Analyzing Religious Texts

Overview

The modules in Methods present case studies that demonstrate how scholars interpret different kinds of historical evidence in world history. In the video below, historian Sumaiya Hamdani analyzes a Hadith. Hadith are reports about what the Prophet Muhammad said or thought. They provide Muslims with a sense of how Muhammad applied the guidelines of the Koran to daily life. They are based on the memories and stories of those who knew the Prophet and were recorded a few generations after his death. Women in the Prophet’s family are acknowledged as legitimate authors of these religious texts, and they provide a glimpse into the roles that Muslim women played in the early Islamic period. You will be able to view primary sources from the Hadith in the menu below including a depiction of A’isha, one of Muhammad’s wives. She was close to the Prophet and is the author of roughly 1,200 Hadith. Her involvement tells us something about the public role that some women played in the early Muslim community and the respect she was given. The primary sources referenced in this module can be viewed in the Primary Sources folder below. Click on the images or text for more information about the source.

Video Clip Transcripts:

1. What are the Hadith and how are they connected to the Koran?

The Koran as a text is presumed to be the direct word of God transmitted through the angel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad and thereby to mankind. What the Koran says is not open to negotiation. Because Muslims consider it to be the direct word of God, it has a particular binding quality. However, the Koran does not address every facet of life. For that, Muslims go to the secondary source, which is the Hadith. And the Hadith are reports about what the Prophet did or said or thought or felt, reports, in other words, that help to give Muslims a sense of how the basic guidelines in the Koran were actually applied and lived by the Prophet himself. The Hadith were compiled a few generations after the Prophet’s death on the basis of what was remembered by the community and especially people who were connected to him at the time. They were considered canonical. There was a tremendous amount of discussion and of skepticism that surrounded scholars’ attempts to establish what were legitimate Hadith. A Hadith will begin with a chain of transmission—so and so was told by so and so, who was the wife of the Prophet, that he did this on this occasion. And then it will contain the actual report that could be anything from three sentences to three pages long. The Hadith are the testimony of individuals who are close to the Prophet, but who have often different recollections of what he might have said or done on any occasion. So what that leaves us with is texts and sources that reflect the accepted authority of women in the Prophet’s time and a variety of different perspectives on what might have happened in the early Muslim community. That women are acknowledged as authors of canonical religious texts is unique to Islam. At the time these Hadith were compiled, there was a lot of debate about what was considered acceptable or unacceptable material to put in these collections. Part of the debate revolved around whether or not women could even be considered authorities because by the 800s, Islamic society had expanded into much more patriarchal cultural zones. Fortunately, they hadn’t hardened to the point where even the women of the Prophet’s family were considered unreliable on the basis of their gender. That subsequent generations of women could make the same claims for the same kinds of authority is certainly not the case. The Hadith are very valuable because they give us snapshots of what life might have really been like. And on the important issue of gender relations, it tells us something about a very different kind of role that Muslim women played in the early Islamic period from what they’re presumed to play today. Where they’re clearly looked at as religious authorities, involved in the politics of the day.Video Clip Transcripts:

2. How did women come to be included in this religious tradition?

In the case of any religion, the formative period is always one of possibility and of change. Religions shake up social orders. They’re prescribing a very different vision, usually, than the status quo. Islam appeared and generated a certain amount of flux. In that flux, women were able to perhaps step out of more restrictive roles and exercise an influence that they might not have been allowed to exercise before. To a large extent, the reason that these women are included in the Hadith collection has to do with the circumstances of their being wives of the Prophet and/or companions of the Prophet’s family. Nevertheless, because they are women, their reports are going to be slightly different than that of men. And in some cases, their reports are going to be unique, because there are some things that the Prophet might have guided on or discussed with his wives and not with any other male member of the community. So they become oftentimes the sole sources of information on certain things that are particular to women. The women referred to as sources of information on the Prophet were naturally the women that were closest to him. Among them, his wives, A’isha in particular. The Prophet had a career that spanned two different phases. In the first phase of the prophet’s career, he was married to one woman, Khadija. When she died around 618, 619, the first woman that he married was A’isha, the very young daughter of one of his close companions, Abu Bakr. She was proposed to him as a suitable alliance, in part because of her personality, but also because of her relationship to Abu Bakr. The Prophet agreed to marry her, as he did many other women after her, by way of cementing alliances and rescuing some women from widowhood or other less than satisfactory social status. A’isha, however, in the second part of his life and career, was his favorite. She was close to him and close by him when very important things happen. She is used as a reference point for what the Prophet intended and how he applied Koranic prescriptions and guidance. Four to six standard collections of Hadith exist in Sunni Islam. In those, A’isha is the source or author of about 1,200 reports. What this tells us is that A’isha lived a very public life, because only as someone who had an obvious presence in the community would she be able to know about the Prophet’s experience or speak about the Prophet’s religious decisions, his legal advice. So not only is A’isha important because she constitutes the source for so many traditions in the collections of Hadith, but she’s also important because those traditions cover a variety of different topics. That tells us something about the very public role that women like her played in the early Muslim community and the respect that they were given despite their being women.Video Clip Transcripts:

3. What is the role of women in Islamic history?

Shortly after the Prophet’s death, the community expands and it ultimately becomes very vulnerable to local conditions and local attitudes. And one of the things that happens very rapidly and very noticeably in Islamic history is the marginalizing of women in Islamic society. When these early Muslims travel from Arabia to places like Spain or North Africa, to parts of the former Byzantine Empire or Persia, to places like India, what they encounter are misogynistic societies which have much more punishing attitudes about what the acceptable role of women is. Women, after the first few generations, disappear from not only religious literature but as actors on any other level. They are increasingly required to remain at home. They lose their knowledge of things that might make them authorities or sources of information. There’s this kind of tragic marginalization of women in the first centuries after Islam. Definitely the sort of public role that A’isha led and had, her involvement in politics, her involvement in war, her involvement in religion as a religious authority, her having led prayer. These are things that subsequent generations of Muslim women increasingly could not do. But there were other arenas where women became active, and as a result, have left us sources of information about what their lives were like. While women lost their role in the political arena and in religious authority, they did gain a presence in the world of literature. So you do have poetry, to some extent other kinds of literature, that are known to be authored by or presumed to be authored by women. They then become the window that we can use to get some sense of what women’s lives were like. A very different window, because such kinds of writing tends to be much more personal and reflective. And as a result, the kind of information you get is going to be different than the kind of information you get from Hadith, which speaks more to the public arena. The role of women in Islamic history is debated from two different perspectives. From the Western perspective, there’s a reliance on an accumulation of impressions and perceptions about Islam’s relationship to women. There is a premise that goes all the way back to the time of the Crusades in the 11th century that Islam is different from Christianity precisely because of the way women are treated. The debate from the Muslim perspective tends to be very defensive. Muslims will argue that the relative oppression of women in Islamic societies has less to do with the religion itself than it has to do with bad interpretations of its scriptures. And they will point out that the scriptures of Islam themselves are quite radical and revolutionary in lifting up the status of women. That’s how we end up with this debate that doesn’t seem to resolve itself. Neither side is taking into account the role of historical context. From the Western perspective, what the Koran says is not only understood the same way by all Muslims in all Muslim societies, but also applied the same way over time. There’s a tendency to essentialize Islam and turn it into a monolithic thing whereby one text determines the exact same behavior over time and across space. From the Muslim perspective, going back to the Koran and some of the early religious literature is an attempt to defend those texts against the Western critique. In doing so, they also engage in this essentializing discourse. As a result, we have two “freezeframe” approaches.Video Clip Transcripts:

4. How do we read Hadith by A’isha?

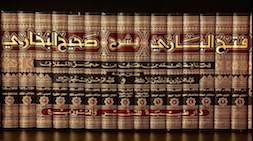

I brought some Hadith by A’isha that gives us a sense of not only the importance of her role but also, by extension, of the very different kind of life that women led in the early Muslim community. A’isha was often consulted on matters of what the Prophet had established as acceptable ritual practice, whether or not the Prophet outlined this or that kind of procedure for an important ritual. Even rituals as important as prayer are oftentimes confirmed by A’isha. In this particular Hadith, A’isha is asked to clarify something about praying and when it is acceptable to pray. A’isha narrates, “God’s apostle said and she quotes, ‘If any of you feels drowsy while praying he should go to bed till his slumber is over because in praying while drowsy one does not know whether one is asking for forgiveness or for a bad thing for oneself.’” Here you have an instance where A’isha is put a very simple question. Is my obligatory prayer to God acceptable if I’m in a state of drowsiness or does that render it null and void? She is able to quote the Prophet actually having pronounced on something similar in this particular tradition. She would become a reference or an authority for understanding acceptable ritual practice and in this case whether or not a prayer is acceptable or valid in the eyes of God. These are Hadiths that are recorded in the collection of Bukhari, one of the standard collections in Sunni Islam. In this one, A’isha remembers what happened at a very critical time, the Prophet’s death. That was a critical moment because the Prophet had not articulated, according to Sunni Islam, what was going to happen to the community and who was going to lead it before he died. Shiites argue that the Prophet had, in fact, selected his cousin and son-in-law, Ali, to be his successor. Sunnis argue that the Prophet had left no instructions, and therefore A’isha’s testimony is very important, because he died in her arms. So if there were any last minute instructions, they would have been given or issued while he was with her. The report, coming from A’isha has a certain authority in consolidating the Sunni argument. A’isha narrated: “When the ailment of the Prophet became aggravated and his disease severe, he asked his wives to permit him to be nursed or treated in my house. They gave him this permission. The Prophet then came to my house with the support of two men and his legs were dragging on the ground. “His legs were dragging on the ground between Abbas and another man. Ubaid-Ullah said, “I informed Abdullah bin Abbas of what A’isha said. Ibn Abbas said, “Do you know who was the other man?” I replied in the negative. Ibn Abbas said, “He was Ali.” A’isha further said, “When the Prophet came to my house and his sickness became aggravated he ordered us to pour seven skins full of water on him, so that he may give some advice to the people. So he was seated in a brass tub belonging to his other wife, Hafsa, when all of us started pouring water on him from the water skins until he beckoned us to stop and after that he went out to the people.”Video Clip Transcripts:

5. What can you learn from these Hadith?

Hadith are very complicated things to access, because they are reports coming from the 7th century. People had a very different way of communicating than we do. They involved a very intimate circle of people in the Prophet’s family and in the community. This particular incident is intimate because he’s dying. A’isha is talking about how the Prophet came to see her when he was very ill. There are clearly men present in the room. But, the question is whether or not the men included the person who would lend credence to the Shiite claim that the Prophet intended his cousin and son-in-law to rule. But men and women are clearly intermingling, even in the private space of the home. That tells us something about gender relations in the early Islamic community. In this very small paragraph you have an example of A’isha’s role in determining what was to be understood as the authoritative version, but at the same time, an element of dissonance or disagreement and possible contention by someone who’s embedded in that very tradition. The Hadith is something that you can approach and understand on a variety of different levels. You can read a very complicated Hadith like the Prophet’s last illness and understand from it the importance of the moment, the importance of A’isha’s presence, even if you don’t understand exactly what’s going on. In that Hadith on prayer, she’s a religious authority on the level of any other companion of the Prophet. Her proximity enables her to produce a verbatim quote of what he might have said. In the other Hadith, it’s clear that her proximity to the Prophet gives her a political authority that enables her to be used as a source on a very critical event.Video Clip Transcripts:

6. How do students understand the Hadith?

Students immediately understand the significance of including women as sources of information about religion. I think that’s not difficult to see from the Hadith collections and the traditions that are narrated on the authority of A’isha, but also of other women of the Prophet’s time. What’s a little bit more difficult to appreciate is the specificity of their roles, the reason that they are witness to certain events and what that says about their social roles. What’s interesting about teaching Islamic history or working on Islamic history is that the assumptions that students have about Islam—that women don’t have any rights, women lead very silent and oppressed lives. So when you’re confronted with a 7th-century text from the time of the beginnings of Islam itself, where a woman is pronouncing opinions on what might be the acceptable form of prayer or what might have happened the moment of the Prophet’s death, I think it’s not hard to appreciate that something is wrong with the picture that we usually carry around in our heads. To properly understand that kind of Hadith and use it as evidence or as a source of information, you need to be aware of the moment and you also need to research the individuals involved. And that may seem daunting, but many of the individuals that are involved are known about from biographical literature. So it’s a question then of cross-referencing that literature, of jotting down names either in the chain of transmission or in the actual report itself and researching them in the “who’s who” of early Muslims.Download Full Video Transcript

Primary Sources

Credits

Sumaiya Hamdani received her PhD at Princeton University and currently teaches history and Islamic studies at George Mason University. Her forthcoming book, Between Revolution and State: Qadi al Nu`man and the Construction of Fatimid Legitimacy, looks at revolutionary politics in medieval Islamic history.

Grateful Acknowledgement is made to the following institutions and individuals for permission to publish material from their collections:

The Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, www.cbl.ie