Margaret Mead, Coming of Age in Samoa

Annotation

In 1928, Martha Mead published Coming of Age in Samoa, an anthropological work based on field work she had conducted on female adolescents in Samoa. In Mead's book that became a best seller and unleashed a storm of controversy, she argued that it was cultural factors rather than biological forces that caused adolescents to experience emotional and psychological stress.

Mead's work had taken shape against a backdrop of broader anxieties about American youth generally and female adolescents specifically who were openly challenging social and sexual mores. Many contemporaries believed that the "storm and stress" of adolescence was biologically determined following a three-volume study of largely male adolescents by American psychologist G. Stanley Hall in 1904. Under the direction of her mentor, the anthropologist, Franz Boaz, Margaret Mead sought to study whether adolescence was a "period of mental and emotional distress for the growing girl as inevitably as teething is a period for the small baby? Can we think of adolescence as a time in the life history of every girl which carries with it symptoms of conflict and stress as surely as it implies a change in the girls' body."

In 1925, Mead observed, interviewed, and interacted with 68 girls between the ages of 9 and 20 living in three villages on the island of Ta‘ū in American Samoa. After 9 months of study, Mead concluded that unlike stressed American girls, the well-balanced and carefree nature of sexually-active Samoan girls was due to the cultural stability of their society free of conflicting values, expectations, and shameful taboos. Largely relieved of the baby-tending responsibilities that had burdened them as little girls, Samoan adolescents reveled in their freedom and deferred marriage during this "best period" in their lives.

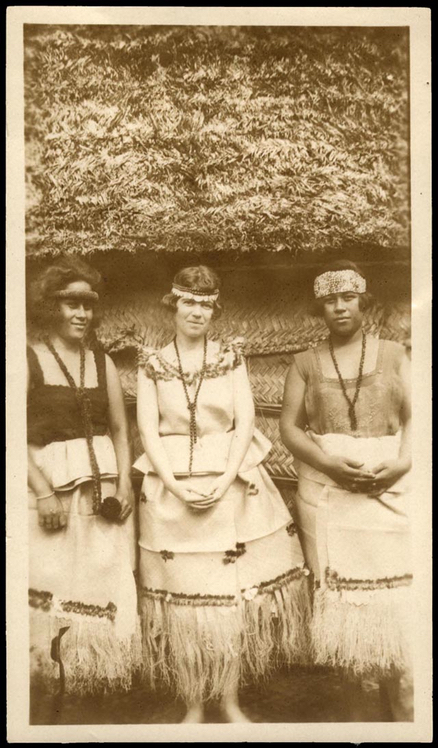

This is a photograph of Margaret Mead (center) and two Samoan adolescents. Mead donned a Samoan wedding dress woven by Makelita, the last Queen of Manu'a. (Mead's Samoan name was also Makelita). This photograph was one of three included in a letter to Ruth Benedict (dated February 10, 1926) in which she commented about her appearance, "I look very prim and proper and unpolynesian."

Text

Excerpt from Margaret Mead, Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilisation (New York: Morrow Quill, 1961), 195–96.

For many chapters we have followed the lives of Samoan girls, watched them change from babies to baby-tenders, learn to make the oven and weave fine mats, forsake the life of the gang to become more active members of the household, defer marriage through as many years of casual love-making as possible, finally marry and settle down to rearing children who will repeat the same cycle. As far as our material permitted, an experiment has been conducted to discover what the process of development was like in a society very different from our own. Because the length of human life and the complexity of our society did not permit us to make our experiment here, to choose a group of baby girls and bring them to maturity under conditions created for the experiment, it was necessary to go instead to another country where history had set the stage for us. There we found girl children passing through the same process of physical development through which our girls go, cutting their first teeth and losing them, cutting their second teeth, growing tall and ungainly, reaching puberty with their first menstruation, gradually reaching physical maturity, and becoming ready to produce the next generation. It was possible to say: Here are the proper conditions for an experiment; the developing girl is a constant factor in America and in Samoa; the civilisation of America and the civilisation of Samoa are different. In the course of development, the process of growth by which the girl baby becomes a grown woman, are the sudden and conspicuous bodily changes which take place at puberty accompanied by a development which is spasmodic, emotionally charged, and accompanied by an awakened religious sense, a flowering of idealism, a great desire for assertion of self against authority—or not? Is adolescence a period of mental and emotional distress for the growing girl as inevitably as teething is a period of misery for the small baby? Can we think of adolescence as a time in the life history of every girl child which carried with it symptoms of conflict and stress as surely as it implies a change in the girl’s body?

Following the Samoan girls through every aspect of their lives we have tried to answer this question, and we found throughout that we had to answer it in the negative. The adolescent girl in Samoa differed from her sister who had not reached puberty in one chief respect, that in the older girl certain bodily changes were present which were absent in the younger girl. There were no other great differences to set off the group passing through adolescence from the group which would become adolescent in two years or the group which had become adolescent two years before.

Credits

Image: "Margaret Mead standing between two Samoan girls," ca. 1926, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division (50a) (accessed October 23, 2009). Text: Margaret Mead, Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilisation (New York: Morrow Quill, 1961), 195–96. Annotated by Miriam Forman-Brunell.