Source Collection: Women and the Revolution

Overview

Women participated in virtually every aspect of the French Revolution, but their participation almost always proved controversial. Women's status in the family, society, and politics had long been a subject of polemics. In the eighteenth century, those who favored improving the status of women insisted primarily on women's right to an education (rather than on the right to vote, for instance, which few men enjoyed).

This source collection includes an informational essay and 58 primary sources.

Essay

Women participated in virtually every aspect of the French Revolution, but their participation almost always proved controversial. Women's status in the family, society, and politics had long been a subject of polemics. In the eighteenth century, those who favored improving the status of women insisted primarily on women's right to an education (rather than on the right to vote, for instance, which few men enjoyed). The writers of the Enlightenment most often took a traditional stance on "the women question"; they viewed women as biologically and therefore socially different from men, destined to play domestic roles inside the family rather than public, political ones. Among the many writers of the Enlightenment, Jean-Jacques Rousseau published the most influential works on the subject of women's role in society. In his book Emile, he described his vision of an ideal education for women. Women should take an active role in the family, Rousseau insisted, by breast-feeding and educating their children, but they should not venture to take active positions outside the home. Rousseau's writings on education electrified his audience, both male and female. He advocated greater independence and autonomy for male children and emphasized the importance of mothers in bringing up children. But many women objected to his insistence that women did not need serious intellectual preparation for life. Some women took their pleas for education into the press.

Before 1789 such ideas fell on deaf ears; the issue of women's rights, unlike the rights of Protestants, Jews, and blacks, did not lead to essay contests, official commissions, or Enlightenment-inspired clubs under the monarchy. In part, this lack of interest followed from the fact that women were not considered a persecuted group like Calvinists, Jews, or slaves.

Although women's property rights and financial independence met with many restrictions under French law and custom, most men and women agreed with Rousseau and other Enlightenment thinkers that women belonged in the private sphere of the home and therefore had no role to play in public affairs. Most of France's female population worked as peasants, shopkeepers, laundresses, and the like, yet women were defined primarily by their sex (and relationship in marriage) and not by their own occupations.

The question of women's rights thus trailed behind in the agitation for human rights in the eighteenth century. But like all the other questions of rights, it would get an enormous boost during the Revolution. When Louis XVI agreed to convoke a meeting of the Estates-General for May 1789 to discuss the financial problems of the country, he unleashed a torrent of public discussion. The Estates-General had not met since 1614, and its convocation heightened everyone's expectations for reform. The King invited the three estates—the clergy, the nobility, and the Third Estate (made up of everyone who was not a noble or a cleric)—to elect deputies through an elaborate, multilayered electoral process and to draw up lists of their grievances. At every stage of the electoral process, participants (mainly men but with a few females here and there at the parish level meetings) devoted considerable time and political negotiation to the composition of these lists of grievances. Since the King had not invited women to meet as women to draft their grievances or name delegates, a few took matters into their own hands and sent him petitions outlining their concerns. The modesty of most of these complaints and demands demonstrates the depth of the prejudice against women's separate political activity. Women could ask for better education and protection of their property rights, but even the most politically vociferous among them did not yet demand full civil and political rights.

After the fall of the Bastille on 14 July 1789, politics became the order of the day. The attack on the Bastille showed how popular political intervention could change the course of events. When the people of Paris rose up, armed themselves, and assaulted the royal fortress-prison in the center of Paris, they scuttled any royal or aristocratic plans to stop the Revolution in its tracks by arresting the deputies or closing the new National Assembly. In October 1789 the Revolution seemed to hang in the balance once again. In the midst of a continuing shortage of bread, rumors circulated that the royal guards at Versailles, the palace where the King and his family resided, had trampled on the revolutionary colors (red, white, and blue) and plotted counterrevolution. In response, a crowd of women in Paris gathered to march to Versailles to demand an accounting from the King. They trudged the twelve miles from Paris in the rain, arriving soaked and tired. At the end of the day and during the night, the women were joined by thousands of men who had marched from Paris to join them. The next day the crowd grew more turbulent and eventually broke into the royal apartments, killing two of the King's bodyguards. To prevent further bloodshed, the King agreed to move his family back to Paris.

Women's participation was not confined to rioting and demonstrating. Women began to attend meetings of political clubs, and both men and women soon agitated for the guarantee of women's rights. In July 1790 a leading intellectual and aristocrat, Marie-Jean Caritat, Marquis de Condorcet, published a newspaper article in support of full political rights for women. It caused a sensation. In it he argued that France's millions of women should enjoy equal political rights with men. A small band of proponents of women's rights soon took shape in the circles around Condorcet. They met in a group called the Cercle Social (social circle), which launched a campaign for women's rights in 1790–91. One of their most active members in the area of women's rights was the Dutch woman Etta Palm d'Aelders who denounced the prejudices against women that denied them equal rights in marriage and in education. In their newspapers and pamphlets, the Cercle Social, whose members later became ardent republicans, argued for a liberal divorce law and reforms in inheritance laws as well. Their associated political club set up a female section in March 1791 to work specifically on women's issues, including civil equality in the areas of divorce and property.

The boldest statement for women's political rights came from the pen of Marie Gouze (1748–93), who wrote under the pen name Olympe de Gouges. An aspiring playwright, Gouges bitterly attacked slavery and in September 1791 published the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, modeled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. Following the structure and language of the latter declaration, she showed how women had been excluded from its promises. Although her declaration did not garner widespread support, it did make her notorious. Like many of the other leading female activists, she eventually suffered persecution at the hands of the government; while Etta Palm d'Aelders and most of the others only had to endure arrest, however, Gouges went to the guillotine in 1793. Public political activism came at a high price.

Women never gained full political rights during the French Revolution; none of the national assemblies ever considered legislation granting political rights to women (they could neither vote nor hold office). Most deputies thought the very idea outlandish. This did not stop women from continuing to participate in unfolding events. Their participation took various forms: some demonstrated or even rioted over the price of food; some joined clubs organized by women; others took part in movements against the Revolution, ranging from individual acts of assassination to joining in the massive rebellion in the west of France against the revolutionary government. The most dramatic individual act of resistance to the Revolution was the assassination of the deputy Jean-Paul Marat by Charlotte Corday on 13 July 1793. Marat published a newspaper, The Friend of the People, that violently denounced anyone who opposed the direction of the Revolution; he called for the heads of aristocrats, hoarders, unsuccessful generals, and even moderate republicans, such as Condorcet, who supported the Revolution but resisted its tendency toward violence and intimidation. Corday gained entrance to Marat's dwelling and stabbed him in his bath. He often took baths for a skin condition.

Most women acted in more collective, less individually striking fashion. First and foremost, they endeavored to guarantee food for their families. Concern over the price of food led to riots in February 1792 and again in February 1793. In these disturbances, which often began at the door of shops, women usually played a prominent role, egging on their confederates to demand lower prices and to insist on confiscating goods and selling them at a "just" price.

A small but vocal minority of women activists set up their own political clubs. The best known of these was the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women established in Paris in May 1793. The members hoped to gain political education for themselves and a platform for expressing their views to the political authorities. The society did not endorse full political rights for women; it devoted its energies to advocating more stringent measures against hoarders and counterrevolutionaries and to proposing ways for women to participate in the war effort. Accounts of the meetings demonstrate the keen interest of women in political affairs, even when those accounts come from frankly hostile critics of the women's activities.

Male revolutionaries promptly rejected every call for equal rights for women. But their reactions in print and in speech show that these demands troubled their conception of the proper role for women. Now they had to explain themselves; rejection of women's rights was no longer automatic, in part because the revolutionary governments established divorce, with equal rights for women in suing for divorce, and granted girls equal rights to the inheritance of family property. In February 1791 one of the leading newspapers responded explicitly to Condorcet's article demanding equal political rights for women. The editor, Louis-Marie Prudhomme, restated the view, commonly attributed to Rousseau, that nature determined different but complementary roles for men and women. During the discussion of a new constitution in April 1793, the issue of women's rights came up once again. The spokesman for the constitutional committee restated the arguments against equal rights for women, but he admitted that deputies had begun to speak out in favor of women's rights. He cited in particular the pamphlet by Deputy Pierre Guyomar insisting that women should have the right to vote and hold office.

As the political situation grew more turbulent and dangerous in the fall of 1793, the revolutionary government became suspicious of the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women. The society had aligned itself with critics of the government who complained about the shortage of food. It also tried to intervene in individual cases of arrest and imprisonment. But the club did not readily give in to its opponents. One of its leaders, Claire Lacombe, published a pamphlet defending the club. Her pamphlet opens a window onto club activities.

Despite attempts to respond to the charges of its critics, the club ultimately fell victim to the disapproval and suspicion of the revolutionary government, which outlawed all women's clubs on 30 October 1793. The immediate excuse was a series of altercations between women's club members and market women over the proper revolutionary costume, but behind the decision lay much discomfort with the idea of women's active political involvement. On 3 November 1793, Olympe de Gouges, author of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, was put to death as a counterrevolutionary, condemned for having published a pamphlet suggesting that a popular referendum should decide the future government of the country, not the National Convention. Two weeks later, a city official, Pierre Gaspard Chaumette, denounced all political activity by women, warning them of the fate of Marie-Jeanne Roland and Gouges, two of several prominent women who went to the guillotine at this time. The Queen was executed on 16 October 1793, after a short but dramatic trial before the Revolutionary Tribunal. Roland, one of the leading political figures of 1792–93—she was the wife of a minister and hostess of one of Paris's most influential salons—went to her death on 8 November 1793, even though she was a convinced republican. Her crime was support for the "Girondins," the faction of constitutionalist deputies that included Condorcet.

After the suppression of women's clubs, ordinary women still had to make their way in a difficult political and economic climate. The Terror did not spare them, even though it was supposed to be directed against the enemies of the Revolution. A letter from a mother to her son illustrates the problems of provisioning and the haunting fear of arrest; the son of this woman was, as she feared, arrested as a "counterrevolutionary" (an increasingly vague term) and guillotined not long afterward. Many ordinary women went to prison as suspects for complaining about food shortages while waiting in line at shops, for making disrespectful remarks about the authorities, or for challenging local officials.

After the fall of Robespierre in July 1794, the National Convention eliminated price controls, and inflation and speculation soon resulted in long bread lines once again. The police gathered information every day about the state of discontent, and they worried in particular about the increasing shortages of February and March 1795. Women egged men on to attack the local and national authorities. These disturbances came to a head in the last major popular insurrections of the Revolution when bread rations dropped from one and a half pounds per person in March to one-eighth of a pound in April–May and rioting broke out. The first uprising took place 1–2 April 1795 (12–13 Germinal, Year III). A more extensive one broke out 20–23 May (1–4 Prairial). In both, women precipitated the action by urging men to join demonstrations to demand bread and changes in the national government. On 20 May a large crowd of women and men, armed with guns, pikes, and swords, rushed into the meeting place of the National Convention and chased the deputies from their benches. They killed one and cut off his head. As soon as the government gained control of the situation, it arrested many rioters, prohibited women from entering the galleries of its meeting place and from attending any kind of political assembly or even gathering in groups of more than five in the street.

Even as the fortunes of women's political activism were rising and falling, women began playing another kind of role, as symbols of revolutionary values. Most of the major revolutionary values—liberty, equality, fraternity, reason, the Republic, regeneration—were represented by female figures, usually in Roman dress (togas). The use of female figures from antiquity followed from standard iconographic practice: artists had long used symbols or icons derived from Classical Roman or Greek sources as a kind of textbook of artistic representation. French, like Latin, divided nouns by gender. Most qualities such as liberty, equality, and reason were taken to be feminine (La Liberté, L'Egalité, La Raison), so they seemed to require a feminine representation to make them concrete. This led to one of the great paradoxes of the French Revolution: though the male revolutionaries refused to grant women equal political rights, they put pictures of women on everything, from coins and bills and letterheads to even swords and playing cards. Women might appear in real-life stories of heroism, but they were much more likely to appear as symbols of something else.

Although women had not gained the right to vote or hold office (and indeed would not do so in France until 1944!), they had certainly made their presence known during the Revolution. At the end of the decade of revolution, a well-known writer, Constance Pipelet, offered her views on its impact on women. Although she stopped short of repeating Condorcet's or Olympe de Gouges's demands for absolutely equal rights for women, she did insist that the Revolution had forced women to become more aware of their status in society. She also argued that the Republic should justify itself by offering women more education and more opportunities. Her writing shows that women's demands had been heard and that even if they had gone underground, they had not been forgotten.

Women participated in the French Revolution in many ways: they demonstrated at crucial political moments, stood in interminable bread lines, made bandages for the war effort, visited their relatives in jail, supported their government-approved clergyman (or hid one of those who refused to take the loyalty oath), and wrote all manner of letters and petitions about government policies. As symbols, however, they did not appear in their normal guise in ordinary life at the end of the eighteenth century. To take but one example, an early allegorical painting by the artist Colinart of a woman dressed like a Roman goddess is a far cry from the actual mother of 1790 wearing ordinary clothes and depicted with her children in another painting.

Although no one has completed a statistical study of female figures in revolutionary art, even a cursory review shows many more depictions of women as allegorical figures than of women in their actual roles of the time. The most popular figure was Liberty, who became, in effect, the preferred symbol of the French Revolution. Called Marianne by her detractors to signal that she was nothing but a common woman (perhaps even a prostitute), Liberty nonetheless became indelibly associated with the French Revolution, so much so that she still appears prominently on French money and in patriotic paintings and statuary. Liberty usually appeared in Roman dress, often in a toga, holding a pike, the people's instrument for taking back their liberty, with a red liberty cap perched on its tip (the liberty cap too came from Roman times—it was supposedly worn by recently freed slaves).

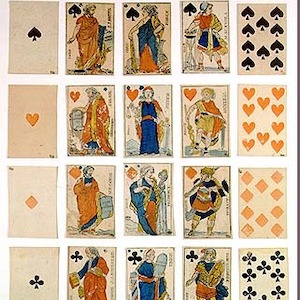

Liberty was often joined by another revolutionary virtue such as truth, as in the painting Allegory of Truth by Nicolas de Courteille. After the Republic was proclaimed in September 1792, depictions of the Republic as a female allegorical figure sometimes took over from Liberty. Liberty, Reason, Regeneration—as in this engraving of the Festival of Reunion of 10 August 1793 —Wisdom, and of course Equality and Fraternity, were all represented as women. These allegorical figures sprouted on every surface. Festivals featured them prominently, but so did the new republican calendar and the new revolutionary playing cards, which used Roman figures, both male and female, to replace the kings, queens, and jacks of old.

Why did women appear so frequently in these allegories and symbolic depictions? Why, for instance, does a giant female statue overshadow the scene in a painting by Lethière (Gillaume Guillon) showing a typical scene of registering for the draft. Although the picture is filled with ordinary people of the time, including many women, it emphasizes symbolically "the country in danger" through a gigantic female figure with her breasts exposed. The figure stands for "the country," which in French is a female noun (la patrie). As noted, it was iconographic tradition to depict virtues as female, but not as contemporary women. An artist signaled their symbolic status by dressing them in Roman or Greek garb or even by showing them half naked. No French woman would have dressed in this fashion, so no one would think that these women were real women. In Watch Yourself or You'll Be a Product for Sale, the depiction of contemporary women, albeit women dressing to please men, women are dressed in contemporary fashion; they are not shown as Roman or Greek goddesses.

Any educated person would therefore immediately recognize when a woman was an abstract quality or idea and when she was simply a woman of her times or a particular noted woman. Women made good symbols because they could not hold office or participate officially in politics. That is to say, it was impossible to confuse a depiction of "liberty" with any particular political leader or official, who was by definition male. The French were extremely worried that one man might take power and establish a dictatorship. They preferred symbols that could not be identified with any specific male political leader. Instead, Liberty became the dominant political figure. As a result, no individual ever enjoyed the symbolic status accorded George Washington, say, in the new United States.

Primary Sources

Credits

From LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY: EXPLORING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION, https://revolution.chnm.org/exhibits/show/liberty--equality--fraternity/women-and-the-revolution