural history of Europe, and the history of the family.

Grateful Acknowledgement is made to the following institutions and individuals for permission to publish material from their collections:

Musée de la Révolution française, Vizille (France).